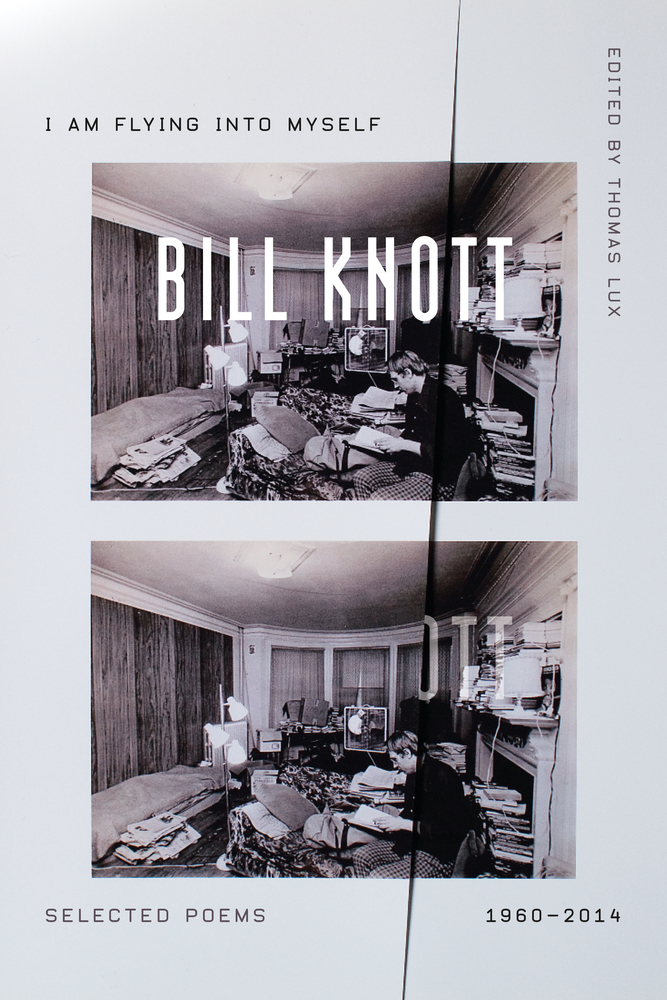

I Am Flying into Myself: Selected Poems, 1960–2014

by Bill Knott

reviewed by William Doreski

When Bill Knott arrived in the Boston area in 1968, he lived with Thomas Lux for a while, then rented an apartment in Somerville near the Everett Highway. He found it too noisy to work, so he boarded up the windows to muffle the traffic noise. In his chronically depressed way, he seemed happy in that darkened den without electricity or heat. Shutting out the world was one of Knott’s concerns in both life and in poetry. His surrealism distances the ordinary landscape of emotions, muffling his psychological self-insights in adventurous metaphors and sometimes placing something magical or bizarre between his speaker and whatever threatens to unravel him.

If I had a magic carpet

I’d keep it

Floating always

Right in front of me

Perpendicular, like a door.

(“Security”)

Reviewers have often had difficulty separating Knott’s poetry from the man; boarding up his windows is only one of many reasons why the actual Bill Knott can seem more an extension of his poems than the other way around. Because he recognized the danger of this misreading, he framed his first book by announcing the suicide of Bill Knott and attributing The Naomi Poems: Book One: Corpse and Beans to Saint Geraud (1940-1966). Saint Geraud was a character in a nineteenth-century French pornographic novel. It isn’t clear why Knott chose him as an alter ego, but the Naomi poems (and some of his later work as well) express a healthy, if sometimes skewed, sexual desire.

Although Knott later claimed that his purported suicide was in protest of the Vietnam War, the distinction it drew between self and speaker is important. The task of Knott’s poetry is to explore the self in a world of inadequate language. Because received language won’t suffice, Knott has to grapple with it in sometimes unprecedented ways. And because the self is too shy to be exposed to this process, he has to create another self to bear the brunt of his delving.

This is all to Knott’s advantage. Rejecting the confessionalism that hung over American poetry in the 1960s and 1970s, Knott turned to the surrealism and linguistic freedom of European poetry, as well as the figurative explorations of Hart Crane and Wallace Stevens and the musical experiments of Gerard Manley Hopkins. His nameless Everyman reports on an emotional life that only the most uninhibited psyche can express, as in the peculiar chiasmus of “Advice from the Experts”:

I lay down in the empty street and parked

My feet against the gutter’s curb while from

The building above a bunch of gawkers perched

Along its edges urged me don’t, don’t jump.

Knott is also adept at a kind of allegorical unreality common enough in European and Latin American poetry, but uncommon and usually ineffective in English-language poetry. Much American poetry of this kind succumbs to a lurking and subversive emotional imperative, but this is not the case with Knott’s “Itinerary”:

I pace off my heart,

six this way, six that way,

the length of a small wait

or a cave behind glass.Quenching my teeth in shouts

I advance little by little,

late by late.They open the door

emptier each time I pass,

they: the measured threshold,

the keyhole’s spider groin.Bury the dawn in ambush,

let white curtains count for home.

Make ruin my own.

If the basic move of poetry is to place one word next to another in a fresh and enlightening way, then this poem is a small masterpiece. Nearly every line contains an unexpected conjunction, slanting the imagery and situation to expose something new. In his most remarkable poems, like “Letter to a Landscape,” Knott complicates these glimpsed emotions in a dazzle of metaphor.

Knott became famous for brief poems somewhat in the manner of Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro,” but from the start he made even this haiku-like imagism his own, as in “Goodbye”:

If you are still alive when you read this,

close your eyes. I am

under their lids, growing black.

That he can extend this flash of raw sensibility into longer poems is astonishing. Poems like “Priscilla, or the Marvels of Engineering (A Fatal Fable),” “Overnight Freeze (Heptasyllabics),” and “Relic with Old Blue Medicine-Type Bottle: to X” maintain a disconcerting linguistic disorientation from beginning to end. But while Knott wrote many successful longer poems that exemplify his grasp of structure and compression, he frequently returned to the very short poem, as in “Alternate Fates”:

What if right in

the middle of a battle

across the battlefield the wind

blew thousands of

lottery tickets, what then?

Lux chose the poems for this edition from Knott’s own Collected Poems, which includes close to a thousand poems (yet excludes The Naomi Poems). He did a remarkable job; there’s not one clunker in this book, although everyone will prefer some poems to others. Every poet should be lucky enough to have his work edited with such care and discussed with such admiration. Thomas Lux, a good friend to Knott and many other poets, died on February 5, nine days before the publication date of this book.

Published on May 30, 2017