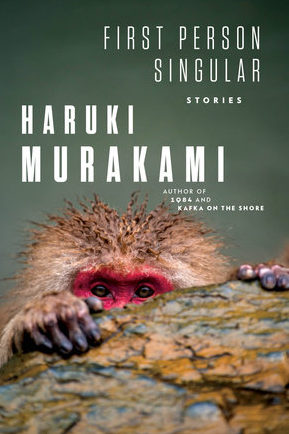

First Person Singular

by Haruki Murakami, translated by Philip Gabriel

reviewed by Erik Hage

One begins a new Haruki Murakami book with high expectations. There is his immense popularity, of course, but also the strange radiance of his work and his tendency to present mysteries or puzzles with no solutions.

These elements are certainly on display in his new story collection, First Person Singular, but the dominant mode here is memory. In this collection, an older narrator goes sifting through the events of his past, some of them surreal and unexplainable. Often, in the middle of a story, a memory will trigger another memory, through a sort of mnemonic leap; the result can be like a confusingly drawn map that means more to the creator than the reader.

Some of these experiences, as the narrator notes in “Carnaval,” are “nothing more than … minor incidents that happened in my trivial little life. Short side trips along the way.” However, as he notes, “these memories return to me sometimes, traveling down a very long passageway to arrive. And when they do, their unexpected power shakes me to the core.”

First Person Singular is about memory’s hold over us. Memories, in Murakami’s stories, aren’t so much about facts as they are about feeling. The narrator tells us in “With the Beatles” about “one girl … whom I remember well. I don’t know her name, though.” He does recall that she liked the Beatles, and he has retained an indelible image from 1964 of her rushing down a dimly lit school hallway, clutching the titular Beatles album to her chest, “skirt fluttering.” The kicker: “Other than that, I know nothing about her.” Although he will never see her again, the experience consumes him: “it was as if all sound had ceased, as if I’d sunk to the bottom of a pool.”

The meaning and significance of that memory are lost, “and the critical message contained there, like the core of all dreams, disappeared.” It is the memory of those feelings that he retains and to which he returns frequently, as “one of my most valued emotional tools, a means of survival, even. Like a warm kitten, softly curled inside an oversize coat pocket, fast asleep.”

There is an enchanting array of material in First Person Singular, from a talking monkey who steals women’s names to a dream encounter with jazz legend Charlie Parker to a meditation on baseball and poetry. There is also, at times, a calculated and somewhat peevish anticipation of criticism or interpretation. For example, in “Confessions of a Shinagawa Monkey,” the narrator feels the need to interject:

Theme? Can’t say there is one. It’s just about an old monkey who speaks human language … who scrubs guests’ backs in the hot springs, enjoys cold beer, falls in love with human women, and steals their names. Where’s the theme in that? Or moral?

The metacommentary reappears in “With the Beatles”: “[Question: What elements in the lives of these two were symbolically suggested by their meeting again and their conversation?]” It’s a peculiar way to express disdain for literary convention, particularly for a writer who has consistently defied convention through his creative mastery and vision.

Murakami also challenges readers’ sensibilities with “Carnaval,” which unfortunately never rises above its crass opening (though it aspires to): “Of all the women I’ve known until now, she was the ugliest.” This story could rightfully be compared with “On a Stone Pillow,” which starts out as a tale of a one-night stand with a woman whose face and name he can’t remember, but then manages to open up into a beautiful, sensitive meditation on her poetry. (She sent him a small, self-published book after the encounter.) Here, as ever, Murakami soars most when he circles around the central “theme” of this collection:

Even memory, though, can hardly be relied on. Can anyone say for certain what really happened to us back then? If we’re blessed, though, a few words might remain by our side … The dawn finally breaks, the wild wind subsides, and the surviving words quietly peek out from the surface.

Published on May 24, 2021