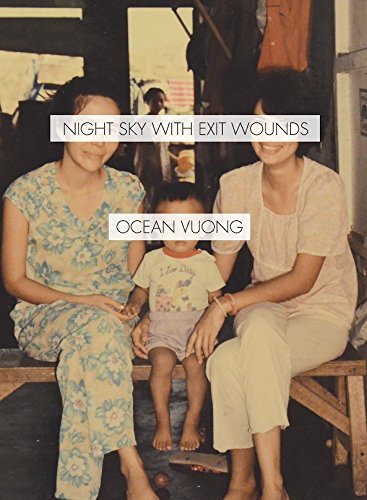

Night Sky with Exit Wounds

by Ocean Vuong

reviewed by Peter LaBerge

Religious Freedom Restoration bills; North Carolina’s controversial bathroom bill; the LA Pride bombing attempt; the horrific Pulse shooting. It seems no matter how we approach it, 2016 has not been kind to LGBTQ+ Americans, yet it is in this context of darkness that Ocean Vuong’s breathtaking poetry collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds, shines most brightly.

The 2016 Whiting Award recipient’s highly anticipated debut collection serves as both a respite for a grief-stricken queer America and a haunting, evocative glimpse into life as a queer immigrant of color. These are poems that, seemingly out of necessity, harvest their speaker’s experiences for the beauty, light, and life they contain. They leave much in their wake—particularly for those ill-acquainted with queer identity and its nuances—in a time when fear, intolerance, and an unwillingness to listen influence both our society and the politics within it.

The collection’s first section begins with Vuong’s poem “Telemachus,” an intimate portrait of the speaker’s relationship with his father. Here, we find a father with a “face / not mine,” a father who “is so still … he could be anyone’s father, found / the way a green bottle might appear // at a boy’s feet.” By the end of the poem, we recognize the speaker’s distance from both the individual and the notion of traditional masculinity that his father represents, a distance that becomes increasingly well-defined as the collection develops. “Telemachus” sets the stage for a harrowing exploration of queerness and family. Vuong’s statement that “your father is only your father / until one of you forgets,” from “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong,” recalls the speaker’s opening question, “Do you know who I am, / Ba?” and “the answer [that] never comes.” In “Prayer for the Newly Damned,” Vuong asks directly, “Dearest Father, what becomes of the boy / no longer a boy?” The father’s inability or refusal to resolve such uncertainty is a silence that speaks for itself.

Throughout the collection, Vuong displays a relationship with his mother that is as close as that with his father is distant. As the collection builds, tenderness and subversion characterize our developing understanding of Vuong’s personal and sexual selves. In “Into the Breach,” he writes, “I just don’t know / how to love a man / gently. Tenderness / a thing to be beaten / into.” In “Always & Forever,” Vuong’s speaker applies childhood memory to illustrate the internalization of this tenderness and its accompanying subversion when “[his father’s] thumb, / still damp from the shudder between mother’s // thighs, kept circling the mole above my brow.” Finally, “Because It’s Summer” brings the association of sexual subversion with feminine influence into actualized focus:

you kissed your mother

on the cheek before coming

this far because the fly’s dark slit is enough

to speak through the zipper a thin scream

where you plant your mouth

In fact, Vuong credits his entire existence with his maternal grandmother’s subversion: “An American soldier fucked a Vietnamese farmgirl. Thus my mother exists. / Thus I exist.”

In Night Sky with Exit Wounds, Vuong accomplishes with sophistication and grace what many poets only strive to accomplish: he invites us to experience a world where hardship and isolation are expectations. Just as queerness becomes the vessel through which Vuong approaches his exploration of family, his most intimate moments become vessels through which the nuances of queerness may be understood. By placing struggle and tension at the center of the collection, Vuong allows us to engage with queer identity on a deeper, more evocative level. Before long, we are confronted with poems that depict queer men wondering “if dancing could stop the heart / of [their] murderer”; queer men saying “forgive me because that’s what you say / when a stranger … offers you another hour to live”; queer men who “step, hand in hand, / into the bomb crater.” There is immense pain and fear in the minds of queer men around the country, and the poems of Night Sky with Exit Wounds incorporate this pain and these fears as reality. Perhaps Vuong himself best describes the power of his voice in the poem “Threshold” when he writes, it “filled me to the core / like a skeleton.” This voice, Vuong’s necessary, shimmering voice, fills us to the core.

Published on December 13, 2016