Hit Parade of Tears

by Izumi Suzuki, trans. Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, and Helen O’Horan

reviewed by Jenny Wu

After Japan’s surrender in World War II, Allied troops flooded the country, bringing with them Anglo-American sci-fi paperbacks. The genre, known as “Sf” in Japan, took off shortly thereafter with the emergence of the fanzine Uchujin in 1957 and the commercial magazine Hayakawa’s SF Magazine in 1959. During this time, Izumi Suzuki came of age in Shizuoka, Japan. A “Second Generation” Japanese Sf writer who hit her stride in the seventies, coinciding with the movement’s heyday, Suzuki left behind her a trove of short stories, plays, and novels when she died by suicide in 1986 at the age of thirty-six. Some of these stories are now available in English, published by a team of translators under the title Hit Parade of Tears.

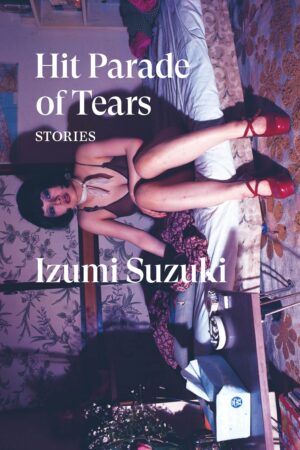

Suzuki’s biography is studded with intriguing relationships and collaborations that have tended to eclipse her work. She was married to jazz saxophonist Kaoru Abe and worked with the photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, whose edgy portraits of her collected in the tellingly titled IZUMI, this bad girl, are often used to market her writing. This is the case in Verso’s Hit Parade of Tears, whose violet-tinted cover features Suzuki seated on a rumpled, sinking mattress in red platform heels. The dark room from which the author stares out at her readers is disheveled, much like the eleven short stories in this new collection. Here, as in Suzuki’s prose, the bedroom is laid bare: no longer an insular personal space, it becomes a microcosm of the social sphere.

Hit Parade of Tears embodies 1970s Japanese counterculture and its youth, labor, and gender politics through depictions of alien visitations, anti-aging bodies, witchcraft, and heart-stopping acts of violence. Scholar Takayuki Tatsumi credits Suzuki with inventing an “Sf of manners,” a designation that links the Japanese author to literary greats such as Jane Austen and Honoré de Balzac, whose fictional worlds mirror the social stratification of real life. The novel of manners is a genre in which women’s lives play a significant role. However, Suzuki and her female contemporaries during the Japanese Sf boom were mostly sidelined and explicitly excluded from all-male writers’ associations. Suzuki famously observed that her male contemporaries’ work revealed their unforgivable failure to understand what was wrong with society. Meanwhile Suzuki depicted “feminine” subjectivity in a daringly idiosyncratic way that, although flawed when judged by today’s standards, pushed back against the dominant attitudes of her time.

Suzuki’s female characters get to be depressed, bitter, and even passive. Her story “Memory of Water” follows a woman who has trouble getting out of bed and her wild alter ego, a coping mechanism that switches on whenever she buckles under social pressure. Suzuki’s characters can turn from innocent high schoolers into cold-blooded murderesses. The collection’s strongest story, “The Covenant,” starts from a simple premise: some individuals believe they can telepathically communicate with aliens. When this ability manifests in men, it causes them to pontificate late into the night. But when a seventeen-year-old girl named Akiko with this talent begins to believe that the aliens have asked her to “shed Earthling blood,” she and her misfit friend Nana lure a middle-aged mark to a bar where unthinkable acts ensue.

The 2021 translation of Suzuki’s story collection Terminal Boredom drew comparisons to Ursula K. Le Guin, Philip K. Dick, and Anna Kavan. Walking a fine line between sci-fi and psychedelic mundanity, Hit Parade of Tears contains shorter, fable-like tales such as “The Walker,” in which the trade of a silver ring for a bowl of udon leads to a senseless death. These possess the cryptic quality of Yasunari Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories, whose abrupt endings often leave readers with a feeling of justice gone awry.

Suzuki’s shorter stories can be perplexing and lie at the weaker end of the collection. Those stories dealing with mental illness, particularly schizophrenia, and mental asylums are more fleshed out. These stories show the influence of Kawabata’s posthumously published, unfinished novel Dandelions. In Suzuki’s story “Full of Malice,” a woman visits a psychiatric ward in search of her younger brother, only to find that the patients in the facility have been lobotomized, her brother “encased in glass, his belly ripped open.”

While Kawabata is concerned with abnormal psychology, in Suzuki’s work, the shady dealings of the mental hospital are the focus. For Suzuki, individual pathology is a symptom of larger structures of oppression. Her characters’ clever means of dealing with society give life to each story even half a century after their original publication. It is not so much the specifics of the worlds Suzuki creates as the way her characters find relief within them that makes Hit Parade of Tears translate well for a contemporary audience.

Published on June 13, 2023