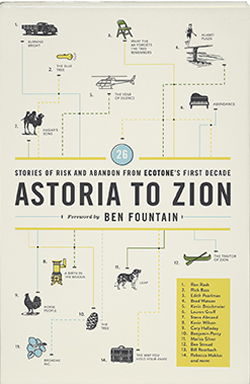

Astoria to Zion: Stories of Risk and Abandon from Ecotone’s First Decade

foreword by Ben Fountain

reviewed by Mark Chiusano

“Broadax Inc.” by Bill Roorbach, an excellent story out of many excellent stories in Astoria to Zion, begins with the brash inventive voice and language that are the trusty weapons of short stories: “My old champ and pal ‘Frederick’ Duk Nuhkmongamong simply appeared in my office—first sign of trouble, no phone call.” The author assumes that you will orient yourself as to place and time, and quickly begins to spin his zany narrative—the fall of shark-like businessman Mike Broadax (“They’d find license plates in my gut when they finally croaked me, whole propellers from ships”) at the hands of his old friend Duk, after Broadax’s flirtations with Duk’s wife.

It’s a revenge story as old as time, but there is a layer, too, of current anxieties. Duk is a whiz-kid hacker, who through digital and other manipulations manages to destroy Broadax’s business, financial stability, and general way of life. In the end, Duk has everything, though Broadax gets the girl, and we leave the new couple on a beach somewhere in Hawaii, “that eccentric old surfin’ couple with the deep tans and easy laughs, grass skirts, floppy hats, Jimi Hendrix on the borrowed iPod.”

There is a certain digital anxiety being acted out in this collection of fiction from Ecotone magazine’s first decade, as well as a feeling of urgency, as if the need for a short story must be argued for here and now, guided by Ecotone’s mission to reimagine the idea of place. As Ben Fountain argues in the book’s foreword, “In an age where place has never seemed more tenuous and abstract, it’s hard to conceive of a more relevant mission for a literary magazine.” We live in an exciting, pulsing world of screens, allowing us to connect with strangers from Jakarta, watch videos while hunkered down on Siberian tundra, or read this very review in the comfort of home. The stories in Astoria to Zion recognize and struggle with the draw of the screen, which makes them all the more interesting and timely.

The best of these stories succeed by doing most purely and exactly what a story does best. There are the slow pleasures of masterly writing here, in Brad Watson’s family drama, “Alamo Plaza”; Lauren Groff’s tender end-of-life adventure, “Abundance”; and Cary Holladay’s quiet but stunning “Horse People.” There are sharp satires, like Karen E. Bender’s political send-up, “The Candidate”; and wickedly, darkly ironic stories like Stephanie Soileau’s “The Ranger Queen of Sulphur,” which brings the reader to dead-end Sulphur, Louisiana, where two overweight siblings escape into a video-game world; or the always brilliant Steve Almond’s “Hagar’s Sons,” which takes business analyst Cohen to a strange land of sheiks and deadly plots, unwanted prostitutes and camel races, getting darker and darker as the story progresses. There are stories that make their argument for attention through experimentation, like Brock Clarke’s war story, “Our Pointy Boots,” which describes the homecoming of a platoon of soldiers through a collective chorus fixated on their boots; or David Means’s timeless, placeless narrative of hunger, rambling, and storytelling, “The Junction.”

The stories that joust best with the digital competition might be the selections of historical fiction. The idea of “setting” feels so much more solid, so much more all-encompassing when the story takes place in the past. And there is no purer form of literary transportation than a story that acts as a time machine, whisking the reader away from computers, social media, the thrills of instantaneous connection. I would venture to say that the historical fiction short story is the best of its extended genre—stronger than a historical movie or TV show, which has to struggle with costumes and backdrop, where a single historical inaccuracy ruins the illusion. Stronger too than the historical novel, which can leave us marooned for too long in the safe past, where once-mighty struggles can feel careful and righteous, only reminding us how much better the present has become.

George Makana Clark’s “The Wreckers,” an epistolary love story narrated by a nineteenth-century soldier of fortune who finds himself working on a slave ship, provides a good example. The façade of reality never falls, even as Clark conjures up a strange, antique seaside world. The love story is nimble and strange, both clever and poignant. And there’s no need for a happy ending, no need to drag things out. I’ll avoid the spoiler here to preserve the reading experience—no matter where or in what form it happens, digital or not.

Published on February 11, 2014