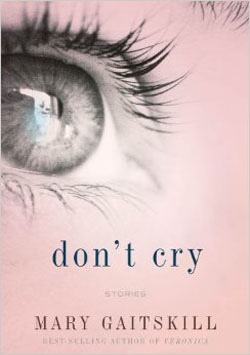

Don’t Cry

by Mary Gaitskill

reviewed by Lisa Nold

Bravery and poise are two essential ingredients of fine writing and they are in full effect in Mary Gaitskill’s newest collection of stories, Don’t Cry. Gaitskill, who is widely considered one of contemporary literature’s boldest writers, was a National Book Award finalist for her novel Veronica, and a PEN/Faulkner Award finalist for her collection of short stories Because They Wanted To. She is also author of the novel Two Girls, Fat and Thin, and the collection Bad Behavior.

From the first page of Don’t Cry, the reader is faced with the pain of the human condition. Gaitskill’s opening story, “College Town, 1980,” begins with a close description of the story’s heroine, Delores, who is adrift in Ann Arbor, Michigan:

Delores did not look good in a scarf. Her face was fleshy, her nose had a bulby tip, and her forehead was low. Her skin was coarse and heavy for a woman under thirty, and the tension in her face was such that a quick glance gave the impression that she was grinding her teeth, although she was not.

Virtually every line of Gaitskill’s prose is clear and sharp, and it is with pure fearlessness that she weaves stories of family enmity, human failure, pride, loss, and love. In “An Old Virgin,” the main character, Laura, is unhappy at midlife as her father is slowly dying. With a delicacy that few writers can achieve, Gaitskill presents the real and wholly conflicted emotions of resentment and love that surface for this character, especially in light of the father’s formerly negative behavior. At one point she observes his reaction to the hospice workers:

He would frown and even slap at the workers, and, in the fierce knit of his brow and his blank and furious eyes, Laura remembered him as he had been, twenty-five years ago. He’d been standing in the dining room and she was walking by him and he’d said, “What’re you doing walking around showing your ass? People’ll think you’re selling it.”

The thing that saves Laura from destruction, and indeed saves all the characters in this book, is the persistent countercurrent of love, or at the very least forgiveness, that enables the characters to fight back. Without an ounce of sentimentality, Gaitskill crafts fully realized and highly vulnerable characters. Moreover, she has an expert ability to move forward and back in time when disclosing a character’s psychological state. She can take a glance by the father on his deathbed and telegraph it back to an important event in the past and then bring it forward again without disturbing the flow of the story.

Armed with these stunning technical skills, as well as a beautiful grasp of language, Gaitskill builds a strong narrative foundation for each story. In “Description,” she tells a classic story of human envy that, in its construction, recalls James Joyce’s “A Little Cloud.” In Joyce’s short story a successful writer, Ignatius Gallagher, brags to his old schoolmate Thomas Chandler in Dublin. In “Description,” Kevin, also a successful writer, brags to Joseph in New Paltz, but in both stories the less successful of the two men suffers similar feelings of defeat and self-loathing.

Beyond their fine construction, the ordering of these stories is also admirable. The opening story is set in 1980 and the closing story in the present day. There are thematic symmetries and effects, such as the use of light and darkness, that dovetail from one story to the next. In the case of “Description” and “Don’t Cry,” a female professor named Janice is elevated from a background character in one story to a primary character in the other. Even more interesting to Gaitskill fans, several characters in “College Town, 1980” are drawn from the story “Orchid,” which appeared in Because They Wanted To.

Gaitskill never once gives up in her effort to dazzle the reader in Don’t Cry. She serves up magic realism in the beautifully written “Mirror Ball,” and takes on the limitations of feminist philosophy in “The Agonized Face.” Other notable stories are “The Little Boy” and “The Arms and Legs of the Lake,” both of which address issues of loss, suffering and hope in a post-9/11 world.

Will this book please everyone? Probably not. Gaitskill’s real-life imagery is often explicit and the language is shocking in places. Yet, as so many canonized writers have already proved, pleasing everyone is hardly the goal of a truly brave and timeless work of literature.

Published on March 6, 2015