100 Poems

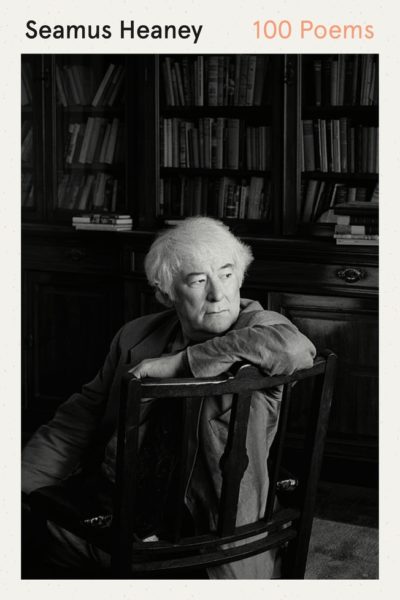

by Seamus Heaney

reviewed by Kevin T. O'Connor

A poet of original vision and technical mastery, literary accomplishment and popular reach, Seamus Heaney has made an indelible impression on the culture of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. 100 Poems will likely become the standard introduction to his work, the one assigned in English classes or given as a gift. Since Heaney’s reputation as a poet is rivaled only by the legend of his personal generosity, it seems fitting that these selections should be made by his immediate family (his wife, Marie, and children Catherine, Michael, and Christopher), whose loving and intelligent tribute highlights the healthy continuum between Heaney’s life and art. Consciously excluding his major work in translation (Sweeney Astray, Beowulf, and others), 100 Poems includes not just a selection of Heaney’s most celebrated poems of a career spanning nearly half a century, but also those holding “special resonance for us as individuals,” as Catherine Heaney explains in “Family Note.” But this more intimate familial appreciation expands seamlessly to include the Irish nation and a global community of poetry readers.

Dedicated readers of Heaney will look to his Opened Ground: Selected Poems 1966–1996, or the duo of Selected Poems 1966–1987 and New Selected Poems 1988–2013, and for them 100 Poems will inevitably provoke affectionate outrage about favorites left out (“What? No ‘Bog Queen’?! No ‘From the Frontiers of Writing’?!”). But given the quality, variety, and amplitude of Heaney’s oeuvre, these “in-house” selections prove to be both representative and balanced. On the few occasions where romantic or familial touchstones (e.g., the early courting poem “Twice Shy”) have displaced more ambitious poems, readers can afford to be indulgent amid so many riches, where Heaney’s deep currents of thought and feeling are channeled into words.

The volume begins with nine poems from Heaney’s debut collection, The Death of a Naturalist (1966)—the first is his signature piece, “Digging”:

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

Rarely does a poet appear having already found his distinctive voice—a voice tapped into the music of nature. After these early foundational poems, often set in the nurturing ground of his family’s farm at Mossbawn, selections quickly begin to reflect the Troubles, the sectarian and nationalist conflict that broke out in Heaney’s native Northern Ireland around 1968 and raged for the next three decades. A number of these are moving elegies like “Casualty,” written for a fisherman friend killed in a pub bombing, and “The Strand at Lough Beg,” for his neighbor-cousin Colum McCartney, victimized at a country roadblock. In “Exposure,” Heaney recounts his own self-conscious exile in the Republic of Ireland, identifying with the natural landscape of County Wicklow as with the Catholic minority:

[ … ] a wood-kerne

Escaped from the massacre,

Taking protective colouring

From bole and bark [ … ]

Finding metaphors in recent archaeological discoveries, Heaney makes his most original art about the Troubles in his “bog body” poems: “The Tollund Man,” “The Grauballe Man,” and “Punishment” allow Heaney to explore the etiology of the conflict with atavistic images of tribal rites dating back as far as the Iron Age. Like Yeats a half-century before, trying to illuminate historical trauma without romanticizing its “terrible beauty,” Heaney brings a moral tension to his reverent description of the Tollund Man, hung “in the scales / with beauty and atrocity.”

Drawing from a deep well of Irish myth and legend, 100 Poems demonstrates why Heaney was beloved as the country’s unofficial poet laureate. In this light, his mid-career sequence Station Island (1984) seems emblematic. Its premise—the agnostic poet performing a ritual pilgrimage at the holy site of Lough Derg—sets up charged colloquies with personally and culturally significant ghosts, where Heaney can speak with Dantean scope while staying in touch with his own terra firma. Ventriloquizing the voice of James Joyce in the poem’s peroration, Heaney breaks through the quarrels with himself to hit an aspirationally sublime note:

‘ [ … ] That subject people’s stuff is a cod’s game,

infantile, like this peasant pilgrimage.You lose more of yourself than you redeem

doing the decent thing. Keep at a tangent.

When they make the circle wide, it’s time to swimout on your own and fill the element

with signatures on your own frequency,

echo-soundings, searches, probes, allurements,elver-gleams in the dark of the whole sea.’

Though the Troubles may have created Heaney as a Nobel sage, 100 Poems reflects the broader scope of a poet who could lift the quotidian dramas of ordinary people to a transcendent plane of regard. “Clearances,” his series of intimate elegies for his mother, is tender and heartbreaking. Selections from The Haw Lantern (1987) show off Heaney’s talent for personalizing allegory, with the speaker of “From the Republic of Conscience” becoming a “dual citizen” of not only his birth country but also of “that frugal republic” of moral awareness, never to be relieved of his newfound duty “to speak on their behalf.” In the mystical glintings of “At The Wellhead” and “St Kevin and the Blackbird,” Heaney makes room—as he said he hoped to do in his Nobel lecture—“for the marvelous as well as for the murderous.”

The selections representing the last phase of Heaney’s career often seem to enact a contest between memory as revitalization and death as a foreboding release, as in the title poem from his last—and one of his best—collections, Human Chain (2010):

That quick unburdening, backbreak’s truest payback,

A letting go which will not come again.

Or it will, once. And for all.

Heaney’s particular faith in the human is revealed in “Miracle,” a tribute to those who physically carried him to the ambulance after his stroke:

Until he’s strapped on tight, made tiltable

And raised to the tilted roof, then lowered for healing.

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

Unflinching in its images of suffering, 100 Poems also offers consoling epiphanies—of other people, nature, art—which, as in “Postscript,” can surprise, “And catch the heart off guard and blow it open.”

Published on October 8, 2019