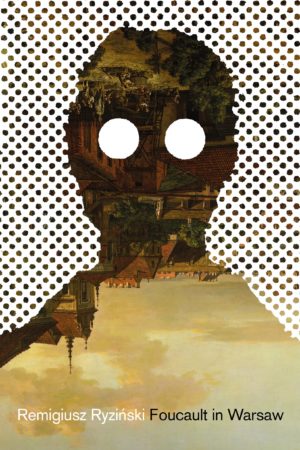

Foucault in Warsaw

by Remigiusz Ryziński, translated by Sean Gasper Bye

reviewed by Marcel Radosław Garboś

Since Poland’s state socialist system collapsed in 1989, the records of its police agencies and security services have gone to a government commission entrusted with the “prosecution of crimes against the Polish nation,” today part of the Institute of National Remembrance. Remigiusz Ryziński credits the Institute and its holdings for enabling his work, yet his use of this archive also challenges prevailing Polish narratives of collective suffering under surveillance and repression. Trained in gender studies, queer theory, and feminist thought, Ryziński belongs to the milieu of pioneering Polish intellectuals who investigate the experiences of people persecuted and ostracized because of their sexuality. He has authored four books, three of them reconstructing the inner lives of LGBTQ+ communities across Poland’s traumatic twentieth century while tracing how illiberal regimes have constructed sexual deviance as a problem to be monitored, contained, and excised since World War II.

Nominated for Poland’s Nike Award, and the first of these works to be translated into English, Foucault in Warsaw revisits a mystery surrounding its titular “hero,” Michel Foucault, one of the most iconic social theorists and gay intellectuals of the twentieth century whose fascination with deviance and social control has inspired academics and activists, including Ryziński. In 1958, while writing a doctoral dissertation on psychiatry and the invention of mental illness, Foucault crossed the Iron Curtain for the first time and settled in Warsaw, taking charge of a French cultural institution that had opened amid post-Stalinist relaxations. Less than a year later, Foucault hurriedly left Poland for his native France, a departure that biographers attribute to a romance with a younger, unnamed Polish man who worked as an informant for the secret police.

As Ryziński pursues the identity of this “boy” and the circumstances of Foucault’s flight, his story swiftly expands into an engrossing rereading of Warsaw as a gay metropolis in the 1950s and 1960s. His work is most original as a prosopography of gay Warsaw, assembling a collective portrait of a community whose largely irretrievable multitude of individual biographies Ryziński retraces through the spaces, objects, and experiences that once linked them. He describes a gritty, nocturnal “underground” in which cruising spots, such as parks, public urinals, and transportation hubs, hosted erotic encounters that could easily turn violent or deadly under the wrong conditions. Homosexuality, however, was not officially outlawed, and the frequenters of this “underground” also regularly appear in the more inviting settings of cafes, clubs, theaters, restaurants, and bathhouses where artistic and intellectual elites sometimes indulged in the company of younger “girlfriends” while the city’s renowned “queens” danced in drag.

If this Warsaw was a “close-knit community,” as his interviewees attest, Ryziński excels at capturing how its social and cultural pluralism sustained an informal economy that, pulsing with the flow of masculine libido, trafficked in foreign currencies, scarce commodities, and prized consumer goods. A handsome, mobile foreigner like Foucault could attract a stable circle of young men with his reserves of cash, vodka, and tobacco, not to mention his coveted connections to the West. “Foucault didn’t have much of a taste for alcohol at the time,” Ryziński writes, “but he took it on faith that in Poland everything could be sorted out either with its help or in its presence. The same with cigarettes. For a pack of Marlboros you could speed up a home renovation, get anywhere in a taxi, or ingratiate yourself with officials. Foucault could bring ten packets of cigarettes over the border (or, alternatively, fifty cigars or two hundred and fifty grams of tobacco).” Shadow economies are ubiquitous under state socialism, but Ryziński’s attention to the everyday transactions of his protagonists, peppered with reports of exchange rates, prices, advertisements, and newspaper headlines, lends memorable tactility to a story concerned with difference, desire, and border-crossing.

Foucault’s presence manifests itself powerfully in Ryziński’s meditations on the state surveillance operations that framed gay and lesbian communities as diseased, deviant populations to be counted, studied, and infiltrated. He most explicitly channels Foucault when he asserts: “There were no homosexuals in Poland until someone started keeping files on them.” These file-keepers were academics, doctors, and police functionaries who theorized about the erotic proclivities and psychological abnormalities of their subjects, concluding that gay men drew shadowy foreign contacts and likely engaged in illicit carnal activities, such as prostitution and pedophilia. For the secret police, recruiting young men to probe the sexual appetites of prominent artists or intellectuals could yield valuable material for blackmail, as Foucault would learn. Surveillance permeates gay Warsaw, and Ryziński suggests that it influenced a thirty-two-year-old Foucault’s writing on the confinement of the mentally ill, all as he sensed the eyes of the authorities fixed upon him like never before.

Accessible to readers with even a nascent interest in sexuality, social thought, or the Cold War, Foucault in Warsaw is a slender volume constructed of spirited, elegantly measured vignettes that circle the book’s guiding mysteries in fragmentary, chronologically discontinuous strokes, piecing together archival findings, ethnographic sketches, and the oral histories of gay men who knew Foucault in Warsaw. Sean Gasper Bye’s translation is an accomplishment beyond its literary merits, opening postwar Poland’s gay “underground” to a new audience that now extends far beyond academia. In writing this partially irretrievable history, Ryziński allows his own dreamlike scenarios to flow into gaps in the documentary record, conjuring up summer evenings perfumed with the “aroma of coffee, cigarettes, and weed” or imagining a dialogue between Foucault and his lover in a cafe where the “walls were the color of milky coffee or tea” and “the ceiling with its motif of gilded fir-cones in a molded frieze was like something from the pavilions of the great international expositions at the end of the previous century.” If the reader is careful in distinguishing where and why Ryziński engages in this style of narration, the book offers a rewarding introduction to the history of sexuality and everyday life under state socialism, and a refreshing vision of the Cold War through lives that straddle familiar borders and carve out spaces of precarious autonomy. In order to find Foucault in Warsaw, Ryziński leads us on an unexpected adventure to rediscover Warsaw in light of Foucault.

Published on March 1, 2022