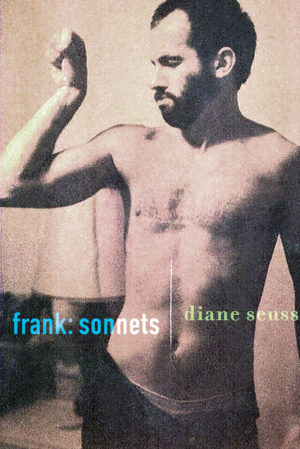

frank: sonnets

by Diane Seuss

reviewed by Thomas Mahon

In this dynamic and deeply original collection of poems, her fifth to date, Diane Seuss sets off on a “restless search for beauty or relief.” Nothing seems off the table: the poet’s childhood in small-town America, her father’s early death, her mother whose “domain was TV dinners and James Joyce,” the loss of close friends to the 1980s AIDS epidemic, chance encounters with strangers, artists, lovers: these are all key players in this poet’s quest. In these pages, Seuss, a recent Guggenheim fellow and an already accomplished American poet, adopts the sonnet as her form of choice. The sonnet, which originated in thirteenth-century Italy, entered English poetry in the sixteenth century through the poems of Sir Thomas Wyatt. Since then, poets from William Shakespeare to Pablo Neruda have turned to this resilient and endlessly evolving form. As Seuss sees it, “the sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do / without. To have, as my mother says, a wish in one hand / and shit in another.” Through the limited space of the sonnet, Seuss’s work is to extract meaning from life’s vast brokenness and chaos.

Within each poem in this book, the poet urgently searches for “a nonfussy definition / of the Sublime.” Often, this means seeking meaning in human suffering. The poet unflinchingly paints a portrait of an HIV-positive friend, “covered in KS lesions,” of a son who has just overdosed, and of a world where “the membrane / between life and death will thin like the effacement / of the cervix.” In the poetry of John Keats, “mortality / Weighs heavily on me like an unwilling sleep,” but in Seuss’s sonnets, mortality is at times like a membrane: thin, light, self-effacing. Of caring for her son after his overdose, the poet writes, “I am in no way Jesus, I am in no way even the bad Mary / let alone the good, though I have held my living son / in the pietà pose, I didn’t know at the time I was doing it.”

Seuss is at her most moving and morally attuned when she experiences this membrane of mortality opening and reckons with the thinness of life. Of a friend dying of AIDS, she writes, “for a moment / I knew what it would be to feel at the mercy of love, small-scale, the kind shown but not / spoken of. I was afraid to touch you. I was afraid of the lesions you’d described to me … ‘Jesus-marks,’ / you called them.” Here, “I was afraid to touch you” is an immediate, real-world fear of touching this friend’s delicate skin. It is also an echo of Jesus’ admonition to Mary Magdalene, “touch me not for I am not yet ascended to my Father” (John 20:17). Seuss’s poems depicting friends suffering from AIDS are among the most memorable in the book, carrying both the intimacy of a Nan Goldin photograph and the moral urgency of a prayer or biblical scene.

At times, Seuss takes the form of a latter-day Whitman, crafting extended lyrical lists in her continual search of herself and her Sublime, her beauty and her relief, “Poetry, the only father, landscape, moon, food, the bowl / of clam chowder in Nahcotta, was I happy … my breasts, feet, my hands, index finger, / fingernail, hangnail, paper cut, what is divine.” At other times, she writes in a more even, measured meter, as in the poem beginning, “I should have been in cinema. I should have been in paint / or founded a band. I am certain of nothing said the tattoo. / Where is home scratched the chickens. I should have met / the Stones when I had the chance. Should have let Keith / turn me inside out. So what if I ended up dead or crazy. / I am big but this feeling is bigger the silo whispered. I am / a movie screen drawled the pasture.” With their regular meter and folkloric images, these lines seem like the lyrics to some plaintive, strange old song. Throughout this book, the past, the “I should have,” is very present. So is mortality, as it thins out and opens up noiselessly like the cervix during birth.

In frank: sonnets, those who are typically excluded from mainstream culture and literature speak with central, powerful voices. Gay men, those battling addiction and illness, and those marginalized from American society are the focus of this complex and timely book. Just as Shakespeare immortalizes the “fair youth” of his sonnets, Seuss immortalizes the outcasts: their suffering, their songs, their Sublime. This is the work of an unusual and stellar American poet.

Published on August 9, 2021