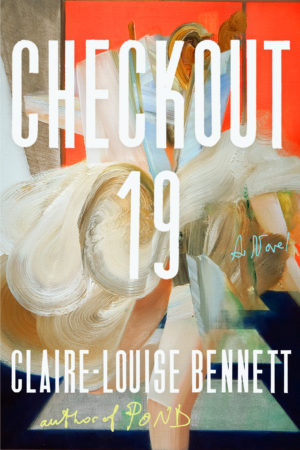

Checkout 19

by Claire-Louise Bennett

reviewed by Lily Rockefeller

Although its cover assures us it’s something decidedly normal and comprehensible—a “novel”—Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19 eludes definition. Wild, refreshing, and delightful, this much-anticipated collection of vignettes is the disorienting but worthy successor to Bennett’s stunning debut and surprise hit Pond.

Reading Checkout 19 feels not so much like listening to someone recollect stories from her life as watching her reminisce from within her own brain. From the dim chamber of her mind, we know little of that person, except that she is a youngish woman from southwest England now living in Ireland who is very, very interested in books. We are introduced to her in the first few pages with a breathless, almost impatient description of her early experiences reading:

That’s right. We could sit for a long time couldn’t we with a book beside us and not even open it. We certainly could. And it was very edifying. It certainly was. It was entirely possible we realised to get a great deal from a book without even opening it.

Thus are we introduced to a life lived half in reality and half in the imagination, literature, and misty realms of self-reflection. Much of this story is about stories, as Bennett’s perhaps quasi-autobiographical narrator immerses us in a retelling of the short fiction she’s written, expounds on the literary criticism of Anaïs Nin, and listens for echoes of A Room with a View while visiting Rome. It is apt that the book opens with a quotation from Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina, a novel just as obsessed with crafting a self through language as Bennett’s is. As much as the book is about art, it is also a book about a life, and the way the two are bound up with each other.

Bennett’s greatest talent is her precise prose. She captures exactly, for example, the narrator’s terrible mix of fear and pride in an emotional tug-of-war between friends: “His mood would blacken tighten harden and he’d stand there with heels dug in daring me to pit myself against him. And that amused me too, in a malign sort of way that was fearsome to endure yet impossible to overthrow.” It’s her precise turns of phrase that make you think, I don’t know why I get it, but I get it.

Fans of Amy Leach’s quirky essay collection Things That Are and Eley Williams’s Attrib. and Other Stories and will be lucky to find another collection just as unusual and inspired as those. And if Checkout 19 lacks their affable lightheartedness, the narrator’s neurotic eccentricity doesn’t make her aloof. Even as she knows she’s probably smarter than most people she meets (you’ll learn some vocabulary words along the way), it’s clear she’s had a lonely upbringing and her sensitivity and vulnerability have followed her into adulthood.

Just like its narrator, however, Checkout 19 is more audacious, and for that reason less relatable, than the already delightfully obsessive and inward-looking Pond. As with her first book, Bennett captures with astonishing clarity the beautiful, Woolfian minutiae of subjectivity that so often escape notice, and which were such a delight to behold in Bennett’s first novel. But if Pond seemed prone to navel-gazing, Checkout 19 whisks the bewildered reader into the narrator’s flights of imaginative fancy without apology. Some household tragedy echoes briefly in the book—a mother’s death? a divorce?—but is never addressed, and a brother appears only in the last few pages. With a lesser author, these decisions would easily be classified as faux pas. However, Bennett takes the rule book and pulps it—she knows exactly how to land us smack-dab into the harsh exactness of reality when a traumatic incident takes place in the final vignette.

Overall, Bennett is writing against the immensely neat books that you trust are saying something very profound if you only cared to figure it out. Her attempt, above all, is to capture life as it happens, not as we try to make sense of it later on. At times that means that we descend deep into the narrator’s unconscious and catch something of which not even she is aware. This utterly strange quality makes the novel an extraordinary exploration of selfhood and self-expression, one that argues for the centrality of literature to our lives.

Published on July 12, 2022