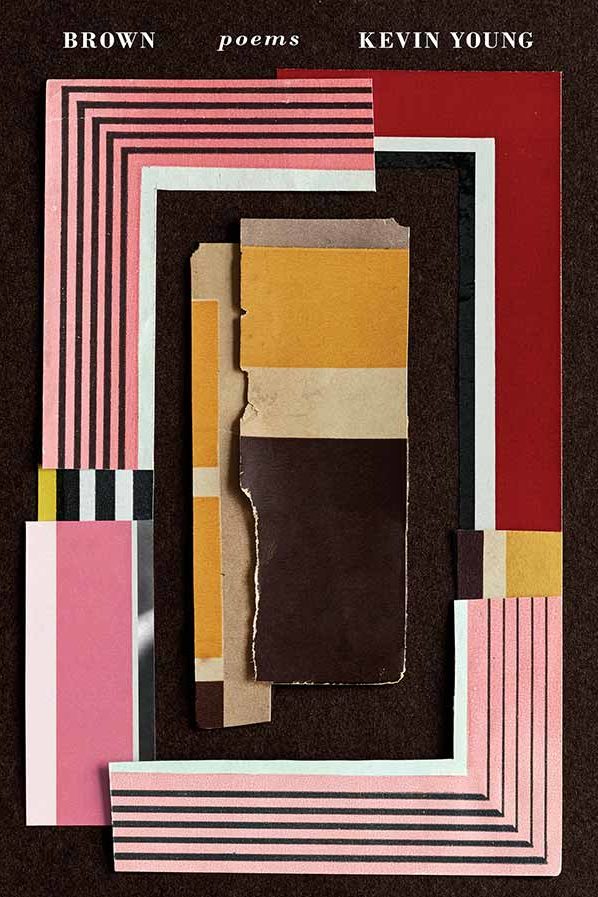

Brown

by Kevin Young

reviewed by Kevin T. O'Connor

In The Book of Hours, his 2011 collection, Kevin Young moved from elegiac responses to the sudden death of his father to reanimating poems on the birth of his son. His new collection Brown reverses the trajectory, beginning with “Home Recordings,” shadowed recollections of boyhood, and culminating with “Field Recordings,” somber reflections on the recurring traumas of African American social history. In its progression toward a more experienced vision, this brilliant and moving collection is structured as a coming-of-age chronicle. Young’s poetry on social issues tempers a tragic sense of outrage with a blues-based ethos which, as Young points out in a recent review of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s We Were Eight Years in Power, is “embodied by the likes of the poet Lucille Clifton or Zora Neale Hurston … [and] sees black life as a secret pleasure, or at least sees joy, however hard-earned, as ‘an act of resistance.’” In these poems, the expression of “hard-earned joy” in the face of unspeakable injustice is an ennobling challenge.

Brown is not just a socially-aware autobiography in verse, but a consciously emblematic exploration of how cultural and historical forces shape personal identity, and how, in turn, the growing consciousness of a poet critiques that formative culture. The title Brown is full of possible associations and meanings. Beyond skin color, it also evokes historical moments and personages connected to race, such as the landmark segregation case of Brown vs. The Board of Education, as well as the violent abolitionist insurrection of John Brown. The fact that both these touchstones took place in Kansas, where Young was mostly raised, provides the poet with invitations to explore the intersection of his personal growth with this regional history. “American Bison” captures such a Wordsworthian “spot of time”:

when we saw it:

John Brown

muraled, arms thrownwide, beard afire, dead

soldiers smoldering

at his feet. Holy me—how to unsee those eyes

wild-wide like a mouth?

Behind him a tornadotearing up the plain—

which would never be

that way again.

Juxtaposing the effect of memorial art with a natural disaster, this passage demonstrates the power of Young’s restrained style: his formal signature of short, tight, strong-stress lines and spare, colloquial diction. His style demands a fierce economy and focus, and rapid-fire enjambments provide torque to the syntax snaking down the page. The opening of “Shirt & Skins,” another early poem about the way the cultural residue of racism seeps into youthful consciousness, exemplifies how Young’s tight lines enhance sound effects:

I was ten when

Mike Smiley, half-Indian,

skinny, brown-skinned,brought the word jigaboo

to school

like lunch, or the flu,fed him by his adopted

white father who said

that’s what we calledthem then. By noon

it was done—everyone

had a name for what had beenbothering them, some

thing utterly human

as hate.

The insistent and surprising internal rhymes, where even the articles, pronouns, and perfect tense verb forms become prominent, point out the wounding potential of certain word sounds. Young’s distinctive voice is characterized by its ability to carry so much weight in so few words, with so much musical motive.

While the scope of Blue Laws (2017), a compendium of his first eight books, reaches back in history to the colonial era Amistad revolt and the Civil War, the time span of Brown is defined by the maturing consciousness of the poet. In “Home Recordings” Young writes enthusiastic tributes to his boyhood sports heroes (Muhammed Ali, the Globetrotters, Arthur Ashe). Later, the eponymous lyric “Brown,” which closes out the early section, poignantly evokes the later adolescent Young on the verge of leaving home, attending services in the same Topeka church where the pastor, Oliver Brown, challenged segregation policy on behalf of his daughter:

The pews curve like ribs

broken, barely healed,

& we can feelourselves breathe—

while Mrs. Linda Brown

Thompson, married now, hymnspiano behind her solo—

No finer noise

than this—

At his best Young invites readers in to feel his sense of lived history. Since “The blues always dance/cheek to cheek with a church,” it is no wonder that his young adult heroes in “Field Recordings” are musicians (Lead Belly, B.B. King, James Brown, the funky fusion 80’s band Fishbone et al). The tour de force sonnet sequence “De La Soul Is Dead” reflects the musically-fueled experimentation, consciousness raising, and all-night partying that is his crucible of adult self-making:

We were black then, about to be

African American, so folks schoolhouse rocked

& smurfed whenever we damn well pleased.

We should have done more, or believed.

The coming-of-age structure of Brown places great weight on its final section where the mature poet, now a father himself, must reflect on our time of reactionary racism and the terrible killings of unarmed African Americans. In his “Triptych for Trayvon Martin”—also dedicated to victims Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, and (one more tragic reference in the book’s title), Michael Brown—Young displays his “refusal to mourn” (“to inter/your name in earth/or to burn back/to bone”) and strains beyond the limitations of the literary elegy:

… splayed

open on a cold table

or left in the street

for hours to stew.A finger

is a gun—

a walletis a gun, skin

a shiny pistol,

a demon, a barrelalready ready—

hands up

don’t shoot—

He dramatizes how, when taken literally, poetic metaphor can resemble the specious rationales of policemen who insist that their shootings of unarmed people of color are justified by the belief that those victims were reaching for guns. “A finger” or “skin” reveals no real threat, but rather conscious or unconscious racism.

The last section of Young’s book is anchored in “repast,” an oratorio for Booker Wright, a Mississippi barkeep and waiter who was beaten and murdered by locals near the site of Emmett Till’s lynching “just for saying/ what’s true.” In “Bass” and other intermittent references, Young implies that his young son—whose drawings decorate the inner covers of the book—may be fated to relive his own journey in Brown, from boyhood memories to his confrontation with atavistic ghosts of racist violence; hence, it is fitting that the poet ends with “Hive,” where a boy naively believes he can carry honey bees from one hive to another without being stung.

Let this boy

who carries the entire

actual, whirring

world in his calmunwashed hands,

barely walking, bear

us all therebuzzing, unstung.

Having contemplated Brown’s searing images of our tragic racial history, readers may be ready to receive the poet’s closing wish like a blessing.

Published on April 11, 2019