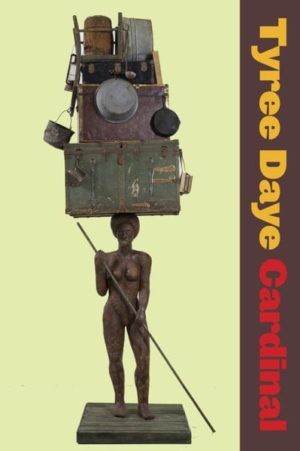

Cardinal

by Tyree Daye

reviewed by Lesley Wheeler

Tyree Daye’s second poetry collection, Cardinal, begins with two epigraphs. From The Green Book, an annual guide for Black travelers in the US during segregation: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published.” And from Nina Simone, from “Chilly Winds Don’t Blow”: “Going where they’ll welcome me for sure.” Both resonate with the description on the book’s back cover, which characterizes Cardinal as “a guide through the particular history of traveling in America as a Black person.” These spare, elegiac poems also root their journeys in North Carolina, the landscape and family that Daye’s words mourn lovingly. Maybe all travel poems are also meditations on home, but this paradox seems acutely true in Cardinal. Red wings flash though the pages, suggesting the need for flight, yet this beautiful book is deeply grounded, defining territory as birdsong does.

Birds call in characteristic repeated phrases; Cardinal is punctuated likewise by recurrent elements. Many of them are visual, such as the family photographs interspersed among verses, not so much illustrating poems as reverberating among them. They portray actual relatives; however, without captions or credits, their moods are most salient: a smiling family in pine woods; a woman cherishing a baby; blurred foregrounds that emphasize off-center people in moments of relaxation or joy. The photographs contribute to the book’s intimacy, the sense of someone remembering a lost world across expanses of space and time.

A recurrent image in Cardinal is the “field,” often referring to agricultural plots in and around Daye’s small-town home of Youngsville in “the flat land of eastern North Carolina.” These fields are also burial grounds—“tracks all over America have bodies under them”—as well as spaces in which a child can daydream about other futures. The present-day speaker lives, after all, far from that soil as he reimagines it. In “When I Left,” he calls himself “fieldless and far gone.”

Daye maps the meanings of the word “field” most fully in the book’s opening and closing sequences, “Field Notes on Leaving” and “Field Notes on Beginning.” Many poems in Cardinal refer to the act of notetaking, but field notes in particular suggest scientific distance, as if Daye were a researcher jotting cool observations. They also evoke Charles Olson’s formulation, in “Projective Verse,” of the page and poem as “fields,” although Daye doesn’t include Olson among his many literary echoes.

Both “Field Notes” poems dance across the page, using white space and printers’ ornaments to suggest lonely searching across great territories of land and sky. “Field Notes on Leaving” juxtaposes a reference to escape from slavery—“the North Star is irrelevant”—with the sense of possibility opened by President Obama’s election. These moments then collide with getting hassled by airport security, obligations to family, and the observation that a Black American poet “can’t afford to think like Whitman / that whomever I shall meet on the road I shall love / and whoever beholds me shall love me.” Daye picks up these tensions between escape and confinement in “Field Notes on Beginning,” another fragmentary sequence full of references to North-South migration and, behind those journeys, the trauma of the Middle Passage. The book ends “in the city,” where the author’s family history must be inscribed on his body, since he can’t otherwise bring the dead with him. “I will not see a cardinal,” Daye writes, “so I drew one on my chest / A coop inside a coop inside of me.”

These final lines harmonize Daye’s references to fields, travel, and writing with the title reference to the red-crested state bird of North Carolina. Birds are commonly emblems of spirit, but Daye refreshes the traditional association through an uncanny strangeness that often links the cardinal’s redness to the blood in his body. “The dead / in me are birds,” he writes in “Would You Miss Me?”, adding, “the heart is not a cardinal, it can’t leave on its own.” Blood means family and heritage, and several poems link the cardinal to one relative especially, a “Grandmother Carrie” to whom “Leave Yourself All Over” is dedicated. “Sometimes I want to see you so badly / I dream myself full of the reddest wings,” he tells her, and “I wanted to see you in that wide graveyard as a cardinal.” These images chime with the volume’s final lines, evoking a real or metaphorical chest tattoo of a caged cardinal, analogue to the soul inside the body, the heart inside the ribcage. This inheritance shapes a person inside and out; poetic and musical echoes permeate Daye’s constellations of words.

Cardinals are cheery creatures, bright and noisy, dwelling near people in yards and parks. They defend their territories fiercely and don’t migrate. I kept thinking, as I traced the patterns in this lovely collection, about all the lyric poets who, according to my teachers, represent their temperaments and ambitions through iconic birds: Shelley’s skylark, Keats’ nightingale, Poe’s raven, Frost’s oven bird. For all the literary allusions here—there are many—there isn’t a shred of pretension in this book, and slotting Daye into that white male lineage feels wrong. Yet it’s interesting to think about cardinals as emblems signaling a connection to region, and a determination to stay low, to forage on or near the ground.

The cardinal is also the state bird of Virginia, where I live. I drafted this review as a January twilight gathered and a cardinal’s chipping song pierced the quiet. It wasn’t a bad way to tune my senses to a collection that recognizes the stars without hustling through the literary stratosphere. Cardinal eschews high-flying grandeur, but you will treasure its company.

Published on March 26, 2021