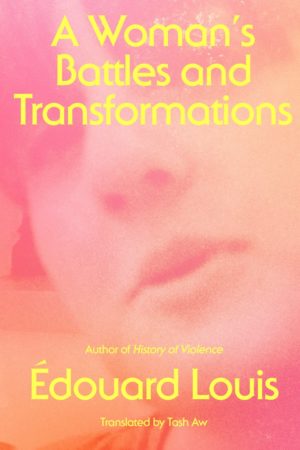

A Woman’s Battles and Transformations

by Édouard Louis, translated by Tash Aw

reviewed by Rhoda Feng

Born in 1992 in a working-class village in the north of France, Édouard Louis made his debut with The End of Eddy, a book about the homophobic assaults he suffered at the hands of classmates, his rejection of the cult of masculinity, his strained relationship with his taciturn father, and his burgeoning interest in theater. It was a form of emancipation—the title signaled his decision to change his name from the one his parents gave him—that also hinted at something darker. “I wanted to kill him,” Louis told an interviewer, “he wasn’t me, he was the name of a childhood I hated.”

The End of Eddy became a surprise bestseller, being followed, in quick succession, by History of Violence, a gripping account of Louis’s rape and his subsequent ambivalence about seeking justice through officially sanctioned channels, and Who Killed My Father, a fragmentary tract that combines blistering political critique with an abbreviated history of his father’s life. Readers might not know, from reading that work, that Louis’s father is still very much alive: the book is cannily structured as a philosophical inquest. Louis is unafraid to name names responsible for his father’s premature death: Nicolas Sarkozy, François Hollande, Jacques Chirac, and Emmanuel Macron all share the blame for forcing his father to return to work when he was physically ailing, with a factory-mangled back and distended belly “torn apart by its own weight.” Yet the work was not without shades of self-incrimination, with Louis-the-coroner covertly attempting to get a bead on Louis-the-would-be-patricide.

The latent desire of Who Killed My Father becomes an eruption of guilt in A Woman’s Battles and Transformations, the latest of Louis’s books to be translated into English. Halfway through this new work comes an admission that distinguishes it from its antecedents:

Most people who speak about their trajectory passing from one social class to another recount the violence they experienced in the process—because of their inability to adapt, their ignorance of the codes of the world into which they were entering. I remember mostly the violence I inflicted.

The violence he has in mind is primarily against his mother, a character only glancingly alluded to in his earlier works. When she marries Louis’s father, she effectively signs away much of her autonomy. On her thwarted wish to get an abortion, for instance, Louis writes: “He decided, she ceded.”

Crisply translated into English by Tash Aw, the slim work forms a triptych with The End of Eddy and Who Killed My Father. A gloomy atmosphere, continuous with the book’s prequels, prevails for the first part of the book. Once again, we encounter Louis’ father, a figure who creates a pool of misery around him, submerging his sons and wife in his bilious moods. The prose is restrained, only occasionally interrupted by lines of stabbing lyricism. “Poverty always adheres to an operating manual that no one has to spell out,” Louis writes. In The End of Eddy, the young Édouard’s trips to grocery stores are studies in humiliation: more than once he must ask for food on credit from a store clerk, who ostentatiously reminds him that her forbearance has its limits. Shame about his family’s poverty is another major theme of A Woman’s Battles and Transformations. “No one explained it to me, but I knew that I couldn’t tell anyone in the village about these trips to the food bank,” Louis reflects. There are brief snatches of happiness with just his mother—a visit to a traveling circus, a race in the mountains—but the arrival of more children brings “catastrophe.” When Édouard enrolls in high school, then a university in Amiens, the rift between him and his mother widens. On one occasion, she dismisses his stomach pains as a bourgeois affectation and tries to dissuade him from seeing a doctor. Against her wishes, Édouard sees a doctor, who tells him his appendix has been infected; waiting much longer would have been fatal.

Just when Louis deems his middle-aged mother’s life “already fixed forever,” she undergoes a metamorphosis. A year after the medical scare, she decides to leave his father. The news does not exactly come as a surprise to Louis; when she calls to tell him, “I understood immediately what she was talking about.” The two share an almost conspiratorial glee, as if reconstructing “an escape or a burglary that the two of us had worked out together, patiently, secretly, for months and years.” Gradually, the great glacier of mutual estrangement begins to thaw. She moves into a public housing unit with Édouard’s younger brother and sister, finds work as a home health aide, and even gets the chance to meet the actress Catherine Deneuve after Louis lets slip that his mother is a fan. Transformations beget more transformations. Louis’s mother later moves to Paris, changes her last name, takes a lover, wears makeup and new clothes, and becomes politicized enough to start using expressions like “woman’s pride.”

In its treatment of filial themes and habitual recourse to the second person, Louis’ book shares overt similarities with another semi-autobiographical work written by a gay man to his mother: Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Barthes is also a touchstone for both. With Camera Lucida, Barthes sought to magically conjure up the body of his mother: it is Barthes’s true Lover’s Discourse. Louis attempts something similar, maybe even more ambitious, with A Woman’s Battles and Transformations: he seeks to both retroactively restore agency to his mother, offering his book as a kind of psychic bomb shelter “in which she might take refuge.” The book ends with a photograph of Louis’s mother, head tilted to the side, with a youthful haircut and inquisitive expression on her face. We not only see the resemblance to her son, with whom she appears in other photos, but we can almost hear the question being formed on her slightly parted lips: “What next?”

Published on August 16, 2022