Aster of Ceremonies

by JJJJJerome Ellis

reviewed by Jeffrey Careyva

In Aster of Ceremonies, JJJJJerome Ellis bestows a bounty of lyrics, chants, documentary poetics, poetic prose, and the luscious names of many plants upon us. Ellis’s voice is soft but spellbinding as they navigate the different flows, flowerings, and forms of awareness that their firsthand experience with stuttering provides. Rather than invoking the shame we stutterers are often made to feel, Aster of Ceremonies reimagines dysfluent speech as a blooming cornucopia of new possibilities for unknowing what we think we know about ourselves, those who came before, and the verdant natural world of which we’re a part.

Poems from the first section of the collection, such as “Octagon of Water, Movement 3,” relate the complexity of stuttering to the rhythms of rivers and the silent thriving of plants:

Do not swallow your dysfluent voice. Let it erupt in its volcanic

flowering. Stoppage

thence passage, aporia, Poppy bursting with fragrant seed.

In the printed text, there is a paragraph-sized gap between “stoppage” and “thence” which visually suggests how stopping can make space for something new, how the rhythms that stuttering opens up and takes part in are rooted not just in the mind or the body, but in the movements of the natural world.

The hesitation many stutterers experience when verbally introducing themselves can lead to social anxiety and trepidation. Ellis turns that trepidation into liturgical music:

I’m in line at Shake Shack and I know the cashier will ask for my name once I’ve ordered my hamburger. The liturgy begins in line, my spirit already inhaling the incense of anticipation. How do I prepare? A vector of attention and tension stretches out within me like a taut violin string ready to vibrate. … When the door of my vocal cords closes, another opens. And through that open door I escape into a region I do not know what to call but which is vaster than the space of my body.

From start to finish, Aster of Ceremonies wrestles with names—having one and assigning them to others. Ellis reckons with the fact that a countless number of ancestors’ names are lost to history, and that enslaved people were assigned names at their enslavers’ will. In the longest passages of the collection, Ellis works with two archives: a large grouping of advertisements for “runaway slaves” who reportedly stutter, stammer, or speak with “blockages,” and the intricate encyclopedic descriptions and Linnaean nomenclature for plants in The Flora of North America. Ellis follows M. NourbeSe Philip’s textual practice in Zong! of limiting themselves largely to the language of these advertisements. The collection pays respect to what these ancestors must have gone through on their perilous journey and to the landscape that offered up concealment, food, medicine, and a place to rest.

Aster of Ceremonies continues Ellis’s previous work, begun in The Clearing (2022) and elsewhere, of reconceptualizing our relationship to the stuttering voice and exploring the intricacies of representing speech rhythms through the printed word. While both books explore the fruitful potential of dysfluent speech, Aster of Ceremonies beckons the reader to join its chorus of praise and remembrance. The extended hymn “Benediction, Movement 2 (Octave)” names and exalts dozens of plants in a riveting catalog lined with music:

* We love you, Elder

Virginia Saltmarsh Mallow (Kosteletzkya pppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppp

Pppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppppentacarpos) * We belong to you, Elder Roundfruit

Hedgehyssop (Gratiola virginiana) * We belong to you, Elder Honey Locust (Gleditsia trtrtrtrtr

rtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtrtriacanthos) *

“Benediction, Movement 1” includes a particularly lyrical instance of Ellis’s blooming reconceptualization of stuttering not as a foreign, shameful, embarrassing burden on speech, but as a flourishing root. “Rose” is a name given in one of the runaway advertisements, and also one of the most poetically laden plant names:

the Rose of the stutter

shall GRO

through the fence

of prose

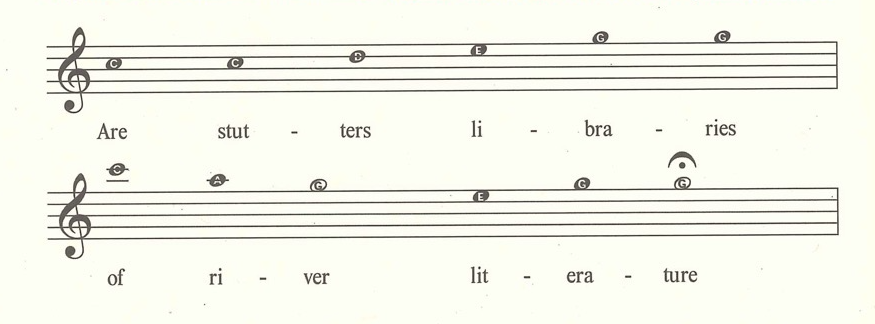

The ceremonies Ellis offers up are far from being esoteric or hermetic. Ellis’s five-part text is full of introductions, footnotes, bars of music, snippets of autobiography, and immaculately etched illustrations of plants, and all of these extra-textual details invite the reader in. A patient and attentive emcee, Ellis teaches us that different members of the aster plant family include daisies, sunflowers, and goldenrods, and also that the heads of many asters are actually collections of many smaller flowers. This figure—of the many blossoming within the one—leads Ellis to ask what it would mean to “aster” a stutter rather than try to master it: “Instead of ‘I speak with a stutter,’ what if I ‘advertised’ to someone by saying: ‘I speak with an Aster. My speech is home to a hundred blooms. These silences you may hear hold more than I could ever know. Thank you for your patience as I pause to admire their beauty.’”

Aster of Ceremonies overflows with the blossoms of plants, the names of ancestors, and the music that stuttering leads us to—if only we let ourselves hear it.

Published on March 6, 2024