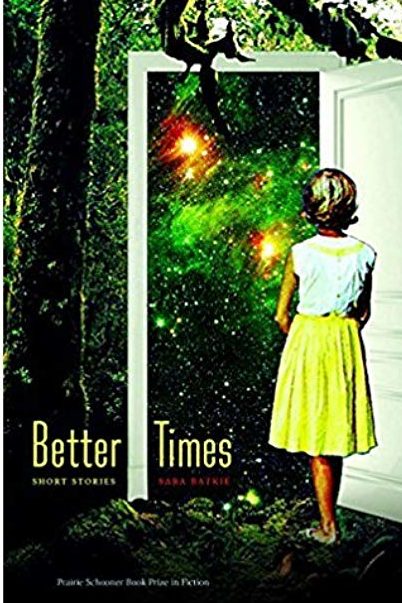

Better Times

by Sara Batkie

reviewed by Leah Marsh

Most of the characters in Sara Batkie’s collection Better Times are missing something: a father, a partner, a breast. The stories that emerge from these absences are starkly beautiful. Each one seems to ask, What is left after something so important has been taken away? Often, what’s left is community, however fractured, and Batkie excels at presenting empathetic portraits of characters struggling to make sense of their relationships with their communities and with themselves.

Take, for instance, the narrator of “Laika,” who looks back on two childhood relationships that influence her even decades later. One is with Babette, a fellow resident of a home for wayward women, who claims to have been impregnated by God. The other is with Laika, the first dog in space, whose story captivated her from the moment she saw it on TV.

Perhaps I have been wrong to think of Laika’s death as a tragedy. After all, if she had been able to return, what kind of life would she be coming back to? A hero’s welcome, surely, but then? A family to take her in? To eke out her remaining years manhandled by some ignorant child, dreaming of another orbit? There was no sorrow in being chosen in the first place, saved from some street-wandering squalor, to be fed and if not loved, then trusted. Some of us are meant to bear the glory that the rest of us merely share in.

Batkie has a talent for taking seemingly ridiculous premises and using them to craft graceful stories with a touch of humor. “Foreigners,” for instance, is narrated by Rebecca, a single woman whose neighbors turn out to be Russian spies. Rebecca’s relationships all seem to be crumbling: she is haunted by thoughts of her ex-husband, her suburban neighbors—with the possible exception of the Russian spies—shun her, and she struggles to connect with her delinquent son, who seems to have a clearer view of her troubles than she does:

“Let me ask you something,” he said. “Do you think you live in this house?” He swept his arm across himself instead of the room. Rebecca flinched and then blushed, knowing she had just given something of herself away.

“Of course I—”

“No,” he interrupted. “You stay here. That’s not the same thing.”

Some stories, such as “Cleavage,” “North Country, Early Morning,” and “Lookaftering,” edge into the speculative, which lends another facet to Batkie’s examination of community in difficult times. “Cleavage” follows a woman who is haunted by her phantom breast post-mastectomy; “North Country, Early Morning” is set in a hospital that’s being robbed, but the robbers seem to know something the terrified hospital staff don’t. In “Lookaftering,” a woman gives birth to a clutch of eggs. One might expect the story to focus on the apparent absurdity of a human woman laying eggs, but Batkie instead centers the narrative on how such an unexpected event impacts the woman’s relationship with herself, with those around her, and with the eggs themselves. “Louisa held the egg up to her ear as if she might hear the ocean in it. But there was just the gentle swell of Wally’s snores,” Batkie writes.

In the collection’s final story, “Those Who Left and Those Who Stayed,” a large piece of an ice sheet in Alaska has broken off and drifted into the ocean, carrying with it several residents and buildings of a small town. Climate change is never explicitly mentioned, but its shadow looms over the characters as they—with varying levels of success—attempt to come to terms with their new reality adrift on the ocean. As one character reflects:

It had surprised but not alarmed him to wake up one morning floating on ice. Though he did feel bad for the young people, he couldn’t help being delighted at this last excitement of his life. He had expected to drift off into the ether of old age; now he would meet a great and unusual end.

The people of the stories live in the present, facing challenges as they arise rather than dwelling on “better times” of the past or future. Although the stories are separated chronologically into “The Recent Past,” “The Modern Age,” and “The World to Come,” none of these eras seem to offer better times, and the collection leaves one wondering if the possibility of “better times” is, and has always been, nothing more than illusion.

Published on June 25, 2019