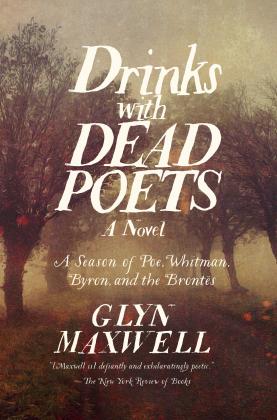

Drinks with Dead Poets: A Season of Poe, Whitman, Byron, and the Brontes

by Glyn Maxwell

reviewed by M. Lock Swingen

Glyn Maxwell’s Drinks with Dead Poets resists any easy classification. Part dream-memoir, part picaresque novel, and part defense of the poetic art form, the book is a wholly brilliant and often comical evocation of a mysterious university campus, its students and visiting lecturers, and the altogether precarious status of poetry within contemporary academia. Although not quite a sequel to Maxwell’s 2013 book On Poetry, a charismatic and personal how-to manual on the art form, Drinks with Dead Poets nevertheless expands upon that book’s essential premise, whereby Maxwell and his students find themselves entirely entangled in the poems they read.

Drinks with Dead Poets opens in mystery with the narrator, Maxwell himself, confessing, “I am walking along a village lane with no earthly idea why.” Soon enough, the poets that Professor Maxwell has been assigned to teach begin to appear in the village, very much alive. At first, not quite understanding the logic of his own dream world, Maxwell shrugs off a chance meeting with “some frock-coated emo” looking forlornly upon a stretch of farmland (who Maxwell finds out later is John Keats). Eventually, Maxwell wrangles the poets into his poetry course in order to engage his students.

It is a stellar line-up of poets: Dickinson, Coleridge, Yeats, Whitman, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Lord Byron, to name only a few. Remarkably, everything they say is lifted verbatim from their real-life diaries, correspondences, and essays.

Drinks with Dead Poets is in part a defense of poetry. “Music liberates you from the clock, the calendar, the schedule,” Maxwell says to one of his students. “Rhyme, form, meter, it’s the language reaching out to you: we’ve got this, we’ve done this, we were there before, we can help.” In addition to Maxwell’s own musings on the craft of poetry, which always teeter joyously between hard-nosed literary criticism and sheer exuberance for the art, Drinks with Dead Poets also reveals the insights and judgments of the visiting poets themselves. “If I—read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that’s poetry,” says Emily Dickinson. “If I feel physically as if—the top of my head were taken off! I know that’s poetry.”

And yet Maxwell’s students are notoriously difficult to impress. With searing accuracy, Maxwell depicts the vast and sometimes conflicting array of personalities attracted to university poetry seminars. Caroline, a middle-aged divorcée, has written a bitter cycle of love-hate poems about her ex-husband Ronald. Another student named Heath, a brooding hipster embarrassed by his own infatuation with poetry, consistently mocks Maxwell’s insistence on form and meter. And scarlet-haired Lily, who harbors a passion for poetry slams, explains to Maxwell that students these days just aren’t that interested in old-fashioned poetry readings anymore. With a twin sense of satire and love, Maxwell writes, “Like most poets of the day and age when we set about teaching, I am haplessly cast as counsellor, shrink, trainer, mate, provocateur, Fool in the Lear sense and fool in the fool sense.”

The mysterious country village in which Maxwell finds himself at first appears tranquil and bucolic, but Maxwell’s dream world also conceals a seedy bureaucratic underbelly. The “Academy” where Maxwell teaches his seminar seems suspicious of—if not downright hostile to—Maxwell’s teaching methods, his rapport with his students, and perhaps even his mere existence at the university. For example, Maxwell teaches his class in the cramped side room of a dingy hall off campus. The university administration even overrides Maxwell’s own poetry readings and hires a celebrity to perform a rap version of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” while Samuel Taylor Coleridge himself looks on, thankfully unfazed and fortified by copious glasses of red wine. In Drinks with Dead Poets, poetry seems constantly under attack, besieged by an institution and its students who are angst-ridden over a lack of understanding of what poetry exactly is or should be.

And yet Maxwell teaches his seminar with verve. The antics, exploits, and adventures that Maxwell and his students get up to with the visiting poets are nothing short of splendid. Maxwell steadies a drunken Keats, for example, after the poet chucks up one too many cherry brandies (Drinks with Dead Poets is aptly named). He watches in horror and awe as Lord Byron flirts with his enraptured female students and he spars with Edgar Allan Poe over the techniques of good storytelling. Eventually, the students and even the Academy prove not immune to Maxwell’s and the visiting poets’ appetite and passion for poetry. Near the book’s end, one of Maxwell’s students urgently asks Lord Byron what he thinks poetry is:

“’What is poetry?’

He sipped his wine and said, rather quietly after thought: ‘The feeling of—a former world and future.’”

Glyn Maxwell’s brilliant new work defies categorization. It is not fully memoir or comic novel or literary criticism. No matter the genre, let us hope that Maxwell’s wonderfully strange dream world, where the great dead poets are very much alive and very much human, will live on in renditions to come.

Published on September 1, 2017