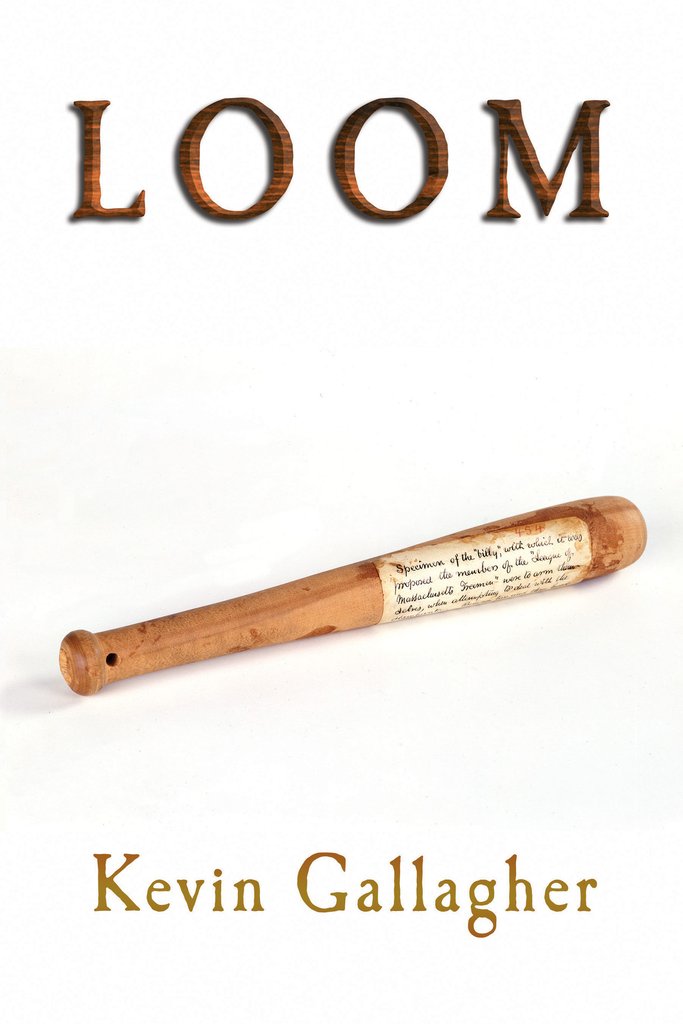

Loom

by Kevin Gallagher

reviewed by Kevin Bowen

“It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.”

These lines from the end of Williams Carlos Williams’s Asphodel, That Greeny Flower have been so often cited that I fear their history being lost. With Williams, contexts and origins are essential, and it’s important to remember that the poem made its appearance against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement, the nuclear arms race, and the Red Scare. At a moment when schools began conducting air raid drills and propaganda was flourishing, as citizens turned more and more against each other and people were, in fact, dying quite “miserably,” the truth that could be found in poetry needed—in Williams’s mind—to be reasserted.

Writing poetry that might speak to such times is and was a challenge. Levertov, Rukeyser, Hayden, Olson, Walcott, Dove, and others have taken up the challenge after Williams. Recently, collections such as Robin Coste Lewis’s The Voyage of the Sable Venus, Claudia Rankine’s America, and Martha Collins’s White Paper have extended the tradition, taking on the essential American subjects of slavery, race, gender, inequality, and justice. With the publication of Loom, Kevin Gallagher’s name must be added to that list.

Gallagher has been on this trajectory for some time. I first met the author when he was a recent graduate of Northeastern University; he and a few friends had just begun publishing that remarkable 1990s broadsheet-sized journal, Compost. The event was a celebration of Carolyn Forché’s landmark anthology of poems of witness, Against Forgetting, featuring Forché, Charles Simic, and Bruce Weigl, billed also a fundraiser for the Huế Central Hospital in Vietnam. The group had come hoping to interview Forché, and, in their enthusiasm, ended by volunteering to publish the first translations of Vietnamese poetry in the United States since the war. I’ve followed Gallagher’s work ever since, knowing he is a poet always willing to take up difficult conversations.

Loom joins this poetic conversation from the critical vantage point of economics, as Gallagher is also a professor of global policy at Boston University. He carefully details the workings of the system, which, while generating wealth for a handful of New England families, meant pain, misery, and death for hundreds of thousands of others. It was a system that made for strange bedfellows, as Gallagher notes early on in “Tariff Act,” a poem in the voice of Thomas Jefferson in 1816; he describes a system that resonates still today with current talk of walls, protective tariffs, and national security:

I am not a Hamilton man

in a ragebut just this time

the plantation and loomneed to be behind

the same wall.

True to its title, the format of the book intersperses poems, most plainspoken, most in sonnet form, with reproductions of prints, handbills, and newspaper pages; the effect is that the collection reads alternately as an almanac, primer, gazette, even a street pamphlet as it offers the reader a richly interwoven texture of public and private testimonies.

Chronologically speaking, the poems move from Francis Cabot Lodge’s theft of plans for mechanized looms from English factories through the collaborations of Northern mill owners with Southern planters, on through the birth of labor agitation, the Abolitionist movement, the Anti-Man-Hunting League, the founding of Lawrence, Kansas, and the slaughter of African-American volunteers of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War.

Individual poems give voice to personal histories as, in unison, the poems circle and sing the problematic history of Boston and the shadowy origins of its wealth. (Perhaps not a coincidence, Gallagher’s newest editorial undertaking, spoKe, centers on writing about or having its origins in the city).

The poem “Boston Anti-Man-Hunting League” is written in the voice of the league’s members, Henry Bowditch, in 1854. It takes its lead from a directive on how members should circle, approach, and chase off slave hunters while freeing the captured slaves. A diagram of the plan accompanies the poem.

A committee of six: prudent, young, true,

and stalwart comrades—with one elderspeaker—are first to try your hands at reason.

If the Southern blood arises the speakersignals and we begin ‘the snaking out.’

Keep the slave hunter (SH) in center.

While the poems may follow sequentially, there is a lyric quality in the ways they speak to each other and the manner in which refrains and end lines reappear. Taken together, the poems constitute a chorus sung by voices of wealthy Brahmins, mill workers and owners, escaped slaves, ship captains, labor agitators, and abolitionists.

Fittingly, Gallagher ends the collection with a poem in the voice of a dying soldier of the 54th regiment:

Too many rocks for our wooden wheels.

Too many dying men and horses

to move our Napoleons back.We saw Bigelow get shot twice

but the bugler took him to the rear.

We kept on trying to fight.I got stabbed in the ankle.

I felt the shell go in my side.

My eyes were open when I died.(“The Last Full Measure of Devotion”)

Like much of Gallagher’s previous involvements—in particular Compost—the collection has the feel of an object, something handcrafted and unique. Those familiar with Gallagher’s work will be happy to discover this newest effort. Readers just coming to his work will find something new and valuable to add to “the tool kit for living” that Williams suggested poetry should be.

Published on July 11, 2017