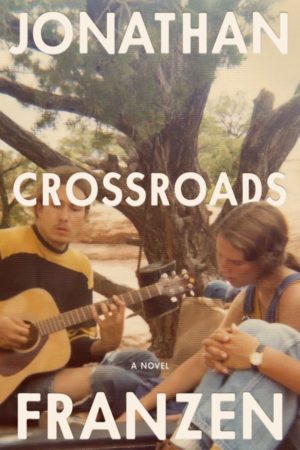

Crossroads

by Jonathan Franzen

reviewed by Caroline Tew

After the six-year hiatus, to say Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads was highly anticipated is something of an understatement. Some eagerly awaited the nearly six-hundred–page novel, others wondered what Franzen had left to say about middle American families and their struggles, while a final camp lamented how much attention this one book was getting. To my delight and surprise, I found Crossroads—the first in a trilogy archly titled A Key to All Mythologies, in reference to George Eliot’s decrepit scholar Edward Casaubon—to be an improvement on Franzen’s earlier work. Mainly, in his ability to write about women.

Crossroads follows the lives of the Hildebrandts, a family of six headed by Russ, the pastor of a run-down suburban church. While Russ pursues one of his parishioners, Frances, his wife Marion begins dissecting her own trauma in therapy. Meanwhile, their eldest son Clem has come back from college to fight in Vietnam, their daughter Becky has found God (and rock ’n’ roll), and another son, Perry, is forming a drug habit; their youngest, Judson, looks helplessly on as his family falls apart. The family members are too caught up in their own troubles to take much notice of one another, yet Franzen does an excellent job of tying together the disparate inner lives of the Hildebrandts. This behemoth of a story feels cohesive and propulsive.

Franzen’s decision to set Crossroads in the seventies, rather than defaulting to the present as he usually does, may have to do with his intention of writing an intergenerational trilogy. But mostly, I suspect Franzen wanted to put his finger on the pulse of a unique moment in American history. This book investigates the complicated feelings of people like Russ, an activist during the civil rights movements of the sixties, now watching his children join the counterculture movement of the seventies. Father and son argue over the merits of patriotism versus passivity. Clem is severe on the pacifist Russ: “[W]hen it’s time to put your money where your mouth is, you don’t see any problem with me being in college and letting some Black kid fight for me in Vietnam.” And the eponymous Crossroads youth group—helmed by Russ’s archenemy Rick Ambrose, a foulmouthed young man with a gift for connecting with teenagers—has a uniquely seventies atmosphere. Within the cauldron of Christian values and free-loving counterculture, Perry quickly learns that a “public display of emotion purchase[s] overwhelming approval.”

While some of the more humorous moments of the novel take place in the strange world of the Crossroads group, ultimately the novel’s strength lies not so much in its period detail as in its ethical ponderings. In fact, the most interesting plot lines of Crossroads revolve around religion; Franzen’s concerns could work, quite frankly, in almost any era. There are the obvious struggles Russ faces, as he pursues Frances and as he tries to reconcile his self-image as a hip liberal with his inability to connect with the youth group. But it’s Perry, the teen drug addict and slacker-genius, who poses the book’s most interesting conundrum:

My question … is whether we can ever escape our selfishness. Even if you bring in God, and make Him the measure of goodness, the person who worships and obeys Him still wants something for himself … If you’re smart enough to think about it, there’s always some selfish angle.

Perry can’t get out of his own head—even his acts of kindness are tainted by ulterior motives, whether that’s “the feeling of being righteous” he derives from them or the promise of “eternal life.”

Franzen has long been criticized for not writing (or talking about) women very well, and it does feel as though he’s taken some of the criticism to heart this time around. Although Crossroads is far from perfect, Marion does give Russ a piece of her mind: “Oh dear … You want to argue with me? I wouldn’t recommend it.” Franzen still has a long way to go, though; Marion believes herself to be fat at only 140 pounds (a sentiment the narrator seems to share), and Becky comes off as the archetypal It Girl and teen rebel.

Sometimes, too, Franzen’s impulse to narrate every detail works against him. The sex scenes are particularly painful, although in some cases rightfully so. Certain moments, such as Russ’s unholy lusting after Frances, are purposely unsettling: Russ had “never profaned the church by abusing himself in his office, but he was so deeply in the thrall of Frances that he was tempted to do it now.” Yet every sex scene, illicit or otherwise, is so crudely described that it’s difficult not to be thrown violently out of the narrative by a heightened awareness of Franzen’s choice of words. “He caught an exciting, catfoody whiff of degraded semen” stands out as a particularly damning example.

Those who bemoaned the release of a new Franzen novel may be pleasantly surprised by Crossroads. It’s a promising start to what sounds initially like a pretentious undertaking. However, those expecting the next Great American Novel may wish to temper their expectations. While worth the rather long read, it’s by no means as earth-shattering as the hype implies.

Published on February 3, 2022