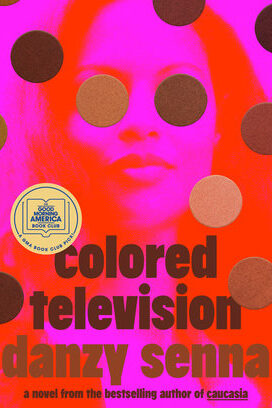

Colored Television

by Danzy Senna

reviewed by Andrew Koenig

Danzy Senna’s Colored Television is many things: a satire of the entertainment industry, the story of a woman in a midlife crisis, and a commentary on Hollywood’s exploitation of racial diversity. There is plenty to admire about this novel, namely its well-wrought central character, unpretentious prose, and acerbic humor. Its treatment of larger themes jars against its light tone, creating an unsettling and at times uneven story.

The novel opens with protagonist Jane Gibson at loose ends, drifting from one house-sit to another in Los Angeles with her husband Lenny and two children, Finn and Ruby, in tow. When we meet them, they are living in Silver Lake at the house of Jane’s friend Brett, a short story writer turned TV hack who has struck it rich with a black zombie apocalypse show. Meanwhile, Jane, an untenured teacher of creative writing at a liberal arts college, is putting the finishing touches on her second novel, a sprawling, Roots-like history of “mulattos” in America. (This is Senna’s preferred choice of word over “biracial” and “mixed.”) When Jane’s book does not pass muster with her agent and editor, she grows desperate—without a contract, she can’t get tenure, and without tenure she and her husband will never afford a home in the coveted neighborhood of “Multicultural Mayberry,” modeled on South Pasadena.

Jane and her family live in a state of precarity familiar to creative professionals in Los Angeles—cultural capital-rich, house-poor. When Jane decides to pitch a show to up-and-coming television producer Hampton Ford that combines elements of her own novel with ideas shared with her by her landlord, friend, and rival Brett, she sees a way out of her predicament, only to find herself caught in the arms race for diversity in television. Jane finds herself seduced by an industry that doesn’t have the disadvantages of novel-writing—solitude, penury, misery—but is soon overwhelmed by its fast pace and relentless instrumentalization of identity.

Colored Television concerns itself throughout with the waning cultural position of the novel in a video-saturated era. As Jane remarks in a conversation with her husband,

There’s so much desperation in selling your own work. You have to cultivate a persona to hawk a product that, let’s be real, nobody really wants. You have to be multicultural and wise. Be somebody with a position. You have to tweet increasingly inflammatory things about your vagina just so people will buy your book. A book nobody wanted or needed in the first place. Because they already have TV.

In a series of frenetic meetings with Hampton Ford, Jane attempts to reduce her epic of mulatto life into a digestible Hollywood narrative. Her artistic reflexes make this difficult, and their brainstorming sessions offer comic relief. Some of the book’s most humorous passages are episode synopses, the funniest of which is about a mixed-race family that brings home a Labradoodle, leading to various hijinks.

The book’s grander ambition is to imagine an untragic mulatto—a figure who has been the stuff of Hollywood melodrama for nearly a century, famously epitomized by the character Peola in Imitation of Life. What we ultimately get is not a success story but a record of an author’s frustrated attempts to dismantle stereotypes, seemingly impossible to do in today’s publishing and entertainment environment.

Senna details Jane’s marital and parenting difficulties alongside her creative struggles: her son Finn shows signs of autism (a word Senna is careful never to use in the book), and her daughter Ruby experiences the usual angst of American girlhood, literalized in a refusal to play with her black American Girl doll. Jane’s obsession with living in a desirable area of Los Angeles leads her to consider the outlandish possibility of moving into a nursing home with her family rather than to Burbank, which in this book is depicted as a kind of perdition (and, incidentally, the location of Warner Brothers Studios). At one point Jane chases down Hampton Ford at a house on Amalfi Drive, one of the streets destroyed in the recent Palisades Fires; hell and heaven are not so far apart.

Professional and housing anxieties precipitate an identity crisis for Jane. Is she black or white? A true writer or a wannabe? A success or a failure? In the spirit of TV writing, I will offer here a spoiler alert. Colored Television is a tale as old as Hollywood: that of a struggling writer whose story gets stolen by her producer. Hampton Ford rips off Jane’s show ideas, just deserts for the original sin of stealing her show’s premise from Brett. Hollywood exacts its vengeance, and the end of the novel leaps forward in time—the oldest trick in the book of soapy prime-time television—to show an older-but-wiser Jane nevertheless living the dream in Multicultural Mayberry, marriage and family still intact.

Senna’s Los Angeles is a sunny unaffordable paradise full of thin, chipper moms and avaricious men, all driven onward by the bromides of therapy and the pursuit of wealth. The book’s moody depiction of Jane’s internal state in combination with the surreal landscape of brilliant sunsets, endless strip malls, and innumerable accessory dwelling units lends her often petty emotions gravitas. Less compelling are the parts about the midcareer creative writing instructor’s usual complaints—dull students, precarious employment, writer’s block.

What is best is Senna’s wry depiction of the Hollywood machinery, which turns adversity into profit. Various bit characters populate the book, including a “racial alchemist” named Wesley. As Wesley comments, “Jane, when I look at your chart, I get a lot of confusing signals. I see zigzags and negations. It’s like a census questionnaire. Hispanic, non-Hispanic. Other. That kind of chaos.”

Colored Television itself zigs and zags. Nearly every relationship in the book is one of theft, creative and personal: white people stealing black people’s trauma, producers stealing writer’s ideas, men and women stealing each other’s spouses. Senna is unafraid of using the tricks of TV—melodrama, sudden twists—to tell an entertaining story and advance a scathing assessment of today’s diversity-entertainment ecosystem.

Published on March 13, 2025