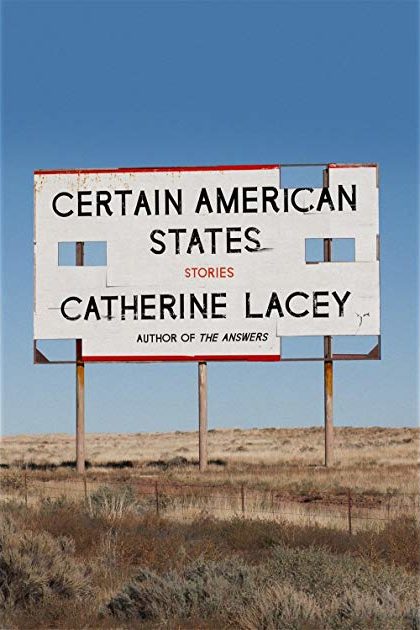

Certain American States

by Catherine Lacey

reviewed by Chelsea Bingham

If this collection were guided by one principle, it would be something the narrator of “Family Physics” says at one point: “I remembered or thought for the first time that when anyone tells a story they must leave most of it out [ … ].” Catherine Lacey has a way with words, which previous readers of her work will recognize from her novels, Nobody is Ever Missing (2014) and The Answers (2017). With Certain American States, Lacey tries her hand at short stories, and meets with some success.

In each story, there is a great deal that has been left out. There is something of Hemingway in this—in Death in the Afternoon, he writes, “If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them.” By leaving things out, Lacey has distilled an eerily realistic vision of what it’s like to live and relate (or not) to those around us, but she has done more than give a feeling of things she might have said.

The empty spaces, the omissions, are deliberate. Many of her characters’ lives take place in silence or in their heads. In “Learning,” one remarks, “This silence, I thought, could choke a person.” In “The Grand Claremont Hotel,” another advises, “what a person should remember at times like these, when all normalcy seems to have left you, is that all things begin and end in the mind.” And in “Because You Have To,” the narrator confesses: “I have thought often of what it would take to kill a cat, quietly and quickly, with my bare hands. I have thought of this often. In fact I am thinking of it right now.” We are privy to some of the darkest thoughts of these characters, but not always their backstories. In Lacey’s hands, life, and the stories we tell about it, just aren’t that simple.

In “The Four Immeasurables and Twenty New Immeasurables,” the narrator fails an internet quiz about discerning emotion in human eyes. She can no longer “look at anyone without a list queuing up—A. Trusting, B. Hesitant, C. Happy, or D. Confused—and even though E. All of the Above was never an option I’m still not convinced anyone could ever be that simple. One feeling at a time.” For the most part, her characters are people just trying to get by. When looking for answers all they find are realities far more complicated than they could have imagined. The same narrator, trying to discern the truth behind a girlfriend’s disturbing behavior (“The German was nearly arrested for jumping on a Chihuahua on Seventh Avenue, breaking its back, taking its life. An accident, she said [ … ]”), reflects, “[ … ] it was just as hard for me to believe her as it was hard for me to believe how hard it was for me to believe her.” Reality, like the truth, is as distorted by the listener as the person telling the tale.

Isolation is ever-present, whether it’s shown through a young woman running away from her family (“Family Physics”), a lost cat (“Small Differences”), or a man who cannot be understood (“ur heck box”). In the title story, the narrator recalls her godfather telling her, “The loneliness of certain American states is enough to kill a person if you look too closely—”. Some of these states—grief, anger, emptiness, estrangement, loss—are highlighted more than others. Happy endings are not to be found, but Lacey makes up for this with clever sentences, dark humor, and cynical realism: “You only learn who you’ve married after it’s too late, like one of those white mystery taffies you have to eat to find the flavor, and even then, it’s just a guess.”

At times eerily prescient, at others puzzling, you will want, and probably need, to read these stories more than once. Though they lack the addictive readability of her novels, they give good reason for pause and reflection, taunting, like the mother in “ur heck box,” “Don’t you have anything you’d like to say?”

Published on April 11, 2019