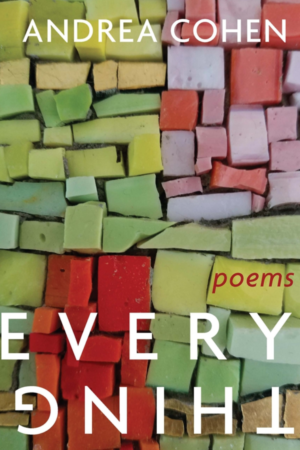

Everything

by Andrea Cohen

reviewed by Jason Tandon

A 2021 Guggenheim Fellow and current director of the storied Blacksmith House Poetry Series in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Andrea Cohen has published two poetry collections, both from Four Way Books, in the last two years: Nightshade in 2019 (which this reviewer highly recommends) and, this year, Everything. Divided into four sections, Everything contains ninety-nine poems, many of them just ten lines or fewer. American poet Lorine Niedecker’s nine-line poem “Poet’s work” offers an apt description of Cohen’s poetics. Advised by her grandfather to “learn a trade,” Niedecker declares:

I learned

to sit at desk

and condenseNo layoff

from this

condensery

Cohen’s poem “Craft Talk” hearkens back to Niedecker’s:

I paint

small birds,so when

they flyoff, their

loss mightseem

like less.

This is composition via eyedropper. Cohen deftly and remarkably breaks and punctuates lines for rhythm, emphasis, and irony. Like a jazz musician’s improvisations, her use of space and silence enriches rather than diminishes. It’s a poetics that will be appreciated by readers seeking an alternative to discursive poetry filled with digression and frenetic association.

You get the sense, from Everything’s epigrammatic style, that Cohen enjoyed writing this book. In the two-line poem “Announcement,” for example, she personifies flowers as nobility: “The peonies will / receive you now.” The first lines of “Openings”—“Eternity has closed its doors— / good riddance!”—might have been written by Emily Dickinson, Cohen’s playful compatriot. The speaker concludes in ironic defiance:

[ … ] I didn’t want

forever forever—just this

pear tree, branchesbacklit and the fruits

I can’t get to.

Though full of humor, the book touches on darker subject matter with poems like “No One” (government persecution), “The Bars Insist” (the prison system), “Bruise” (physical abuse), and “Protocol” (the attack on Pearl Harbor and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki). There are also many poems about love, desire, and the dissolution of romantic relationships. In “Pain and Suffering,” the speaker’s lover

[ … ] recorded

the silencebetween us—

played itback—made

me listen.

The poem “One-Two” portrays two lovers riding a train and explores the idea that despite becoming close with others, our individuated consciousnesses keep us apart:

Being two people, we

got on, and dreamingout one window

went two places.

Everything, as its title suggests, contains pain and loss as well as laughter—an unsettling counterpoint. The poem “Magician,” for example, combines Cohen’s comedic style with scathing self-deprecation:

Anyone can saw

a woman in half.The hard part

is sitting withboth halves at

breakfast, askingone to pass

the salt andthe other to

lick your wounds.That’s what

polyamory is—loving all

the charlatansyou are.

Despite the book’s slyness, Cohen’s speakers admit to rather than cover up their vulnerability and express a persistent need for human connection. The poem “Seaside,” a reflection on the challenges and precariousness of love, weds Cohen’s talents—it is lyrical yet exactingly composed. After planning a “day at the beach,” the speaker wryly comments, perhaps on the relationship itself:

nothing happens without

planning, because we had

to plant the sand andthe idea of happiness.

The poem ends with an acknowledgment of love’s exhilarating ephemerality:

[ … ] All our

pleasures were foraysinto wilds, were carry

in and out—likeour bodies, which

glistened, and were gone.

Everything’s final section contains its darkest poems about the horrors of humanity, among them the sardonic couplet “Safety Glass”: “The rose tint / isn’t optional.” Notes of resilience can be found in poems like “Tool Shed,” where the speaker finds various building materials,

evidence

that many

had come

before me

and from

some shattered

day made

a new

roof rise.

Even in this poem, Cohen maintains a hesitant tone through her clipped lines and commas, an equivocation that forms the basis for “The Blue Chair.” In what might be considered the book’s conclusive statement about human relationships, the speaker muses:

Maybe

we’re all nearly sound-

proof rooms and someone,

if we’re lucky, stands

at the heaviness

of our doors, meaning

to listen.

Hopefulness is conditional, the inner self—as the enjambed phrase “the heaviness / of our doors” suggests—a burden. “Meaning” indicates intent, rather than success. Andrea Cohen’s Everything is not a book of unflagging optimism, but readers who slow down for her spare, quick-witted, and emotionally resonant lyricism will be richly rewarded.

Published on February 15, 2022