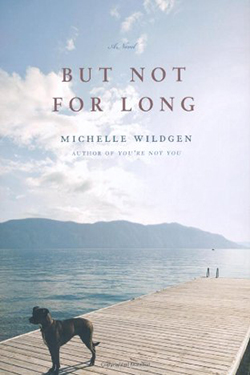

But Not For Long

by Michelle Wildgen

reviewed by Elizabeth Greenspan

Greta, the newest member of an organic-food cooperative at the center of Michelle Wildgen’s observant, compassionate, and gently wry second novel, But Not For Long, does not quite fit in her new environs. She has moved to the earthy Madison, Wisconsin, neighborhood to escape a broken marriage rather than to enjoy the benefits of group dinners and CSAs. She is skeptical of the housing cooperative way of life and, most enjoyably for the reader, she is not afraid to defend her bourgeois bona fides when they come under attack.

“There’s a serious community over here, Greta,” the hippie host of a so-called welcome party patronizingly tells her in the novel’s first pages. “It takes some time to get used to, I imagine. It’s more than just buying bulk at Whole Foods.”

Greta dismisses her host as living in a fantasy world with an empty IRA account and is, in turn, promptly accused of being “boojie.” Greta then proceeds to silence the room.

“Who are you, Abbie Hoffman?” she asks. “I never even understood why ‘boojie’ is such an insult. Oooohhhh, I’m middle class. Stop me before I send my kid to an excellent state school and donate to Planned Parenthood.”

Wildgen captures the tensions and proclivities of her progressive enclave with a knowing touch. At the welcome party, everyone proudly displays their “furry” underarms. And Karin, twenty-four, and the younger of Greta’s two housemates, arrives after two disillusioning years with an experimental girlfriend in the “Womyn’s Co-op.” But Wildgen never crosses into full-blown satire. Rather, the fun, finely observed details of co-op living provide lightness to an otherwise contemplative story of loss and responsibility in contemporary America.

The novel follows Greta, Karin, and a third housemate, Hal, over three days as they grapple with the frustrations of a summer energy blackout and, more profoundly, the burdens and freedoms of adulthood. The electricity-less co-op is as much a symbol of the transitional and occasionally dark places in which they find themselves as it is a setting for them.

On the first evening of the blackout, a strange man appears passed out on the porch of their house, vodka bottle in hand. The man is Greta’s estranged husband, Will, who would be a sweet, smart spouse if not for his debilitating alcoholism. Greta had not told her housemates she was married—she also never told her husband where to find her—and Will’s sudden appearance unsettles them all. For Karin and Hal, the slumped-over Will embodies everything they reject. He’s a lawyer with all the material trappings and none of the personal fulfillment of “the good life.” He also represents, even more disturbingly, a deeply held fear: the failure to be a functional grown-up.

Hal, a thoughtful, lonely guy in his mid-thirties who delivers meals to the elderly, takes the greatest interest in Will. The morning after Will’s arrival, Greta and Karin scurry off to their jobs, but Hal cannot bring himself to abandon the still-inebriated Will. Instead, he brings him along to visit one of his food bank charges, a feisty old woman named Mrs. Bryant. Even after a series of embarrassments—Will sneaks off to the kitchen to steal a drink and passes out on Mrs. Bryant’s couch—Hal drives him home and tries to convince the exhausted and angry Greta that Will needs her help.

In her well-received debut novel, You’re Not You, Wildgen explored how disease shapes and plagues a marriage. In that story, a spouse has Lou Gehrig’s disease, another extraordinarily destructive illness. But unlike alcoholism, Lou Gehrig’s elicits an automatic and unconflicted compassion for the character it afflicts. It is a testament to Wildgen’s talent, therefore, that her portrait of Will is both honest and empathetic. He is likeable despite but also because of his failings.

Once Greta leaves him, Wildgen writes, Will survives only through the little things, like a weekly haircut. “It was just a relief to feel someone’s hands in his hair, all the offhand warmth of someone’s fingers at the ears, the cheek, the neck.” In the novel’s final scenes, Will searches for a barbershop open in the blackout; it’s the only thing he can think to do to extend his sobriety of a few hours. He finds one, and with it a brief, calming moment of touch. For Will, and everyone else in the story too, it is a modest but hopeful achievement.

Published on June 20, 2013