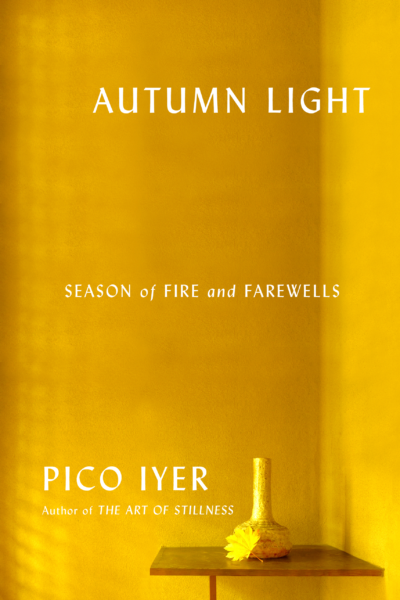

Autumn Light

by Pico Iyer

reviewed by Laura Albritton

Pico Iyer’s new memoir, Autumn Light, opens with his wife, Hiroko Takeuchi, unexpectedly calling from Japan to say, “My father now hospital.” On the next page, we learn that the writer is still out of the country when his father-in-law dies. Iyer, born in England and partly raised in California, has written much-loved, beautifully constructed works such as Video Night in Kathmandu and Falling Off the Map. In this new book, he contemplates aging, death, family, and Japan, where he has lived part-time for decades. Early on, he explains the title of the book: “Autumn poses the question we all have to live with: How to hold on to the things we love even though we know that we and they are dying. How to see the world as it is, yet find light within that truth.”

Finding “light within that truth” proves to be difficult, particularly when his mother-in-law starts declining mentally, and his own mother, in California, grows more fragile. In the Japanese suburb Iyer calls home, even his leisure activity—playing ping-pong at the local rec center—offers intimations of mortality, because his elderly fellow players undergo their own struggles with aging. While his wife performs rituals as she grieves, Iyer confesses that religious rites hold little comfort for him: “I’ve never been a great one for belief, or for trying to put words to what’s beyond us.”

As much as Autumn Light recounts Iyer coping with mortality, it also chronicles his wife’s response to loss. Hiroko finds meaning in traditions: during the Buddhist celebration of O-Higan, the days surrounding the autumnal equinox, she makes a customary visit to her grandmother’s gravesite. Afterwards, she tells her husband, “I so happy talk my grandma.” Her matter-of-factness and familial connections contrast with Iyer’s more abstract musings, tinged with melancholia: “We’re so convinced we’re moving forwards, when all I seem to do is go round and round with the seasons, certainly no wiser, and often only more sure of how much I cannot know.”

There is a remarkable ease to Pico Iyer’s liquid, conversational prose, as when he writes, “I’d moved to Japan, I thought, to learn how to live with less hurry and fear of time [ … ] to learn how best to dissolve a sense of self within something larger and less temporary.” Even his spoken dialogue consists of well-crafted sentences. When Hiroko is quoted, however, the language is abrupt and simple. “I cannot shrine this year,” she says, and, “Summer little ending. Now come autumn.” It is unclear whether we are meant to understand that the couple is speaking English or Japanese; in another book, Iyer writes that he seldom speaks English in Japan, but here, he suggests that they converse in his own tongue: “Japanese has only two tenses, and in Hiroko’s homemade ideogrammatic English, things grow doubly conflated, especially as she’s more comfortable in present tense than past.”

Although he is the foreigner in Japan (and not fluent in Japanese), it is Hiroko, with stilted, sometimes ungrammatical speech, who comes across as the outsider. Writers of fiction from Pierre Loti to Graham Greene have grappled with how best to convey the conversation of non-native speakers of their own languages. Sometimes these fictional portrayals are unflattering, for the obvious reason that the native speaker sounds—and therefore appears—superior. When a real person is put at a linguistic disadvantage in a text, are there similar (in this case, unintended) consequences? Perhaps. One wonders if a verbatim transcription is always the best approach.

Due in part to her linguistic representation, and in part to her overall portrayal, Hiroko remains something of a cipher. At one point, in describing her devotion to cleaning house, Iyer notes, “but of course it’s Hiroko’s deeper cleanliness—her freedom from second thoughts, from the need to gossip, for malice or the hunger for complexity—that is one of her sovereign gifts.” Herein lies a conundrum for Iyer’s devoted readers: they read his books precisely for his hunger for complexity. Yet how to get across the attractiveness of this other way of being, Hiroko’s way, so that the reader may also appreciate her virtues and come to feel something for her? The portrayal seems stuck on the surface, the surface of Hiroko—and by extension, Japan.

The book grows more intimate, interestingly enough, in passages about the couple spending time with the Dalai Lama (whom Iyer has known for years). When Hiroko confides to the Tibetan, “I want to tell you: my father passed away this year,” the Dalai Lama asks questions, then “steps forth and holds her for a long, long time.” The scene and Hiroko herself suddenly become more accessible and relatable.

In other works (the recently published Japan, A Beginner’s Guide to Japanese and the 1991 book, The Lady and the Monk), Iyer delves with great authority into the complexities of Japan and its people. Why the marked difference between those works and Autumn Light, which seems less capable of moving beyond the surface? The disparity might occur because Autumn Light was written out of grief, possibly the hardest emotion to convey with visceral accuracy, particularly as one phase of grief is numbness.

With its episodic structure, Autumn Light is thought-provoking and poignant, if not entirely cohesive. In the final pages, describing the manuscript to Hiroko, the writer says, “Not so much story.” She asks him, “Your book, nothing happening?” To this, he replies, “Well, not exactly nothing. But what happens is not so visible. It’s hard to see which parts are important until years later. Or maybe never.”

Published on November 25, 2019