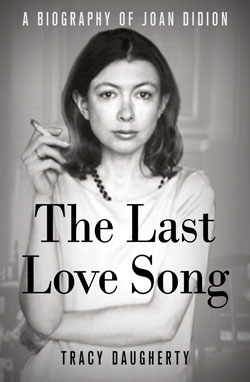

The Last Love Song: A Biography of Joan Didion

by Tracy Daugherty

reviewed by Maia Silber

On an August afternoon in 1973, Joan Didion brought her seven-year-old daughter, Quintana, to the Chicago Institute of Art. Quintana stood in front of O’Keeffe’s “Sky Above Clouds” and said, “I need to talk to her.” The girl never met the painter, but eight years later, Didion considered Quintana’s words in an essay on art as self-representation. A painter’s work makes us want to meet her, Didion concluded, because “style is character.”

Martin Amis noted in the London Review of Books that we can find evidence to the contrary in any literary biography, a remark which appears in Tracy Daugherty’s recently published biography of Joan Didion. Daugherty’s work, the first comprehensive account of the writer’s life, is also a 600-page meditation on the statement “style is character.” Daugherty read Didion and needed to talk to her. Like Quintana, Daugherty never met his idol; Didion did not cooperate on the project.

Daugherty’s only extensive interview is with Noel Parmental, an ex-boyfriend who once sued Didion for libel. Mostly, Daugherty engages in extensive dialogue with Didion’s autobiographical works and archived manuscripts. In doing so, he encounters a particularly tangled style and character. Since she began her career as a staff writer for Vogue, Didion’s approach has been extraordinarily personal. In her first column for Life, she pondered divorce. In her seminal collection of essays, The White Album, she transcribed her psychological profile. Her memoirs, The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights, detail the deaths of her husband and daughter, respectively. Yet these works communicate the personal in a fragmentary, elliptical, and repetitious prose as distinctive and obscuring as her famous sunglasses. Any consideration of Didion must take into account this careful exploration of her self and her equally careful construction of that self, the persona she creates, and the mythos that has formed—with or without her control—around her.

These concerns do not escape Daugherty. He promises, in the biography’s preface, to approach Didion’s writing with attention to the distinctions between persona and personality. Yet in seeking the self in the construction of sentences—Daugherty’s first project is to reconstruct Didion’s prose—he often imitates her in lieu of analyzing her. Themes emerge around repeated Didionesque phrases, I don’t know what happened to this country; Just change the script. As Daugherty narrates Didion’s life, he pulls details from her published works: the yellow curtains hanging from her New York window, Quintana’s fuzzy pink slippers, Dunne asking for a second drink before dropping dead of a heart attack. The technique blends Didion’s words into the events of her life. Used to best effect, it demystifies her processes, unearthing the trail from observation to draft.

Used less delicately, this technique can make Daugherty’s prose read as a near-parody of Didion’s. “On those blue, blue nights, slouching toward a center that would not hold … this writer was always true,” Daugherty combines nearly every iconic Didion line in the biography’s closing chapter. “If we pause and bother to listen, we remain dreamers of Didion’s dream.” Details intimate in memoir can seem silly in biography. Daugherty describes a college-aged Didion walking to class, “fingering bags of peanuts in her pockets.”

In Didionesque fashion, too, Daugherty draws his major themes from a dark and romantic mythic past. He traces both Didion’s spare prose and political conservatism to her “wagon-train morality,” the pioneer legends of her Western upbringing. Though Didion, writing for The American Scholar, first identified “wagon-train morality” in a nurse’s decision to retrieve a dead body from Death Valley, Daugherty interprets the phrase to mean leaving the body behind. In Didion’s accounts of the acid-tripping girl in “High Kindergarten,” the child left alone on a California freeway, and the abortion in Play It As It Lays, Daugherty sees the weak one left on the trail. It’s an apt if obvious metaphor for Didion’s treatment of loss and abandonment and for the social and political changes of the twentieth century that she both exemplified and recorded. Daugherty frames that era, with its promise of forward motion and brutality of sacrifice, as a crasser pioneering age. “The casualties from that period lay all along the trail,” Daugherty writes of the sixties coming to an end. “Morrison, Joplin, Hendrix.”

When it comes to Didion’s character, though, less fits into metaphor and myth. Can we liken writing The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights to burying the baby, or refusing to continue along the trail? “What governs [a life] is not pattern but drift,” Cynthia Ozick wrote in an essay on Edith Wharton. Even as Didion wrote about crossings, she drifted, from California to New York to Hawaii to California and back to New York again. Daugherty charts the trail from style to character, but we’re left wondering what went off the trail.

Didion concludes her essay on O’Keeffe by recalling the inspiration for the artist’s “Evening Star” series. O’Keeffe observed the star on evening walks with her sister, while her sister practiced her aim by throwing bottles into the air and shooting them. “In a way one’s interest is compelled as much by the sister Claudia with the gun as by the painter Georgia with the star, but only the painter left us this shining record,” Didion concludes. In the end, only Didion the writer left us her shining record. Didion the woman drifted, like a silent sister beside her.

Published on November 10, 2015