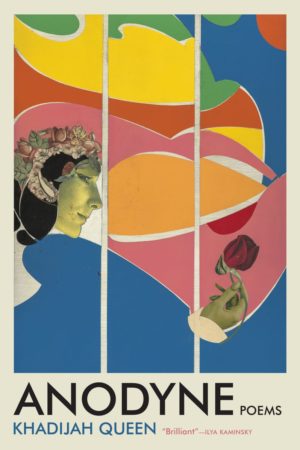

Anodyne

by Khadijah Queen

reviewed by Hanna Andrews

In a 2019 conversation on Rachel Zucker’s podcast Commonplace, Khadijah Queen describes the act of making poems as a celebration of “simultaneity and happening aliveness.” This feels inherent to Anodyne, Queen’s riveting, sixth full-length collection of poems, where everything is indeed happening—all at once—and the reader is led through complex spaces of lived experience: apocalypse and beauty; suffering and persistence; love and its attendant exhaustion.

Just as these spaces contain contradictions, Queen, in Anodyne, reminds us that a body is a monument to simultaneity. As a vessel for our histories (and those of our ancestors), our emotional and physical responses to the present, and our dreams (as well as the dreams of those we love), the body is indeed a site of inheritance. A person accrues and carries myriad experiences across her lifetime.

Anodyne’s opening poem, “In the Event of an Apocalypse, Be Ready to Die” speaks to this:

Repositories of beauty now

ruin to find exquisite—untidy, untended loveliness of the forsaken,

of dirt-studded & mold-streaked

treasures that no longer belong to anyonealive, overrunning

& overflowingly unkempt monuments to

the disappeared. Chronicle the heroes & mothers,

artisans who went to the end of the line,protectors & cowards.

The poet names these repositories as “galleries, gardens, herbaria.” But as the poem progresses, the heroes, mothers, and artisans appear, too, as their own museums: untidy, imperfect, a home or tribute for “the disappeared.” The line break between “no longer belong to anyone” and “alive, overrunning” masterfully conveys both impermanence and the fullness of experience.

So many of the poems in Anodyne speak to the liminality of the human condition, and, perhaps more importantly, of human consciousness, as we try to mediate between the present moment and everything that informs it. It strikes me that pain is also this way: Queen references chronic pain (both in interviews and in Anodyne’s Notes) that insists upon a kind of double consciousness—an acute feeling of the possibilities of “aliveness” in a particular moment. Even the absence of pain is notable: it is a loud silence. “Anodyne,” by definition, refers to “a painkiller,” something palliative. Queen’s poems wrestle with a multifaceted pain and ask difficult questions about how we take care. They hold space for a lineage of suffering, while at the same time longing for something else:

Something About the Way I Am Made Is Not Made

to make sense—I stretch my insides

across pages until my pain is upside down. Peonies &

tulips bloom red & pink from my back,

bent like washerwomen’s knees—

full-on shadow.

Here, the speaker’s own art-making juxtaposes her physical pain with something blooming and beautiful, though this image quickly turns to the bent posture and aching joints of the washerwomen. The “shadow” can be read as the shadow that pain casts over work, art, beauty, but can also be read as shadow lives, the existences that radiate from and through our own. The poem ends with a similar gesture:

For all my notes

& vices, I still long to stop the false

fight for my humanity, en masse, allowed to share

a history of anything but suffering

Anodyne is formally various. Through serial works, grid poems, erasures, and shifting points of view—from first-person monologues to a chorus-like second person plural—Queen creates layers and scenes that capture minute, miraculous gestures (“O pink lips first pulling on a Kool” and “a wasp on the stone poolside”) and the most expansive, and terrifying, of threats.

The final poem in the book, “I Slept When I Couldn’t Move,” draws from the author’s reading of Alice Notley’s In the Pines (2007) and the American folk/blues song “(Black Girl) In the Pines,” specifically the version sung by Lead Belly, first recorded in 1944. From the epigraph, in Lead Belly’s voice—“Black girl, black girl / Don’t lie to me / Tell me where / Did you sleep last night”—the poem takes off in response. The result is a stunning close to the collection—part memoriam, part confession:

I slept in a place that hadn’t been built yet & dreamt the sheer violence of

the futureI slept inside a song with a Blacker voice than mine which meant I slept good

I slept in the orange light of day silence

I never slept on the street

I slept in the knotted hair of my sister’s children in Detroit & washed & combed

it in the morning

I slept when I couldn’t move

I slept in a California desert, free of bodies & trees

I slept in senescent lake muck

I slept through earthquakes & El Niño & never stopped traveling

This final poem takes stillness and imbues it with so much movement. Here, sleep is an aperture that allows the reader to travel cross-country, over years, and through different degrees of risk, pain, exhaustion, beauty. “I slept so sure in a used place & so anonymous like womanhood & so hypervisible I slept in a kind of fire & became it.”

Reading Anodyne feels like learning a history and witnessing prophecy all at once. In this groundbreaking collection, Queen shows us that, though poetry is not a cure for pain, it can be a vessel that carries it. It can be a home for our grief, a reminder of what we might live for. “The world says not to expect the world,” Queen writes, “But do it anyway— be made, all / out of love—”

Published on June 21, 2021