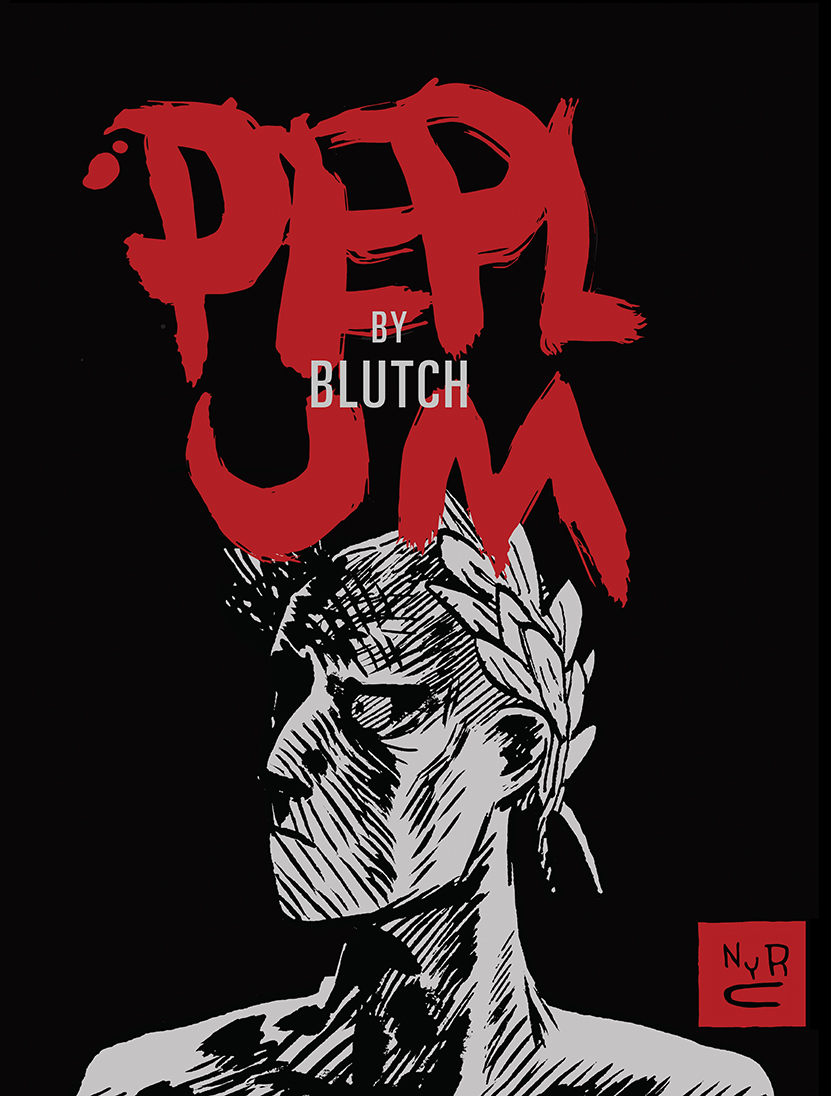

Peplum

by Blutch, translated by Edward Gauvin

reviewed by Paul Hanna

Films making up what was once known as the “peplum” or “sword-and-sandal” genre are quite a niche area of film interest. The genre often deals with muscle-bound men performing heroic or otherwise spectacular acts with badly dubbed dialogue. Films in the peplum genre were epic in scope, but never quite measured up to their Hollywood counterparts—Ben-Hur, Spartacus, even Jason and the Argonauts. The bulk of them made use of typical swashbuckler adventure tropes: heroes, villains, and damsels in distress.

Blutch’s Peplum flips almost all of the stylish Hollywood exuberance of the genre—his protagonist is a desperate, obsessed, and skinny vagabond mostly trying to survive—but embraces a lot of the literary qualities shared by these films and the plays and epics of ancient Greece and Rome. But despite its title, calling this a genre work is a gross mistake. The chapters are almost like fragments, perhaps evoking the mythical bizarreness and intensity of some classic, epic Odyssean trial, but more grounded in the general realm of human vulnerability, terror, absurdity, and humiliation rather than epic-scale heroics. Blutch’s Peplum itself is a fevered, unorthodox non-quest rather than some three-act adventure.

Edward Gauvin’s introduction to this first English edition describes Peplum‘s impetus as a comics adaptation of The Satyricon by Petronius, but becoming something very different during the creative process (for instance, Blutch shifted the setting to ancient Rome from ancient Greece—presumably to include the fall of Julius Caesar). Gauvin also acknowledges Peplum‘s cinematic influences—and Blutch’s complicated relationship with those influences as a cartoonist. He notes previous artists such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, who adapted classic works into films like Medea, The Decameron, Arabian Knights, and The Canterbury Tales, as well as Federico Fellini and Pasolini’s adaptation of Petronius’s work, Fellini Satyricon.

By design, the book’s chapters are light on plot. The main through line of the book is the protagonist’s frantic, panicked quest to recover the (literal) object of his obsession, a would-be goddess who is encased in ice, both a false idol and a false ideal. The story becomes darker and darker, moving from more classically peplum (the film genre) trappings towards sequences that are more grounded in surreal trappings of archetypical fable and myth, peppered with ironic and darkly amusing moments throughout. Each chapter incorporates more surreality and less reality.

Where Peplum excels superbly is its understated use of geometry, both within a single panel’s composition and the overall arrangement of panels on the finished page. This is arguably Pasolini and Fellini’s biggest influence on Peplum, aside from the story material. Blutch traditionally works using austere linework and black-and-white contrasts to their most vivid effect. Peplum‘s most powerful moments are when this aesthetic is combined with Fellini and Pasolini’s sense of composition, using objects within the frame to highlight figures and other objects. But where Fellini evoked an objective sense of fantasy with this technique, and Pasolini used facial close-ups to create subjectivity or draw out emotion, Blutch’s application of this technique in the comics medium is somewhere off this axis completely, often serving a larger point of highlighting some aspect of human cruelty or irony.

Fellini and Pasolini were praised for stripping down elements of plot and story to lay bare an individual’s humanity, eschewing conventional morals. But when Blutch does this, the result is often darker; he lays bare a pre-civilized emotional baseness (an id, if you want to get Freudian about it) and animalistic desire. That path, while it does not take anyone in Peplum towards redemption, per se, does eventually come to a reckoning and an acceptance of things as they are. In the bizarre, nightmarish landscape that is Peplum, this attainment of knowledge leads to a warped conclusion.

Published on October 4, 2017