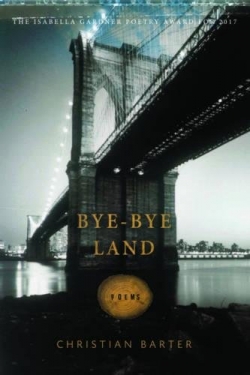

Bye-Bye Land

by Christian Barter

reviewed by Kevin T. O'Connor

Bye-Bye Land, a single book-length poem, represents a departure from Christian Barter’s first two collections of discrete lyrics. Boldly experimental and thickly footnoted, by turns moving, funny and disturbing, the work uses an array of speakers to interrogate the ruined fragments of our American dreams, where contemporary horrors—Guantanamo torture, environmental havoc, healthcare shame, murderous consumer frenzy—are measured against the detritus of our cultural legacy. The expansive social vision and moral ambition of Bye-Bye Land make our ears more alert and attentive to the mélange of voices around us—one from across the kitchen table, another from the television, a third—say, from Keats or John F. Kennedy or an early Native American—welling up from a deeper cultural memory. By employing the quick-cutting techniques of verbal montage, Barter is able to switch scenes and tonal registers with lightning speed and to subtle effect. Early in the book a banal domestic scene cuts to the Elizabethan poet Thomas Wyatt before returning to an almost rhapsodically Whitmanesque poet-narrator:

And we need to stop by the ShopRite—we’re out of milk.

And don’t forget the tank’s about on empty.

Forget not yet the tried intent

Of such a truth as I have meantIn the last part of the night

when the night is an ink spilled into water

and the things of this world have not yet made it back

from being skyline

This reappearing poet-narrator frequently gives way to a series of unannounced and often unidentified voices. Barter’s art of radical, associative juxtaposition—interspersing documentary quotations with poetry excerpts and fictional conversation—has the effect of not simply ironizing, but enlivening and enriching our sense of everyday speech. Such juxtaposition might remind us of the way that Eliot uses allusive complexity and medleyed voices in The Waste Land—but where Eliot critiques the demotic of a culture that has disintegrated from a classical ideal, Barter’s stylistic method and ethos are quite different: he embeds recondite literary references in order to highlight the gap between high culture and exigencies at ground level. One of his everyman street talkers refers to his own effort to show

… a poem

trying to exist in the real world, which it can’t—

don’t ask me why

Another riff—a commentary on Jdimytai Damour, the Walmart employee run over by frenzied Black Friday shoppers in 2008—is delivered through the voice of a reductively insensitive character:

Jat Jamma? I don’t know, some grass hut name.

They ran right the fuck over this guy.

Can you imagine? Getting trampled to death

by fat chicks trying to save two bucks on a vacuum?

Moving among such personae, Barter is able to disperse his satiric targets, resist sentimentality, and keep interpretive possibilities open. The first section, “The Warm Land,” quotes the Native American chief White Eagle upon being shown his new reservation lands—and his ghostly voice becomes witness to the depredations of our landscape:

We passed by the projects of the Quickie Marts

and we wound through the looping miles of suburbs

where every house and hairdo looked the same

Another darkly comic allegorical voice surfaces from the collective American unconscious to dramatize how environmental pillage is linked to the legacy of slavery and the exploitation of immigrant labor:

And I’m going to need more labor, boss—

these slave ships, they a drop in the bucket, boss;

I need Chinese, Irish, Japanese,

and whatever you can get from Mexico, boss.

We got diggin’ to do, and cuttin’ stuff down,

and blowin’ stuff up, and settin’ stuff on fire.

Images of America’s original sins accrete against the poet-narrator’s transcendental longings. The second section, “The Meaning of Being Numerous,” moves from the poet-narrator’s odal celebration of humans as social animals—opening with the apostrophe, “Brilliant city!”—to an urban everyman railing against the pompous insensitivity of New York aesthetes:

Oh, they got all this stuff here figured right out.

It’s all “this period” and “that period,”

and the “use” of this, and how “bold” somebody was.

“That was bold,” they say, going after the chin.

“That was a bold use of color.” “What a bold line! ”

I tell you what—if drawin’ on some paper? Is bold?

Bold. You’d think with all these geniuses

this wouldn’t be such a fucked-up place to live.

I’d like to round up all these geniuses

and say, Now how come all this killing is going on?

Or as a similarly skeptical speaker would have it: “poetry makes nothing happen … dudes.”

The scope and field of Barter’s explorations widen throughout the volume. In the third section, “And All the Lives to Be,” he takes on the problem of America’s future through the 2007 death of Edith Rodriguez, who bled to death as her desperate boyfriend called for an ambulance to pick her up in a hospital waiting room. The apocalyptic pronouncement of a blogger about Rodriguez’s death furnishes the book’s title:

and then this whole glass house of cards

is going Click Click BOOM to Bye-bye Land.

Closure is a special challenge for a book that opens up so much raw and urgent sociopolitical material, and in the book’s last section Barter again looks forward, giving us another apocalyptic speaker. This time, it’s the tragicomic voice borrowed from Berryman’s Dream Songs, who teasingly evokes the possibility of revelation in modern America:

STILL WAIT’ FOR THE WORD, BOSS

But the book’s final quotation is Amelia Earhart’s last received transmission: her spatial coordinates, which are followed by silence rather than a promised Word. Readers are left with the evidence of Bye-Bye Land itself—ultimately a moving elegy for our collective dreams.

Published on March 23, 2018