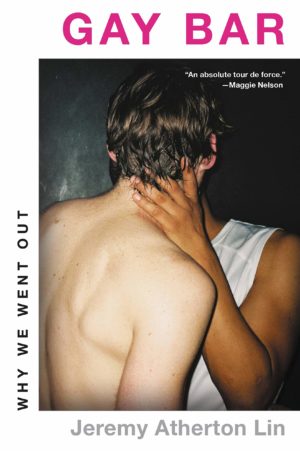

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out

by Jeremy Atherton Lin

reviewed by Richard Scott Larson

Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Gay Bar: Why We Went Out is a seamless combination of memoir and cultural history, orbiting the yesteryear of queer nightlife—a captivating exercise that hinges on the limitations of one genre proving the necessity of the other. The occasion for Atherton Lin’s shamelessly hybrid text is the realization that, just as queerness has graduated into the mainstream, and cruising now primarily exists in the digital sphere, so too has our quintessential gathering space—the gay bar—lost something of its urgency. “Gay is an identity of longing,” Atherton Lin writes, as he looks back on years spent in those dark, crowded places, “and there is a wistfulness to beholding it in the form of a building, like how the sight of a theater stirs the imagination.” But what does it mean to the identity itself, he wonders, when the spaces that once defined it have begun to disappear? In this way, the book serves as both memorial and testament.

An epigraph from filmmaker and writer Derek Jarman, a major figure in gay rights activism at the height of the AIDS crisis, opens one chapter: “When I was young the absence of the past was a terror. That’s why I wrote autobiography.” The real histories of marginalized communities have often been made difficult to access, and Jarman sought to leave behind a record of his own life as a way of self-consciously contributing to the archive. Similarly, the act of remembering the way things once were becomes in Gay Bar a radical necessity—and a reminder that history, after all, is a privilege.

Having come out after the emergence of AZT, Atherton Lin acknowledges that he was once repelled by what the gay past represented. But as a writer now compelled to recount that history, and asserting the value of his own personal experience, he doesn’t shy away from the darker elements of his subject. AIDS, police brutality, a history of racism and violence—the gay bar doesn’t get off easy just for being a sometimes lifesaving haven for a privileged few. Its white cisgendered chronicler here acknowledges his own complicity in its history of exclusion. At the same time, he also revels delightfully in what amounts to an archive of sensory experience: neon lights and roaring pop music and the unmistakable smell of cock in a crowded room full of men. He describes his early experiences as a gay man in gay places with a tenderness for his younger self that never quite veers into sentimentality, presenting instead a hyper-contextualized nostalgia with well-curated dips into the historical record.

The gay bar I’d once escaped to as a teenager, armed with a fake ID and the need to outrun the stranglehold of the closet, is now a ruin. A friend from adolescence recently texted me a video of what it looks like now, and at first I didn’t recognize it as the refuge it had been. A shaky camera moves through the darkness; it catches glimpses of wood scraps and cinderblocks haphazardly piled up, trash strewn everywhere. A TV appears, cracked open and lying on its side, which I remember had once hung high up on the wall, always playing vintage pornography. For me at the time, the bar was aspirational, representative of a future I wanted for myself outside of the closet. But as Atherton Lin also recalls wondering, when perusing zines from the same era, it’s likely that the actors in those old videos I was watching were already dead.

Atherton Lin writes about gay culture as having been built on the idea of imitation, “the longing embedded in feeling real—on embracing that feeling, and refusing to accept realness as it’s been constructed for us.” And if the gay bar was once a place where we hoped we could find ourselves—to be someone different from who we’d been before—we did so with intention, building an identity from the ground up, playing the part until we’d memorized every line. Now these empty gay bars are “cast-off exoskeletons,” representative not of the promise of our future selves but of a time that has come and gone. And the gay bars in the larger city where I live now are often overrun by straight tourists and drunken bachelorette parties, appropriation being a natural consequence of being seen.

As these remaining partiers can attest, gay bars obviously still exist—“this is what we fought for, apparently”—but Atherton Lin makes the case for why they’ll never be the same. And in his delicate retelling of his own late nights, we come to recognize both the quaintness of ghettoization and mixed feelings about its transience, as well as the more intimate story of a youth spent in a lost time and place. “There are nights that have an audible pulse,” he writes, just before quoting some rapturous lines from Verlaine by way of explaining the dopamine tether drawing us out into the crowds, “so we dance.” But upon reaching the wistfully moving conclusion of Gay Bar, its narrator—a historian-as-participant—heads out of the bars and into the streets. This time, however, he’s on his way home.

Published on June 1, 2021