Dear, Sincerely

by David Hernandez

reviewed by Calista McRae

This short book, David Hernandez’s fourth, first caught my eye for its humor—it’s a brilliant example of how poems can be funny in free verse, without comic rhymes or bouncing meters. Here, for instance, is the opening of “Master Sommelier Blind-Tastes a Glass of Water”:

This glass: Did you rinse it?

I ask because there’s sediment

swirling like a time-lapse of a galaxy

if stars were debris

without their shining.

Hernandez has fun with his cartoonishly fastidious, snarky speaker. The mere “nose” of the water prompts a disgusted “wow, who / shoved me into a swimming pool?”

It’s positively tap. I’m also picking up

some witchgrass

and moneywort, it’s not

easy with all this sodium chloride

assaulting my sinuses. Penny,

I’m detecting old penny, a hint

of natural gas.

You can picture this poem being read aloud. Its run-ons and deflations come to life within these jagged lines: “I have to say / I am / hesitant to taste this.”

While this collection is often effervescent, its comedy braces, disconcerts, and occasionally haunts. Its thirty poems encompass anti-gay protests, black sites, and what one’s taxes might fund: one speaker tells himself, “my pennies went to another drone, / I chipped in for flight, not flame.” In the water-tasting poem discussed above, a similar move—from entertainment to a shudder—occurs as the sommelier reaches a verdict:

I’m going tap

from a brass faucet, from a region

ruined by fracking.[…]

I’m calling

United States, Pennsylvania,

Laurel Highlands, 2013 vintage.I have to say: This faucet you found?

The small town where you found it?

Their mayor does not

love them enough.

Most of this monologue would not look out of place in a sketch spoken by John Cleese; the poem keeps up its persona even as it fastens itself onto the actual world, where mayors, in a fine understatement, do “not / love” their small towns enough.

While the sommelier drinking tainted water lays out, in slow motion, how humor can chill, the clear-cut template of verbal performance and grim punchline is only one of Hernandez’s techniques. One of the book’s most appealing poems is “All-American,” which shuffles through contradictory identities as if trying to randomize a deck of cards:

I go to church

in Tempe, in Waco, the one with the exquisite

stained glass, the one with a white spire

like the tip of a Klansman’s hood. Churches

creep me out, I never step inside one,

never utter hymns, Sundays I hide my flesh

with camouflage and hunt. I don’t hunt

but wish every deer wore a bulletproof vest

and fired back. It’s cinnamon, my skin,

it’s more sandstone than any color I know.

These lines roll along quickly but without hurry, moving from sardonic, exaggerated simile to gleeful slang (“Churches / creep me out”).

The end of “All-American” focuses on the workers whom the professional class tend to ignore: those who squeegee windows, or “gather the shopping carts into one long, / rolling, clamorous and glittering backbone.” The poems of Dear, Sincerely are at their best when making such thoroughly strange associations. The book is pervaded by sudden compressions and expansions of perspective; witness how Hernandez telescopes the solar system into a glass in the “Master Sommelier” poem.

Hernandez finds poetic forms in equally unexpected places. “Comment Thread in Response to ‘100 Best Flowers of the Year’” brings one of the Web’s least-promising genres up against one of the most poetical of poetic subjects. A resemblance emerges: these varyingly nested sentences, with their tonal skirmishes and gaps of white space, work precisely in the manner of the comments section.

How is hollyhock

better than Delphinium, better than the ruby chandelier

of a Spider lily?[…]

Could someone please tell me where the hell is calla lily?

Calla lily is doubled-over by a riverbank puking milk.

The voices are fanciful and puerile by turns. “Fuck larkspurs!” one commenter begins.

Flowers draw the jokey and the sober together throughout the book. One poem, spoken by a hospital’s dreary powder blue “Paper Gown,” sees its wearer as “[w]ilted,” “a lone morning glory / bending underneath the current / from a weed whacker”—a diminished, contemporary version of the warrior-as-drooping-poppy seen in the Iliad and in Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red. Earlier, an explosion viewed on a screen resembles “a black bouquet falling away / down the center of [a] monitor.”

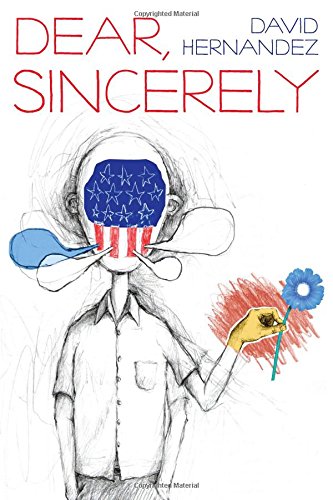

And there is also a flower—some kind of daisy—on the cover of Dear, Sincerely. It is held by a figure whose face has been replaced by the pattern of the American flag: it recalls both the flower offered in nonviolent protests and the squirting flower of a clown.

Published on November 8, 2016