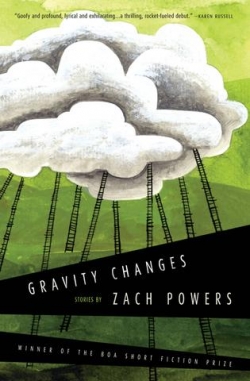

Gravity Changes

by Zach Powers

reviewed by Chelsea Bingham

The nineteen stories in Zach Powers’s debut collection, Gravity Changes, cover topics as ordinary as childhood and as extraordinary as a man marrying a light bulb. Characters as diverse as the devil, number-punching coworkers, and ancient haruspex (one who divines the gods’ intentions by reading animal entrails) make this a varied and inventive read.

Some story titles are tiny masterpieces in themselves, most notably “a tinkle is the sound of two things meeting but failing to merge,” sounding like a Zen koan; “Joan Plays Power Ballads with Slightly Revised Lyrics,” a Borges-esque creation; “One Has Hugs the Other Punches,” narrated by a grandmother about her marriage to the devil; and, of course, “Cockpuncher,” which speaks for itself. As successful as many of these titles are, some of the stories don’t live up to them. Occasionally too self-aware, the prose can be heavy-handed, hitting you over the head with ideas that would flourish if given the room to breathe. However, Powers can write. Some of the more successful and engaging instances follow.

In “Gravity Changes,” the first and title story, a young boy narrates his childhood through the gravity-bending activities in which he and his friends engage. “When I was a boy we walked on walls. The kids these days climb trees like it’s some sort of accomplishment.” While on the wall, the boy “drops” a ball to his friend standing on a wall across the street from him. His friend drops the ball right back. When a friend passes by on the street below, he drops the ball, and his friend drops it back to him atop the wall. Then wall-walking turns to flying: “Was it rightly flying? I don’t think so, not by the standards we have today, when flying is a fight against the concept of down, but we didn’t have that concept back then.” Broken arms, knocked-out teeth, bruises, and scrapes sustain the boy and his friends through the summer, but with the start of school, “routine pressed down upon us, and soon enough we were walking like everyone else.” Gravity here acts as the equivalent of taking a bite of the apple, as paradise gives way to reality.

The stakes are increased in “The Tunnels They Dig” as the narrator, an astronaut who has abandoned ship, says, “I am not floating. I am falling. Below me is the sky. I am falling toward the sky.” The concepts of below and down, inconceivable to the children in the title story, are now fully formed and set in space. The narrator continues, “I am falling toward myself,” elevating this awareness to consciousness itself. Perhaps a little too profound and precious a pronouncement, Powers here provides a counterbalance: the astronaut’s companion on the shuttle, a scientist, was “studying worms and the tunnels they dig when weightless. When falling.” As the narrator floats in space contemplating the thin layer of air in his space suit separating him from the cold and radiation surrounding him, he takes a floating worm into his hand. They fall toward Earth together, calling to mind the phrase “worm-food,” a morbidly satisfying conclusion.

“Sleeping Bears” takes gravity and it applies it to what people do and say. In this story, your innermost thoughts and secrets have serious consequences, as they are broadcast across your forehead. Whether it’s “FUCKED NORMAN FROM ACCOUNTING” or “AWKWARD AT STARTING CONVERSATIONS,” you learn things about your coworkers, bartenders, and people on the street that you would rather not. Like most things in life, this skill can be manipulated, though few realize it. The narrator learns to channel his thoughts and emotions until he “tried to will a message to form, but there was nothing left to say.” What you display has more to do with the way you see yourself and the world around you than objective fact. Social media users take note.

All of these stories contain elements of mindfulness and meditation. Whether it’s the children realizing that their imagination has limits, the astronaut contemplating his grave, or the man who learns to clear his mind (and forehead) of all unwanted confessions, these characters are on a path of discovery. “Unlearn to Seek” offers one sentence that might encapsulate this collection: “The whole is broken into its components and reassembled, and this reassembly is called finding.” These stories—offering narratives that are broken and reassembled, often in surprising and occasionally thought-provoking ways—consistently provide an interesting lens through which to examine and reexamine habituated patterns of thinking, particularly about oneself.

Published on October 27, 2017