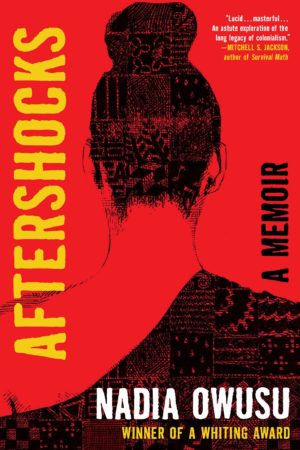

Aftershocks

by Nadia Owusu

reviewed by Jenni Sapio

Earthquakes aren’t just metaphors for Nadia Owusu, whose memoir spans the globe: Tanzania to Ethiopia, Rome to London to Arizona. In her first book, Owusu—an urban planner in New York City—illustrates the connection she made as a child between her own personal trauma and the shaky mantle of the earth. On the day Owusu’s absent mother makes an unexpected visit, tens of thousands of people died as a result of an earthquake in her mother’s ancestral land of Armenia. To suggest the psychic implications of this kind of terrestrial trauma, the author includes an anecdote recording Charles Darwin’s experience of a major earthquake: “An earthquake like this,” Darwin writes, “at once destroys the oldest associations; the world, the very emblem of all that is solid, moves beneath our feet like a crust over a fluid; one second of time conveys to the mind a strange idea of insecurity, which hours of reflection would never create.” Ever since the day of the Armenian earthquake, Owusu’s mental “seismometer” was sensitive to shock.

In her mother’s absence, Owusu’s Ghanaian father is the axis around which the eldest daughter’s world orbits. Her father works at the UN; this means that Owusu’s perspective was global but transient. She lived everywhere, but for a short while. Home for the author was wherever her father was. It wasn’t until fifteen years after his death, coupled with a miserably bad breakup and the shock of new information about her father’s potential AIDS diagnosis, that Owusu experiences a descent into madness, a week-long self-described “asylum” in a blue chair she’d found on the sidewalk near her apartment. In a world that calls mad women hysterical, and in which Black women are told to be “twice as good,” Nadia Owusu’s memoir is a courageous reflection on the fissures in a life and the intergenerational traumas that threaten Black women’s mental health.

In some of the most self-aware prose I’ve seen—alongside Kiese Laymon’s Heavy and Sarah Gerard’s Sunshine State—Owusu reexamines everything she’s come to understand in the twenty-eight years of life that led to the blue chair island. She faces what she survived (abandonment, domestic violence, sexual abuse, and terrorism) as well as what she ignored while she was surviving: civil wars, extreme poverty, child soldiers, global colorism, and the AIDS crisis. Like a seismologist surveying the geologic damage, Owusu details the “fault lines” where friction had been building for generations. She writes, “We know aftershocks are coming, but we don’t know when exactly. We don’t know how many. And we don’t know how long they will last.” Woven among powerful scenes in the chair are time-stamped vignettes where the friction intensified: her Ghanaian family’s involvement in the African slave trade, her white mother’s abandonment of her, her experience running from the World Trade Center subway stop on the morning of September 11th, her white boyfriend’s denial of Owusu’s experience of racism, her own “complicit freedoms” (in Claudia Rankine’s words), or the ways in which she benefitted from colorism and economic privilege.

The author’s demonization of her mother and idolization of her father were each “fanatical,” Owusu contends. By dismantling her idolatry of her father and complicating her own human experiences as both victim and perpetrator of suffering, Owusu is able to acknowledge the ways in which she too has been a “Bigot, prig, the voice in my head calls me. And, I must answer honestly. I must answer yes. I want to make it not so. I have work to do on myself. I need a new story.”

In her deft handling of history and memory, raging madness and crystal-clear insight, Owusu crafts a gorgeous work of art from the story of her life. After a lifetime of abandonment and wandering, Owusu is able to step into her own rights as creator, mothering herself home. She writes, “Mothering is a verb. It is done out of love and obligation. We approach it with kindness and grudge. I mother, you mothered, we will mother.” At the end of the book, we learn that Owusu has mothered herself out of the chair. Aftershocks, though, is the story of the eruption, not the reconstruction.

It’s fitting that in her day job, Owusu creates new worlds by planning cities. She imagines new ways to live on top of the old fissures and faults. By telling long histories and diving deep into an intersectional understanding of her life, Nadia Owusu charts a way forward for herself and for all of us, as we look for home within our own stories.

Published on July 6, 2021