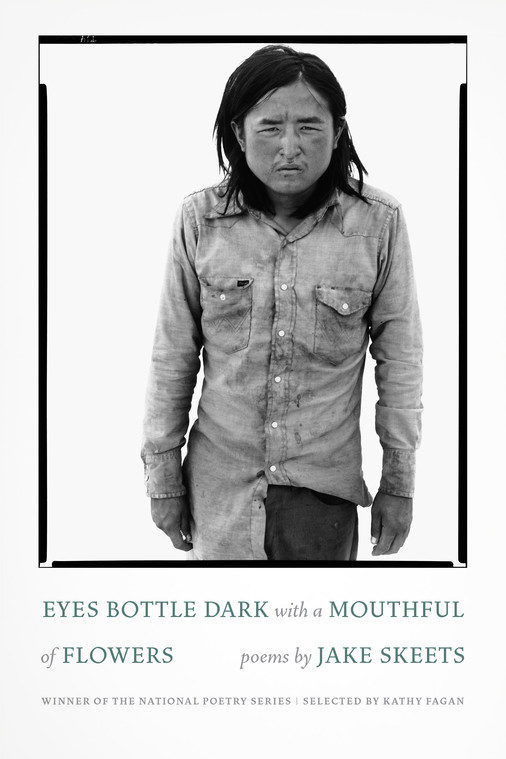

Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers

by Jake Skeets

reviewed by Paul Cunningham

“The Navajo word for eye hardens / into the word for war.”

In Jake Skeets’s Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, the American Southwest’s wild and grassy terrain collides with human bodies and nonhuman objects. A strange and uncanny poetic landscape emerges, one in which a dead cactus conceals a burrowing owl, where wild rose and sego lily lead us to a noisy truck radio. A Diné from Vanderwagen, New Mexico, Skeets writes poems that deal both with the organic terrain of Dinétah (Navajo homeland) and the industrial objects within it: bottles, coal, truck frames, hubcaps.

In poems like “Maar,” we follow larkspur, beeplant, and blue flax to dome-shaped ruins reminiscent of nuclear weapons testing facilities. Meanwhile, a “numb star” hangs over the horizon like a “burning bomb quiet as stone.” As recently as 2018, the Navajo Nation urged the US Congress to acknowledge the Native American workers who received no recognition or compensation after being exposed to radiation from uranium mines erected on Navajo land during the Cold War. By describing the “burning bomb” as “quiet as stone,” Skeets evokes the ghostly, unclean ruins of the over five hundred abandoned uranium mines that still stand today.

In addition to ecological catastrophe, Eyes Bottle Dark explores childhood trauma and queer longing, repeatedly mentioning an ominous swimming pool incident and following two boys as they face the challenges of forbidden queer desire. In “How to Become the Moon,” Skeets places his characters in this dark setting to elicit both sexuality and pain: “as you go down on him. He sees a boy, afraid of the deep end, / drowning in the swimming pool of your throat.” The boys cannot seem to experience pleasure without simultaneously experiencing sadomasochistic elements of violence: “to metal teeth / carburetor muscle beneath combustion”; “We kiss, caesura to ensure the blackening”; “My tongue runs across his shoulders, stone bells affixed to bone”; “fresh blood oozes at the lips.” Skeets’s poems of bodily destruction make ruins of queer indigenous youths, similar to the depleted uranium mines still standing on Navajo land. Implying queer lovemaking is something only possible at night, their pleasure is often halted by light, both natural and artificial: a sunset, or headlights. For instance, in “Táchééh” (the Navajo word for “sweat lodge”), even the most distant light is a potential threat to any chance of darkness:

hands petal on the shore

a spine

their bodies lap and tenor

they press their lips together

their torch skin

a distant sunset

distant headlight

distant city

distant brushfire

This concluding “brushfire” echoes throughout Eyes Bottle Dark, with its repeated references to “brushes,” “burning,” “cinders,” and “ashen” bodies. “Táchééh” climaxes with a hallucinogenic blending of human limbs, xylem, phloem, and sap—all in the surround of white space. We sense the many threats that these entangled bodies face, from the heterosexist gaze of distant surveilling headlights to global warming’s workings on an arid landscape.

For Skeets, in addition to printed text, the white space of a poem is what always remains. When the speaker looks into a “mirror” (on a page saturated by white space) he sees more than himself. He sees the pained faces of his family reflected back at him, and his father’s “boarding school soap bones” arranged and rearranged—a reminder of the colonial violence enacted on his father by way of the nightmarish assimilation tactics of boarding schools for Native Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. White space also feels like a space of entrapment, especially in the poems that share the title “In the Fields”:

dogs

maul

remains

like white

space

does

Some of these poems scatter letters across the page, and readers will most likely find their eyes drifting, trying to make sense of what looks like the remains of something once (but no longer) whole. Skeets’s poems often force readers to become scavengers for meaning, as in the long poem “Drunktown.” In it, Skeets reduces the owl—a sign of death and a sacred figure for the Diné/Navajo Nation—to the letters of the word itself: “an owl has a skeleton of three letters / o twists into l.”

For fans of Tommy Pico’s Nature Poem (which, like this book, feels like the opposite of the stereotypical nature poem) and Jeffrey Angles’s translation of Hiromi Itō’s Wild Grass on the Riverbank, Jake Skeets’s Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers is a reminder that Anthropocene poetry is most compelling when it acknowledges multiple Anthropocenes—indigenous, Asian, black, and others.

Published on March 20, 2020