Coming to That

by Dorothea Tanning

reviewed by Henry Hughes

Lifting a glass of champagne in an evening ritual, Dorothea Tanning would joke among friends that she was the “oldest living emerging poet.” An active visual artist for most of the twentieth century, Tanning turned to writing later in life, publishing two memoirs, Birthday (1986) and Between Lives: An Artist and Her World (2001), a novel Chasm (2004), and two books of poetry, A Table of Content (2004), and Coming to That, published just five months before her death at the age of 101 at her home in New York City.

“Free Ride” heads the collection with all the exuberance and lightness of youthful discovery and Tanning’s touch for subtle rhyme and easy idiom.

Did you see the satellite,

our planetary spy,

cast its vibes around the sphere?And, crazed as a lost idea

wild to find its mind,

in no time flat it had me out therereeling in a surreal sky.

Still gazing upward, “Trapeze,” with its more metric and lineal apparatus, beautifully captures the paradox of an aerial circus act that requires extreme discipline and precision, yet is, one might say, utterly crazy.

the wave to the crowd, a flutter and

spins in rising air for the letting go;

then the vertiginous game with suddenwind, yellow skirts lifted in spiraling

exuberance before the plummet.

The dizzying actions in these opening poems are not unlike Tanning’s early painting style, in which meticulously precise images were spun and melded in surreal ways. Tanning was thrilled by the émigré Surrealists of the 1930s and 40s, including the poet André Breton, Salvadore Dali, Kurt Seligman, and the German painter Max Ernst. Tanning met Ernst in New York, and they were married in 1946 in a double wedding with Man Ray and Juliet Browner. Stravinsky raised the toast.

True to the second Modernist revolution, Tanning and Ernst stressed the power of the unconscious, free association, and automatistic drafting to tap the deeper “core of being.” Tanning plunges into the dream-well of language in poems like “No Snow,” “Sand/Dollars” and “To the Rescue,” which draws on the experience of living in Sedona, Arizona, and reminds us of the Mexico-inspired paintings and writings of Leonora Carrington: “Think of a lizard as a spot of day-glo green / . . . Lost in this kitchen of chrome-souled / recipes for oblivion . . .” And we can’t help thinking of Elizabeth Bishop when reading Tanning’s self-correcting “Peruvian”:

It might be time to research the thing

instead of always saying “Peruvian,”

while it may not be Peruvian at all—

The poem continues to playfully scrutinize Modernist obsessions with “Primitivism” and native totems and ceremonies as unadulterated sources of human energy and truth.

. . . a chunky shaman eyed

me, shook his red-tipped

wand at me, his mask for out of body

states defying me or anyone to

probe his tribal truths disguised

in black and terra cotta paint, the

penis a badge, perhaps of courage—

Although more sexually daring than Bishop, who wrote about Brazil in the early 1960s, both poets were awed, fascinated, and in the end, skeptical of exploiting South American indigenous culture as a way of understanding our own modern “flimsy masks.”

Bishop (born in 1911) and Tanning (born in 1910) are close contemporaries, though Tanning outlived Bishop by more than thirty years. Perhaps Tanning’s late start as a poet allows her to write so unselfconsciously, so unconcerned with the problems of simple meaning and the intellectual gravity of the Modernist tradition. Unfettered by early successes in literature, she steps blithely into the other language of talking and writing.

If Art would only talk it would, at last, reveal

itself for what it is, what we all burn to know.As for our certainties, it would fetch a dry yawn

then take a minute to sweep them under the rug:certainties time-honored as meaningless as dust

under the rug. High time, my dears, to listen up.

When a hundred-year-old woman tells you to “listen up,” you might expect long yarns of nostalgia, and though there are occasional glances at “old photographs / under the lamp” and a lovely remembrance of a sea captain uncle, Tanning’s memory generates a moving, mystic dance in time that feels like today and beyond.

She went her way in shade, pared

her nails, wore a hat. Once in a blue

moon she would close her eyes and seeagain what a million years ago

had been, for her, the right

and wild thing . . .

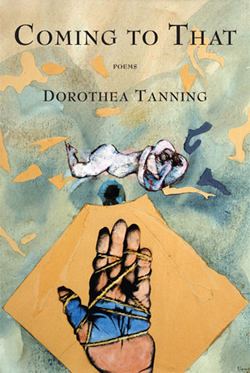

These lines beautifully complement the book’s cover image, “Cassiopeia,” a collage Tanning created in 1988 using torn pieces of watercolor paintings and a photocopy of her own hand.

A discernable presence of art and literature inhabits this book, ending with “Artist, Once,” which draws the centenarian’s circle back to that twenty-five-year-old woman arriving in New York in 1935, or to any young, aspiring artist arriving in the city of dreams.

That was in a room for rent.

It had a window and a bed,it was enough for dreaming,

for stunning facts like beingat last, and undeniably

in NYC, enough to holdenfolded as in pregnancy,

those not-yet-painted works

Coming to That is the perfect fulfillment of an artistic life—to live very long and deliberately, to maintain a sharp mind and serviceable body, soaking up a multitude of paintings, films, plays, ballets, operas, books, songs, poems (and, yes, champagne) and bringing it to bear on one’s creative endeavors, right to the very end and into the future.

Published on May 22, 2014