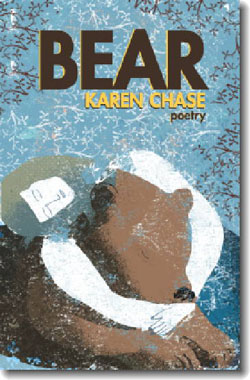

Bear

by Karen Chase

reviewed by John Hennessy

Although many of the poems included here are haunted by an ursine figure, part-criminal, part-courtier, Karen Chase’s new collection, Bear, celebrates a sensual enjoyment of life. These poems are full of action—travel, hiking, deep-sea fishing—yet they are not short on meditation and reflection. Whether she is writing about the Alaskan coast or the Gulf of Mexico, Chase is especially convincing when describing life along the water; she writes as an expert angler and many of her poems involve catching, preparing, and eating fish. But Chase is most powerful in her appreciation of the pleasures of the body, especially of physical love well into middle age.

One of the most striking poems in the book, “For My Son, About to Be a Father,” begins:

Making love last night with

my husband, not

your father, I thought how

sex is a lasting act.

The poem simultaneously affirms her love for her son and releases him from his old role, welcoming him to his new life as he prepares for the new life of his child. Implicit in the title is the fact that Chase’s generational role is also changing. But the poem turns in an unexpected manner—this is certainly no valediction to sexual ardor, nor is it limited to exploding myths of aging. Sex may lead to an individual’s genetic perpetuation, yes, but she’s “not talking about / genes”—she’s talking about the “act,” the way it lasts throughout an individual lifespan and makes “us” last: “we’re all / in this together, it seems.”

In her introduction to Chase’s first book, Kazimierz Square, Amy Clampitt praised the author for her “earthy directness,” admitting that “as one whose work falls in the category of cooked,” Clampitt had “a natural admiration for the raw power of [Chase’s] . . . imagery.” Setting aside Clampitt’s good-natured self-deprecation, I am reminded of J. D. McClatchy’s observations that Amy Clampitt’s own work was “poetry for grown-ups”: she wasn’t “afraid to let you know [she’d] traveled and read books.”

The same can be said of Chase’s work. In “Throwing Away Books,” the collection’s long final poem, the author reduces her life to the essentials—a psychological as well as physical housecleaning—beginning with her library. She decides to retain and reshelve Dante, Gertrude Stein, Hart Crane, and Sappho, but she “jettison[s] great books recommended by friends / that I tried to read but—my problem—could not” as well as “all borrowed books / lent by people who have died. / Gone The Voice of Neurosis. / Gone Bike Tours of Holland.” She calls parting with books lent by her late friends a “recipe for unadulterated guilt,” but she chucks other books with enthusiasm: “Gone The History of Hadassah, / hasta luego my Pavese novels, / . . . finito my study of Italian many moons ago . . . / Moliere? Sorry, Frenchie.”

Chase’s poems of travel share this alternating mode of gravity and comedy and document time in Alaska, Mexico, and Italy with exceptionally precise imagery. “Sanatorio Serbelloni” offers an abundant landscape by day: “Cherries drop across the road. / Blue salvia everywhere—two days ago / Italian snows steamed into a mountain town.” But later she’s overwhelmed by the “fragrance of rosemary hedge,” and once “old night” arrives, she finds herself in “drifts of girlish paralysis,” fearing the loss of her father, remembering her own childhood struggle with polio and her mother’s early death. In “Striper,” she and her husband weather a storm during a fishing trip by going to bed together: with “white caps spraying our / shack, tide lashing in, we made a // lot of love the day and night before.” But Chase may be most observant, most painterly, when describing the far north:

I look down at the ground,

at the tiny yellow cinquefoils,

at the campions, the cotton grass,

I look out at the great white massifs,over to the exploding river, gunmetal

grey from glaciers, out at the green

tundra where you wander unnamed streams.

Bear, I belong in my yard, worrying

about words and money, acting human.

Even Chase’s poem for her mother who died young, “Federico Fellini’s Birthday,” has a convivial lightness of touch, surprising and oddly charming in an elegy. On learning that the late director and her mother shared a birthday, Chase writes, “You’d both be surprised / how the world’s changed. Dad’s okay.” Soon Dad and his new wife—“who is younger than me by far”—will be traveling to India. Would Chase’s mother be jealous if she knew? It seems unlikely; rather “You’d be amazed how small / the world has become.” If she were able to see Chase’s grandchildren, and especially Ruby Leah, her namesake, she’d “die again, but this time / of happiness.”

While this is certainly “poetry for grown-ups,” Karen Chase’s poems are buoyed by lightness and vitality, a joy in physical pleasures, and an inimitable sense of humor, traits that make her poetry—and the prospect of being grown up—satisfying and natural.

Published on March 6, 2015