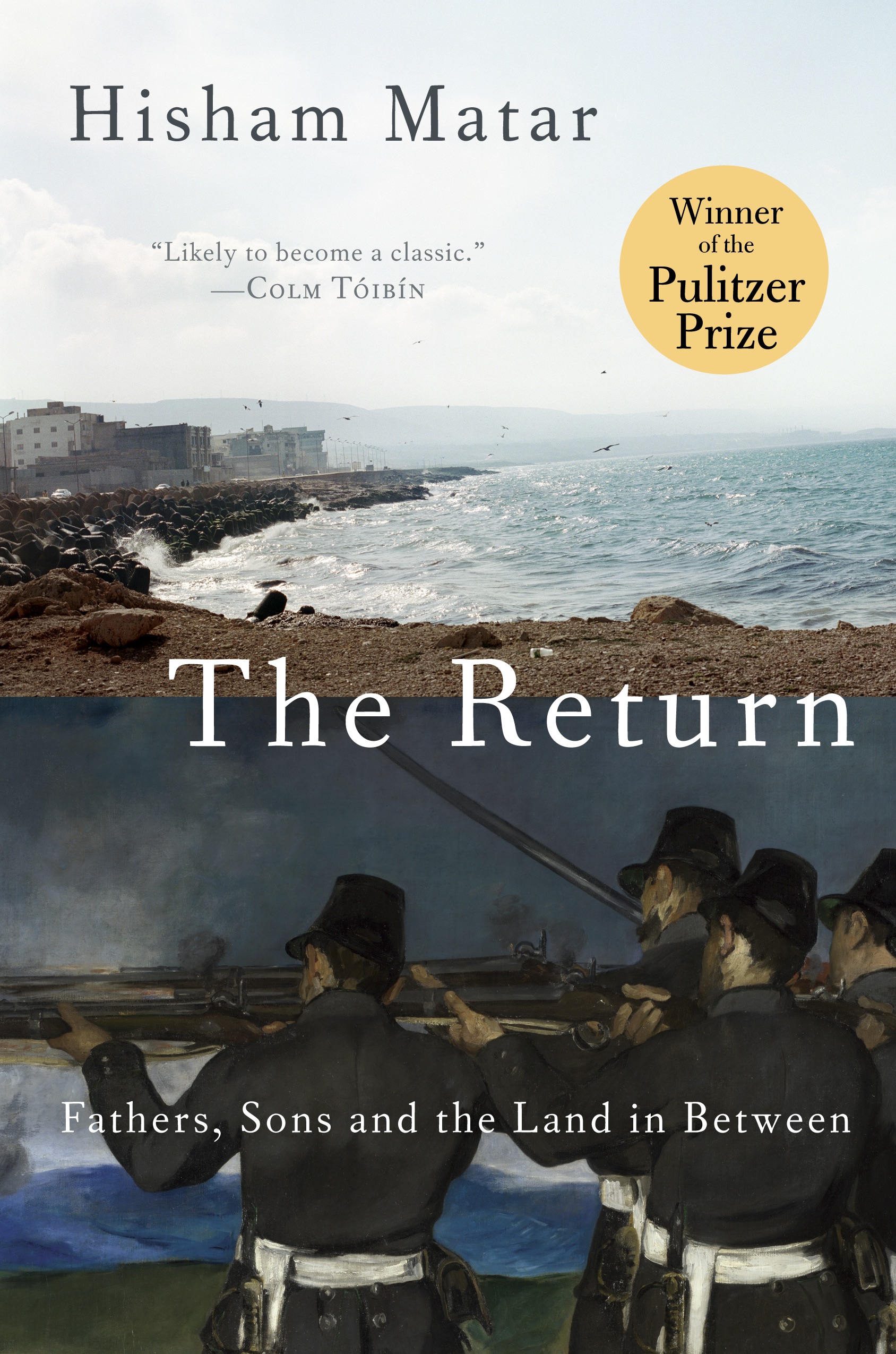

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between

by Hisham Matar

reviewed by Carmen Bugan

The writer Hisham Matar has spent most of his adult life not knowing whether his dissident father is dead or alive. At one anniversary marking his disappearance, the family gathered in the “surrogate” city of Nairobi, whose earth he describes as “an inkwell,” and “told and retold the story of how it had happened.” Just days later, everyone flew home to a different country.

Matar has won this year’s Pulitzer Prize in autobiography/biography for his memoir The Return, described by the committee as “a first-person elegy for home and father that examines with controlled emotion the past and present of an embattled region.” Born in New York City to Libyan parents, Matar divided his childhood between Tripoli and Cairo, was educated in England, and has enjoyed success from the outset of his literary career. His first novel, In the Country of Men, won six international literary awards and has been translated into twenty-eight languages. Anatomy of a Disappearance, his second novel, was named one of the best books of the year by the Chicago Tribune and The Guardian. Yet it is Hisham Matar’s memoir that puts him among the strongest contemporary writers. His book, both a chronicle of private family pain and an historical account of life under Gaddafi, creates a space for reflection on freedom and humanity. As a piece of literature it reminds one of Milosz’s conviction about poetry: it is, the Polish Nobel Laureate said, “on the side of being and against nothingness.”

Twenty-two years after Jaballa Matar, one of Gaddafi’s most vocal opponents, vanished into the Abu Salim prison, his son Hisham Matar took his wife and mother to Libya to find him. His voice reverberates with pride for his father’s courage, the years of fruitless search for information about his disappearance, and exile. We follow Matar to a changed and changing Benghazi and see him visiting a deeply wounded but resilient extended family who gather together over fragrant meals, memories, poetry, and innumerable cups of tea in houses, apartments, and in the otherworldly desert. We meet Matar’s dissident grandfather, who opens his shirt to show the place where a bullet has entered his body, and Matar’s mother, who houses and feeds women whose sons and husbands had joined the resistance and were incarcerated in the same prison as Jaballa Matar. We learn the story of a woman who spent years delivering monthly packages of food and toiletries to her son, unaware that he had been murdered in the prison where she had been accepting the guards’ varied excuses for not granting her a visit.

Libya is seen through the eyes of its estranged son who longs for the sea, who meditates on the architecture trampled by invaders, who has known other countries, who is buffeted by his native Arabic and the English language in which he now writes. Yet the quest of the book remains Jaballa Matar: the father, the inspirational leader, the writer, the poet, the prisoner, the disappeared. Jaballa becomes larger than life, the symbol of truth to power and at the same time the painfully absent father. It is in this dual role as father-hero that the story of political brutality is told. To Matar, the absence of his father “has never seemed empty or passive but rather a busy place, vocal and insistent.” He carves into language to shape this absence, to express the loss of his father, and in turn records a loss within himself, saying: “I do not have a grammar for him.” “Grief,” he explains, is “an active and vibrant enterprise. It is hard honest work. It can break your back.” For him, this grief enters words themselves.

What gives his book a special place in the literature of witness is the full employment of lyric language in order to intimate the ravages of history, the cruelty and indifference of the powerful, and to find solace in art, nature, and family. Gaddafi and his son are portrayed through the monstrosity of their actions. The language goes beyond Matar’s personal story to that place of conscience where his torment becomes an occasion for self-reflection. To those families who stood up for freedom and have paid for it with prison and exile, Matar’s book is the place where they can recognize a similar loss. His words traverse territories of languages and cultures and carve into the consciousness of literature a Jaballa Matar who will not disappear. Of the Libyan political prisoners he encounters, Matar says something achingly familiar to those who fight oppression everywhere: “They wanted to bring me into the darkness, to expose the suffering and, in doing so, discreetly and indirectly emphasize the momentous achievement of having survived it. Is there an achievement greater than surviving suffering? Of coming through mostly intact?”

Published on June 15, 2017