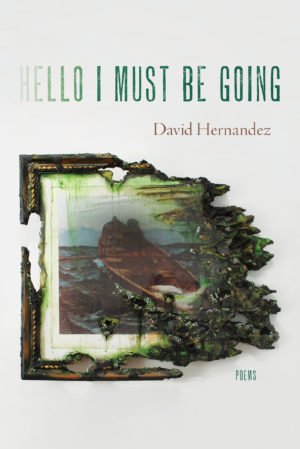

Hello I Must Be Going

by David Hernandez

reviewed by Adam Scheffler

David Hernandez arranges his fifth poetry collection, Hello I Must Be Going, as a kind of three-part exhibit. And, like any good exhibit, we feel the care of its curator in its conception and arrangement. The book’s first section takes its titles from the “word paintings” of artist Ed Ruscha, riffing off of them in surprising ways (for instance, a painting entitled “It’s Only Vanishing Cream” becomes a poem about a family member’s two close calls with death). The book’s second section, “The Silent Docent,” offers us a series of poems that approach crises (such as COVID and police violence) elliptically by “look[ing] closely” and “closer still” at a series of described landscape paintings. The third section closes out the book with four poems about artists—Jean-Michel Basquiat, Ai Weiwei, Marina Abramović, and Raphael—whom Hernandez admires and to whom he turns for solace and inspiration.

In arranging his book this way, Hernandez demonstrates how some art helps us bear the world while also making us face its full menace and brutality. For Hernandez’s poem-gallery is frightening—full of death, sick loved ones, and dire social problems such as climate change, active shooters, and Trump’s abuse of migrant children. The book asks us to pay anguished attention to these threats and disasters, but offers art, and the ways we attend to art, as an intermediary between us and brute reality. In reading the book, we become the active museumgoer who must respond carefully and creatively to fraught canvases. The book is full of careful acts of looking and noticing: in “Landscape with Protestors,” Hernandez asks what “that black butterfly shape” is and answers, “You only have to / close the space between you / and the canvas to see.” Or, examining the painted figure of Herodotus in Raphael’s The School of Athens, Hernandez describes in detail the philosopher’s

[ … ] lilac-colored

stonecutter’s smock, his tan

workmen’s boots.And the marble block

where he rests his elbow [ … ]And all the shadows

woven over him, encroaching toward

what is lit.

This kind of scrupulous aesthetic attention leads us not away from history and mortality but toward them: the “butterfly shape” turns out to be the sneakers of a person killed by the police, and the woven shadows encroaching on Herodotus, it’s implied, will eventually swallow him and us both. But by directing our attention to these dire subjects as depicted in artworks, these poems stir our imagination and invite us to be more generous and humane in our responses (in a manner that “doomscrolling” breaking news on the Internet perhaps does not). For instance, in the COVID-era poem, “Landscape with a Doctor Taking a Breather,” the titular doctor sits on a green hill while a palomino’s “sideswept / white mane” suggests that it’s a windy day in the painting. When the poem imagines how “good” that wind “must feel” against the doctor’s “unmasked face,” we are left to picture the grim, death-filled hours in the hospital that make this pastoral setting such a relief.

Indeed, Hernandez’s “silent docent” doesn’t “tell [us] / what it all means,” but instead insists that careful, compassionate looking is a good that art can both incite and offer, an idea demonstrated through his poem “Marina Abramović’s Gaze.” In her famous performance piece “The Artist is Present,” Marina Abramović sat opposite one spectator at a time for hundreds of hours in total, making steady eye contact and frequently moving her spectators to tears. Hernandez’s speaker imagines Abramović sitting opposite him in his kitchen at 2 a.m., offering him her “distilled // empathy.” He describes her gaze as the “softest of shovels, a tender / excavation to see the why of my sleeplessness,” as she then imagines his trip to the doctor with his wife, and his act of tenderly shaving his sick wife’s head.

Abramović here cannot physically help, but she offers a kind of witnessing and support. It mirrors an earlier poem in the collection, in which a speaker looks on a landscape painting of fleeing migrant figures and wishes to “help them find whatever they need [ … ] / the sparkling blue stream/ you dream up for them.” And Hernandez explores various other boons that visual art can offer beyond heightening compassion: for him, it offers wild gestures and stylish shows of defiance (“Basquiat’s Bones” and “Ai Weiwei’s Middle Finger”), encourages the ferocious appreciation of what will soon disappear (“Still Life”), gives us starting points for engagement (Ed Ruscha), and much else. Again and again, Hernandez turns to visual art to help him bear up and stay attuned and awake, a kind of support that he offers us, in turn, through his poems.

Yet looking at others suffering and merely wishing to help is not good enough, and such attunement should not make us comfortable (just ask Abramović, sitting for hundreds of hours in her chair). Hernandez’s poems remind us of this, and suggest as well that aesthetic attention can be deeply unsettling. In one poem, a painting of a wildfire (induced by climate change) itself ignites, “drips and blisters” while “we step back,” seeking a “seemingly safe” world outside that of the gallery. In another poem, looking at a painting makes Hernandez’s speaker think vertiginously of the Milky Way, hurtling at “1.3 million mph” through “dark, soundless space.” We’re not meant to feel safe in these poems, but at least we’re facing that “spiraling” “velocity” with and through the poet, his heart “going pretty fast now.” “Here, place your palm against it,” he invites us, “Over my sticker that says Visitor.”

Published on October 18, 2022