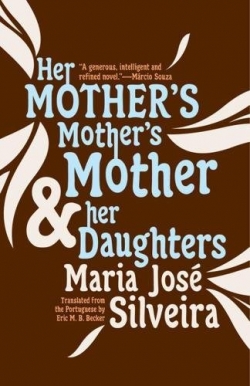

Her Mother’s Mother’s Mother and Her Daughters

by Maria José Silveira, translated by Eric M. B. Becker

reviewed by L.E. Goldstein

Her Mother’s Mother’s Mother and Her Daughters traces a Brazilian family’s lineage from the arrival of the Portuguese armada in 1500 to the twenty-first century. A seemingly omniscient narrator tells the stories of her ancestors, focusing, as the title suggests, on the women of the family line. These women are wide-ranging and complex. They vary from medicine women to artists to slaves to cattle farmers to poets and politicians; they are lovers, peacemakers, healers, materialists, and murderesses; they are indigenous, West African, Portuguese, Spanish, French and a mix of all of these. The variety of their personalities, and the pain, beauty, and strength they display shows that genetics alone does not make a person who they are. In this book, the characters’ environments form them, from the people with whom they interact to the great changes taking place in the pulsing heart of Brazil itself.

The original Portuguese version of Her Mother’s Mother’s Mother and Her Daughters was published in Brazil in 2002. This was Silveira’s debut novel, and she has published six further books and three plays since then. Like Ligía, one of the women in the book, Silveira’s life was affected by the military dictatorship in Brazil. She and her husband were forced to go into hiding after being accused of “subversive activities” before finally being exiled to Peru. She returned to Brazil in 1976 and now lives in São Paulo.

While the author’s personal story is part of the recent history of Brazil, she also accurately portrays centuries of historical facts and events through her well-developed characters. Tied closely to the historical narrative is Brazil’s racial narrative, which has an effect on every generation. The first character to become a slave, the indigenous woman Sahy, dreams about a jaguar who has been captured and lost its strength and beauty, only to later discover she is the jaguar of her dream as she falls into her captor’s nets. Things unfold before her as if they aren’t happening to her: “She moved past the anger that she sensed would do no good and the sorrow that she knew to be useless, and soon reached a stage in which she always reached beyond, the stage where she could accept and contemplate the world as a passive observer of the infinite human capacity to inflict suffering.” The novel’s treatment of race is reminiscent of Edwidge Danticat’s The Farming of Bones, which takes place in racially and politically tense Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Like Danticat, Silveira successfully injects individual narratives into major historical events, creating a satisfying environment for both the history buff and the character analyst.

Translator Eric M. B. Becker, the winner of a 2014 PEN/Heim Translation grant, produces an excellent translation. By leaving particularly Brazilian terms such as “emboaba” and “cafuzo” untranslated, Becker manages to make readers of English understand the untranslatable within its context. The novel maintains a casual, dreamlike quality, as if the narrator were telling these stories to a friend. Each character is given their own original voice, emotions, and musicality. If some syntax feels unexpected, it is almost always for the benefit of sound.

Her Mother’s Mother’s Mother and Her Daughters offers a multitude of distinct journeys, despite the fact that all of the characters are from one family line, representing only a small piece of Brazil’s five-hundred-year history. Each woman’s life adds a unique perspective to this history, broadening its range one story at a time. The overarching sense of sadness and loss throughout the book is rivaled by just as much strength and resilience from its characters. As the narrator puts it:

There have always been all kinds of men and women, weak and strong, craven and gullible, intelligent and limited, good and bad, powerful and impotent. But you all can be certain of one thing: the women who lived in the vast, unforgiving, magnificent backlands in the early centuries of this country’s history could be many things—but silly and fragile they were not.

Published on February 27, 2018