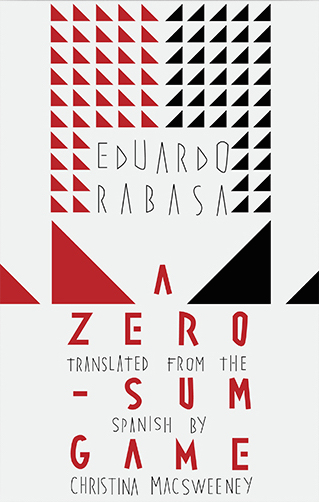

A Zero-Sum Game

by Eduardo Rabasa, translated by Christina MacSweeney

reviewed by Gabriel García Ochoa

In his essay “The Other Voice,” Mexican Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz brilliantly deconstructs the French motto, liberté, égalité, fraternité. According to Paz, the most important word in that powerful triumvirate is fraternité, friendship, our mutual feeling of respect and support for each other. Without fraternité, Paz argues, the entire system collapses, festering into a dog-eat-dog world. Liberty without fraternity results in a loss of equality; this is unbridled capitalism. Equality without fraternity leads to a loss of liberty; this is unbridled socialism. Fraternity is the axis that balances the spinning forces of liberty and equality, stopping one from suffocating the other.

In the world of Eduardo Rabasa’s first novel, A Zero-Sum Game, fraternity has all but disappeared. The story takes place in a run-down housing complex, Villa Miserias. Things start to change in Villa Miserias with the arrival of Selon Perdumes. He teaches the people of Villa Miserias his philosophy of “Quietism in Motion.” Quietism, because those in the lower echelons of society should not question the dictums of the governing class; in motion, because social progress is good and necessary when it is properly administered by said ruling class. Perdumes offers the people of Villa Miserias everything they ever dreamed of; of course, no one can afford their dreams, and this is where Perdumes’s mellifluous cajoling, high-interest loans, and veiled threats to those who refuse to adapt to the new order come into play.

Soon, behind the semblance of a “democratic” system that allows the people of Villa Miserias to elect the president of the residents’ association, Perdumes amasses power and becomes the puppeteer behind every action, every business, and every decision in Villa Miserias. He even controls “the media,” the squalid local newspaper aptly named The Daily Miserias (The Daily Miseries). But one day, young Max Michels decides to challenge the system and run for president of the residents’ association without Perdumes’s permission. What follows is a page-turning campaign that lasts eleven days.

It seems everything happens in Villa Miserias: drug trade, corruption, art, tyranny, love, manipulation of the media, the rise and separation of distinct social classes. Rabasa’s microcosm discusses many topics with ease and good humour, but the book focuses most of its energy on politics. Villa Miserias encapsulates a financial system that pushes its residents to live beyond their means. It is a perfect neoliberal market, where credit creates the illusion of freedom as it breeds a social stratum forever bound by debt. As Max Michels explains to his potential voters, poverty is necessary in Villa Miserias; it is a crucial part of the game.

Let’s get it straight, once and for all: poverty is not an evil to be eradicated by development. On the contrary, it is a vital component of the present social fabric. It is the fuel that keeps society productive. While there is need, there will be no limit to how low we set the standard of what is acceptable.

The omniscient, omnipresent political system of Villa Miserias is at times Orwellian; at times it reminds me of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, as the residents of Villa Miserias are manipulated into trading their freedom and rights for cheap entertainment and the appearance of a just, democratic order.

After the 2016 election in America, a critique like this on the potential pitfalls of democracy rings with an eerily relevant timbre. The narrator never mentions the location of Villa Miserias, neither the country nor the city, but this type of sprawling housing complex is common in Latin America. The obscene abuses of power and manipulation of the electorate that takes place in Villa Miserias are also characteristic of many Latin American countries, where an adequate system of checks and balances does not work with the efficiency that it does in other parts of the world. In September 1990, during a live debate on Mexican television, the titan of Latin American literature Mario Vargas Llosa famously declared that Mexico was the most perfect dictatorship. Not the dictatorship of a leader, not a dictatorship along the lines of Fidel Castro’s Cuba, but the dictatorship of a party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party), which held uninterrupted power for seventy-one years until 2000, moving from one president to the next without true social change, but under the guise of democracy. An approach remarkably similar to Perdumes’s “Quietism in Motion.”

Other than Perdumes’s philosophy, another element of the text that places the story unofficially in Mexico City is its use of localisms. This is something that unfortunately gets lost in Christina MacSweeney’s beautiful translation (through no fault of hers) simply because English can never be Mexican in the way Spanish can. MacSweeney’s recent translations of another up-and-coming Mexican author, Valeria Luiselli (The Story of My Teeth, Sidewalks) have received much acclaim in recent years. Her work with Rabasa’s novel surpasses the standard she has set, making A Zero-Sum Game a pleasure to read.

Published on June 7, 2017