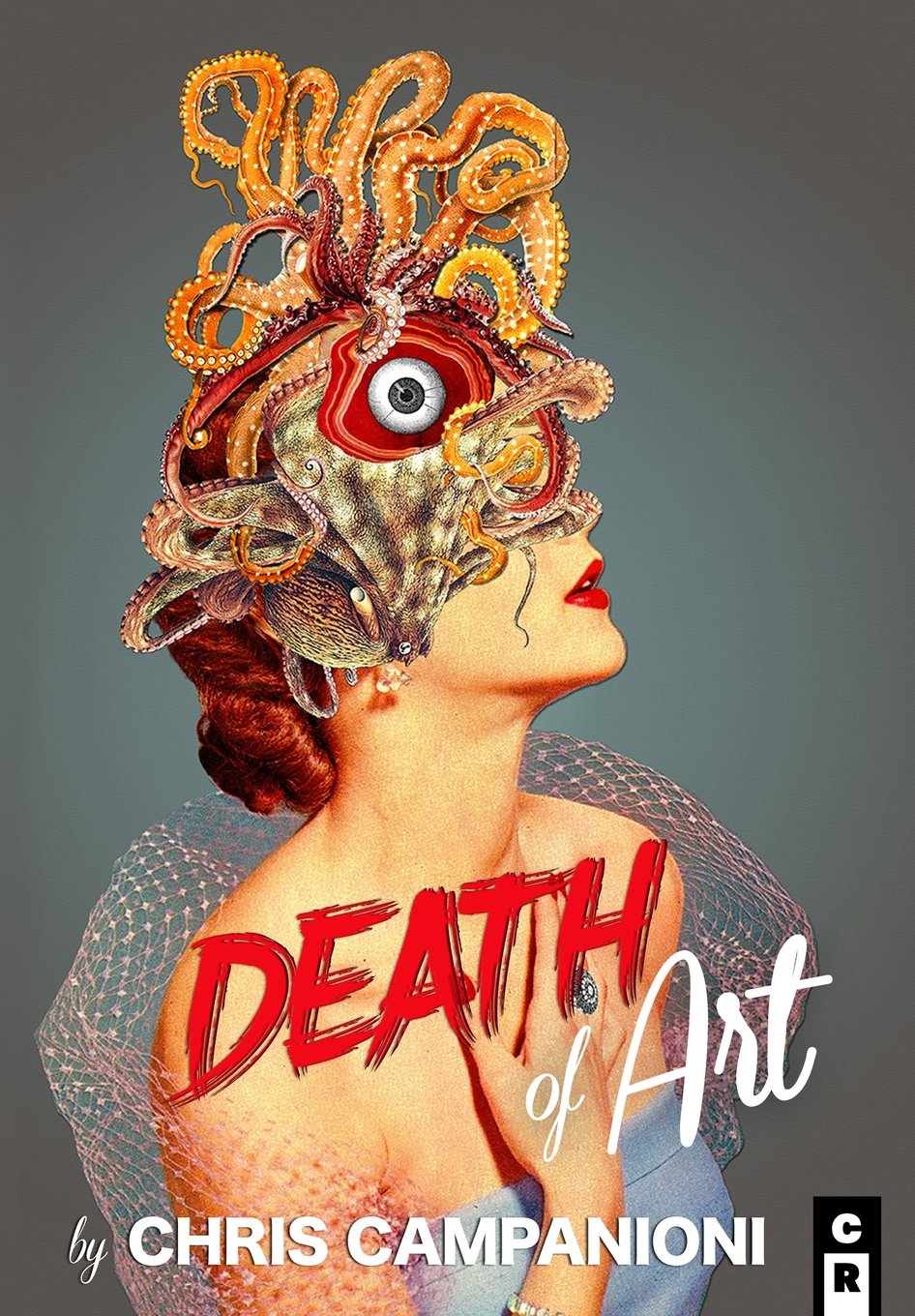

Death of Art

by Chris Campanioni

reviewed by Gabriel García Ochoa

In 1925 Viktor Shklovsky, the Russian writer, literary theorist, political activist and film critic, and one of the most important exponents of Formalism, published a now-famous essay, “Art as Device.” In it, Shklovsky discusses what he calls “defamiliarization, the process by which art makes the mundane unfamiliar, and in so doing, reminds us of its beauty: “habitualization devours work, clothes, furniture, one’s wife, and the fear of war … art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.”

Chris Campanioni’s third book, Death of Art, follows Shklovsky’s maxim, giving its readers a gentle slap on the cheek to shake off the slumber of the habitual. The book is a memoir, but an unusual one. In 2009 Campanioni was named “the sexiest man alive” by DNA magazine. He is a former underwear model; before that, he was a journalist with a background in literary studies. In his own words, he is “a writer, turned model, turned writer.” Like Campanioni, Death of Art is complex, a hybrid text, a combination of prose and poetry. Following the narrative of Campanioni’s modeling years, it examines our cultural obsession with the image and how lately this obsession has acquired new forms through social media and pop culture. More importantly, the book looks at how this fixation affects our relationship with, and understanding of, art.

Clearly, Campanioni is well-positioned to discuss these topics. He reflects on his career in the fashion industry with a dual lens as both model and intellectual. Self-analysis is part of every memoir, but in Campanioni’s case it acquires an added interest, given the apparent contrast between his roles as writer and model. The result is fascinating.

Death of Art takes us to the eye of the storm in a world where everyone vies for another click, another “like,” more views. Although not overtly, it invokes Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation, left, right, and center. What happens when we start to favor the image above all else? Can those images become the things we take to be real? Is intimacy possible in such a world? Are we happier when everyone is looking at us? Do we love more? Are we loved more? Or are all those hopes, energy, and aspirations pointlessly sacrificed at the altar of representation? Campanioni describes what it’s like to become a public canvas onto which people project their ideals, the pressure of being shaped by the image that the Internet presents of him, and in that online universe of endless refraction, his reaction to that reaction.

I began to understand that even I had no control over the performance any longer: I had built an image of me that would outlast me. In truth, the image didn’t just outlast me. It replaced me. The same way that today, our carefully curated online presences replace our physical ones.

Death of Art glorifies and subverts a culture that strives for the commodification of self and soul, in an age when identity and privacy have become a product. Is art powerful enough to dispel the crassness of this culture? Can it defamiliarize it for us so that we may glimpse its beauty? Campanioni’s answers to these and other questions are pleasantly surprising.

Reading Death of Art brought to mind another author, the Chicana poet and cultural theorist Gloria Anzaldúa, best known for her book Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Like Anzaldúa, Campanioni has a mixed cultural background, which he touches on in the book. He is Cuban on his father’s side, Polish on his mother’s. Different sections of his memoir alternate swiftly between English and Spanish, in both prose and poetry, without the use of italics (this is very characteristic of Anzaldúa’s writing).

Anzaldúa stood at the intersection of two seemingly incompatible identities. She was not a model and intellectual, but she was derided by poets for her academic work and criticized by academics for her poetry; ostracized by white feminists for her Mexican heritage, and by the Latin American community for being queer. As a consequence, Borderlands/La Frontera is a striking amalgamation of memoir and social critique, poetry and cultural theory. Death of Art does not have the depth or intensity of Borderlands/La Frontera, which has become a canonical text in the field of cultural studies, but it offers flickers of that complexity and the possibility of very interesting future texts from Campanioni.

Campanioni’s writing is playful, unflinching. His prose is poetic and his poetry often prosaic (in both senses of the word). It is a much-needed reminder of our endless potential for duality, in a world that too often suggests only polarity is possible.

Published on April 4, 2017