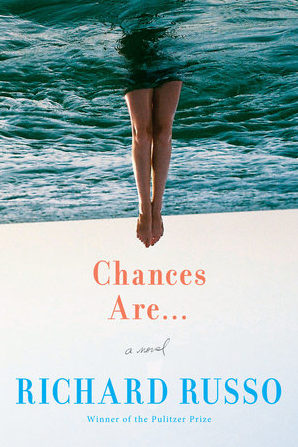

Chances Are . . .

by Richard Russo

reviewed by Erik Hage

Richard Russo’s Chances Are… is about three male friends in their mid-sixties who first met as undergraduates at a small liberal arts college in Connecticut. Back then, they weathered the Vietnam draft and the disappearance of their friend Jacy, a wealthy and wild young woman who vanished shortly after graduation. All three were infatuated with her. In many ways, they still are.

The book moves between the perspectives of the men. Lincoln Moser is a financially struggling Las Vegas real-estate broker whose wife seems to do much of the adulting for him. Mickey Girardi, a Harley-riding rocker in a bar band, is a man-child with layers of violence simmering underneath his playful, ne’er-do-well exterior. And Teddy Novak, the most complex and fully realized of the three, has until recently been the editor of a small academic press specializing in religious texts. A strange childhood and a high school basketball accident have left him nursing psychic and physical wounds and forced him into a monastic existence.

Now, more than four decades later, Lincoln, Micky, and Teddy have returned to Martha’s Vineyard, the setting of Jacy’s disappearance, for one last hurrah before Lincoln sells his family home. At first, the mystery of Jacy merely laps round the edges of the narrative. When it does finally seep into the novel’s center, rather than produce a sense of urgency, it seems to intrude upon what really motivates the novel: the complicated, unconventional crosscurrents of relationships. Russo is not trying to write a straightforward mystery, but his lack of interest in either following or meaningfully departing from the conventions of the genre means that the mystery component of the novel sits uneasily alongside his more psychological interests.

Russo has been lauded over the years as a renderer of small communities, particularly in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Empire Falls (2001) and in Nobody’s Fool (1993). But even when writing about small towns in Maine and upstate New York, his true mastery lies in the ambiguities and mysteries at the heart of relationships, particularly those of the aged and experienced. For example, this revelation comes in a conversation between Lincoln and Teddy:

“What’s interesting,” Teddy was saying, “is that people aren’t more curious about each other.”

“Don’t we all have a right to privacy?”

“Absolutely. But that’s not what I’m talking about. We let people keep their secrets but then convince ourselves we know them anyway.”

This is a novel at once wise and world-weary, with so much of the action occurring in memory, and with the men’s original youthful perspectives having hardened into a zen-like acceptance of one’s lack of importance in the warp and woof of existence. As Russo writes,

Forty-four years ago, on this very island, with mountains of evidence to the contrary staring them in the face, Teddy and his friends had all agreed that their chances were awfully good. Sure they were fools, by any objective measure, but hadn’t they also been courageous that night? What were people supposed to do when confronted with a world that couldn’t care less whether they lived or died? Cower? Genuflect?

Russo’s characters aren’t highly articulate, but in their earnestness and constant questioning, they grapple with mysteries of a kind very different from that of Jacy’s disappearance: What does it all mean? Why do we suffer? How did we become the person that we are?

By moving back and forth through time, Russo gives us a sense of the characters’ larger evolution. By the end, we know them so deeply that each man seems to contain a world. Yet Russo’s brisk, immensely readable prose sweeps us along, raising complexities while never getting bogged down by them. It’s a sleight of hand in which he counters heavy ideas with a light (even wry) touch. For example:

To Teddy’s way of thinking—and he’d thought about it a lot—this depended on which end of the telescope you were looking through. The older you got, the more likely you’d be looking at your life through the wrong end, because it stripped away life’s clutter, providing a sharper image, as well as the impression of inevitability. Character was destiny.

While we eventually learn what happened to Jacy, the larger questions of the characters’ lives—of life itself—remain unresolved. But Chances Are…is ultimately, if quietly, uplifting. We see how acceptance overcomes resignation and regret, and how, in the course of this, men forged in an earlier era free themselves from a “peculiarly male conviction that silence conveyed one’s feelings better than anything else.” And here Russo pulls off another trick: finding redemptive light in so much sadness and acceptance.

Published on October 22, 2019