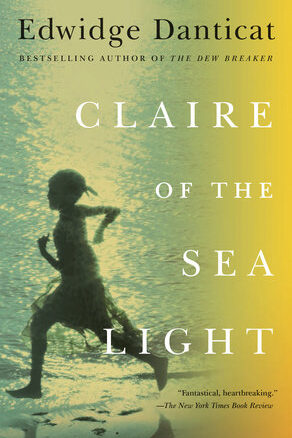

Claire of the Sea Light

by Edwidge Danticat

reviewed by A. Naomi Jackson

This year will mark twenty years since Edwidge Danticat’s first book, Breath, Eyes, Memory, was published and selected for Oprah’s Book Club. Danticat has since published short story collections, novels, and creative nonfiction, edited anthologies, and produced a film. Her work across genres has changed the landscape of American literature with lyrical, unflinching portraits of life in Haiti and in the Haitian diaspora, transforming her readers’ sense of the Caribbean and of immigrants’ experience in America. With each new book, Danticat shows even more of her capable hand. Now, with Claire of the Sea Light, Danticat stuns us again.

Danticat has addressed tragic events in Haitian history in her previous work—the 1937 massacre of Haitians in the Dominican Republic in The Farming of Bones, the tyrannical rule of despots and their mercenaries in The Dew Breaker. Her newest novel takes on the everyday tragedy of grinding poverty and, more specifically, how some Haitian parents give their children to wealthier families to become restaveks (which means literally “to stay with”). These children exchange chores for room and board in an informal institution some describe as modern-day slavery, while others call it a practical, if terrible, solution to scarcity. The book opens on Claire Limyè Lanmè’s seventh birthday, when her father, a poor fisherman, makes the wrenching choice to hand over his daughter to a shopkeeper who he thinks will be able to better care for her. Claire decides to run away rather than face her fate, and the book hinges on whether and how she will return home.

Claire of the Sea Light captures the reader’s attention both because we want to know what will happen to Claire and because we are hooked by Danticat’s enchanting, cinematic descriptions of the landscape and the rich lives of her characters. There is, as in all of Danticat’s writing, the thrill of her gorgeously rendered details, for example, “the baby spider birthmark that grew into a full-blown black widow when her stomach swelled during those days she was menstruating.” Or Claire’s father, recalling the sight of his wife, who’d died just after giving birth to their daughter: “He was shocked to see that, in death, though the baby was no longer in it, her stomach was still round like a frigate bird’s bill.”

More so than in the books that preceded it, we hear characters in Claire of the Sea Light speak Kreyòl. Perhaps the predominance of Danticat’s native tongue in this novel is an outgrowth of the freedom enabled by her extended life in letters, recognized most recently when she was awarded a MacArthur Foundation’s “genius” grant in 2009. “Fòk nou voye je youn sou lòt,” or “we must look after each other,” is repeated throughout the text, as characters consider the responsibility of caring for each other. These and other phrases in Kreyòl combine to make this novel transporting, and deeply embedded within a Haitian cultural context.

Danticat revisits the fictional Haitian community of Ville Rose, a thorny, ethereal place, in Claire of the Sea Light. Ville Rose provides Claire, her father, and her neighbors a sense of belonging as well as a kind of stranglehold on change, binding its residents to cycles of reactivity, ancient memories, and holding patterns of behavior that are almost impossible to disrupt. Danticat shows us characters at their breaking points—a man who has fathered and then abandoned a child in an attempt to deny his sexual orientation, a radio show host who wants to break free of self-righteous domination by her secret lover, a maidservant who finally speaks out about sexual assault at the hands of her employer. Danticat squarely addresses Haiti’s social inequality, drawing rich characters all along the socioeconomic spectrum, showing both how wealth and power allow the rich to escape consequences for their behavior, and the fact that no amount of privilege can insulate people from their grief and pain.

Resisting sentimentality or oversimplification, Danticat creates a series of stories that weave seamlessly into each other, each story answering questions conjured by those that precede it. The narrator is a trickster of sorts, jumping through years as if they were puddles, filling in the ten-year span between when one of Ville Rose’s wealthiest sons leaves for Miami and returns, prodigally, on the eve of Claire’s seventh birthday and the occasion of her running away. As with her previous collection, The Dew Breaker, Danticat delivers on the promise of the novel-in-stories, succeeding where so many authors falter, at using the form to deepen our understanding of characters by showing them to us in varying contexts and from different perspectives.

My one quibble is with the ending, where the writing seems to slip in and out of focus as we witness Claire’s wrenching decision to run away or return to Ville Rose. While this is useful for creating suspense and building tension, the book’s last story seems to suffer from its disjointedness. This is a small concern, however, and doesn’t subtract much from a book that is masterful overall.

Published on March 17, 2014