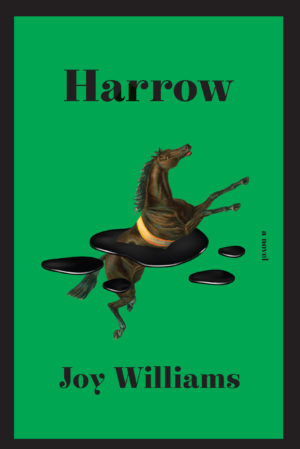

Harrow

by Joy Williams

reviewed by Jane Balkoski

The Quick and the Dead, Joy Williams’s 2000 novel, takes place somewhere in the hostile Southwest; Arizona, perhaps. A town, perhaps, but the various buildings in which the action unfolds—a sleek mansion, a nursing home, a wildlife museum—seem to float in the desert, each one as opaque as a dream. Three motherless teenagers wander from scene to scene, meeting peculiar adults along the way. This is my world, the reader thinks, when the main character launches into a screed against agribusiness. This may not be my world at all, she thinks, several pages later, when she reads, “One listens in vain … for anything extraordinary in Schumann’s last works. They are simply weak!”

Harrow picks up where The Quick and the Dead left off, in a world both like and unlike our own. Precocious teenagers—in this case, Khristen, our narrator—take note of their parents’ failings and reckless ways. When her parents’ marriage falls apart, Khristen winds up at a boarding school whose teachers make inscrutable utterances. “Most schools told their captives many things without teaching them anything, filling them not with wisdom but the conceit of wisdom. [ … ] Things would be different here.” Then a cataclysm shakes the outside world and Khristen begins to pick her way through the wreckage, ostensibly in search of her mother. So ends Book One.

Things become increasingly abstract in Book Two, as Khristen leads us into the future and Williams swaps out the first person for the third. For an indefinite period, eternity perhaps, Khristen sojourns at a former resort, now “suicide academy,” by a former lake, now toxic slurry. The elderly guests are planning elaborate acts of violence in the hopes of saving an unsavable world. Each guest has a unique target: an herbicide representative, the US Navy, a scientist who experimented on animals.

Our delight in the collapse of the plant and animal kingdoms. Our insatiable appetites. Williams has studied man’s cruelty from different angles for decades now. In her own words, Ill Nature, a collection of essays and fragments published in 2001, is meant “to annoy and trouble and polarize” with its flat and brash style. Williams rails against weak-willed conservationists and money-hungry lobbyists alike. In The Quick and the Dead, she gives her own tirades to the unpopular protagonist, Alice. When a friend offers a glass of lemonade, Alice says: “You are aware, are you not [ … ] that American sugar is destroying the Everglades? Big Sugar is a wealthy government-sponsored ecoterrorist that pollutes thousands of acres of one of the most remarkable ecosystems on the planet.” Her friend rolls her eyes; Williams smirks at her own convictions.

If The Quick and the Dead ironizes Ill Nature, Harrow charts a different course. Where are we going? The reader may wonder, alarmed, as the plot, like a coastline, recedes from view. Williams reverts to the first person in Book Three, but Khristen is transfigured, divested of her personality. She is now a pilgrim, a witness, and Harrow an allegory. Nature has finally been vanquished—an unnamed youth tries to cut down the last living tree with a file. A child-judge presides over humanity, or perhaps the afterlife, issuing enigmatic sentences. Even night has been abolished: “Outside, massive lights were triggered, splashing his chambers with glare. Each dusk they made it official that night was no longer permitted. Erebus be gone!”

Williams conceals much in this final section, but she gives the reader a hint: consult Kafka! She refers to his relatively obscure story “The Hunter Gracchus” again and again throughout the final pages. Readers who take her suggestion may puzzle over the tale of a hunter whose death ship takes a wrong turn on the way to the underworld. Perhaps Khristen, like Gracchus, is stranded between life and death. Perhaps Khristen links the present to the hopeless and hideous future.

And what of the titular harrow? It only shows up a few times, an emblem of the post-apocalyptic world. “Representations of the harrow are in all government facilities that remain and homes are encouraged to display the image as well. It started out as a bit of nostalgia but devolved into a sign of respect, of self-acknowledgment. No one gives thanks to it of course, just respect. It’s a unifying symbol.” The diligent reader once again consults Kafka. In one of his best-known stories, “In the Penal Colony,” the harrow is an instrument of torture that carves the law the prisoner has broken into his back, letter by letter. To understand his crime, the prisoner must decipher the harrow’s movement along his skin. The harrow operates continuously for 12 hours, adding decorative flourishes to the text till the prisoner dies and drops into a pit.

The reader of Harrow, like the prisoner, looks for meaning. The novel elaborates on its own images, ceaselessly, until it ends in “roaring, engulfing dark.”

Published on October 26, 2021