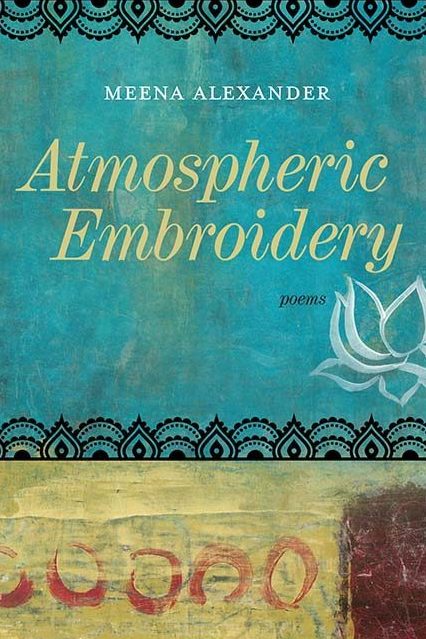

Atmospheric Embroidery

by Meena Alexander

reviewed by Carmen Bugan

Meena Alexander’s wide-ranging collection Atmospheric Embroidery raises important questions about how much poetry can help us to understand the suffering of others. Alexander, who died at the end of last year, was born in India and lived in America for the last quarter-century of her life, but she also spent time in several other countries, including Sudan and England. One of the best-known Indian poets in America, Alexander made her mark by writing about dislocation and transformation of body, history and experience; she also published novels, criticism and the memoir Fault Lines.

In a 2005 interview in the Kenyon Review, Alexander spoke of her belief that “In a time of violence, the task of poetry is in some way to reconcile us to our world and to allow us a measure of tenderness and grace with which to exist.” Atmospheric Embroidery answers this call but not without showing the limitations of the lyric and of language as it engages with the world’s horrors. In “Night Theater,” she laments “We have no words / for what is happening.” The speaker in the poem “Fragment in Praise of the Book” suggests that the “Book with the word for love / In all the languages that flow through me” is also the “Book of alphabets burnt so the truth can be told.”

In particular, Alexander questions the ability of language to represent incoherence and brutality. In the impenetrable “Chilika Lake,” where girls “will float in the warmth of lake water / Gone to hell for love, nothing but” and where a village is a scene of “carnage of crows / Hurried betrothals behind cheap mauve curtains,” the past is seen as “Festoons of words no one believes.” In “Last Colors,” a nameless, genderless child draws pictures of a father who lies in Khartoun with his hands and ears torn, and of a “woman with a scarlet face, / Arms outstretched, body flung into blue.” Alexander creates a nightmarish world where the violence that the child draws has clear and lush representation in the poem, but where there is no representation of the child who has witnessed it all. In a similar vein, “Last Colors” is part of a cycle written in response to drawings made by children from Darfur living in relief camps on the Chad border. The cycle’s opening poem, “Sand Music,” speaks in the voices of the camp children, who in turn speak for all people dislocated by unimaginable violence: “We do not know who we are or what songs we might sing.” In this line, Alexander points again to what is left unvoiced and unpainted, and calls into question the power of art to witness. The poems do not imagine the faces, the features, the names of the children whose drawings have inspired their existence. The reader sees the horrors, but not the individuals experiencing the horrors. Is this an acknowledgement that we cannot ever imagine the lives of those oppressed, an act of humility in the face of suffering many of us will not know?

Yet in another poem, “Nurredin,” we do have a child speaking in the first person, naming himself, urging the reader to “Remember me, Nurredin / My name means light of day.” Even as language falters and fails, the speaker of the opening poem tells us “An invisible grammar holds us in place.” Alexander creates her own grammar, which holds past and present in three continents, and places personal stories of love and loss in a conflict-riven world. “The Journey” is a beautiful indication of how language and experience come together to show the complexity of the poet’s work:

The journey was awkward: lines blown inward, syllables askew.

Gulls nestled in torn pages.There were many languages flowing in the fountain

In spite of certain confusion I decided not to stay thirsty.

Atmospheric Embroidery also contains poems about the “periodic pleasure / Of small happenings” as in “Darling Coffee” in which the language is luxurious and tender, creating cherished moments of togetherness away from “the brazen world.” Here a sense of inner peace, and the natural flow of time are still possible:

Let’s find a room

With a window onto elms

Strung with sunlight,

A café with polished cups,

Darling Coffee they call it.

May our bed be stoked

With fresh cut rosemary

And glinting thyme,

All herbs in due season

Tucked under wild sheets

Fit for the conjugation of joy.

In her opening poem, “Aesthetic Knowledge,” Alexander reminds us that “We are creatures of this world” and that, as we paint the world and draw colors from it in order to paint ourselves, “landscape becomes us.” This poem seems to say that art is born from the world and it transforms us. This is a strong collection that is by turns confident and questioning, and equally engaging in both modes.

Published on April 11, 2019