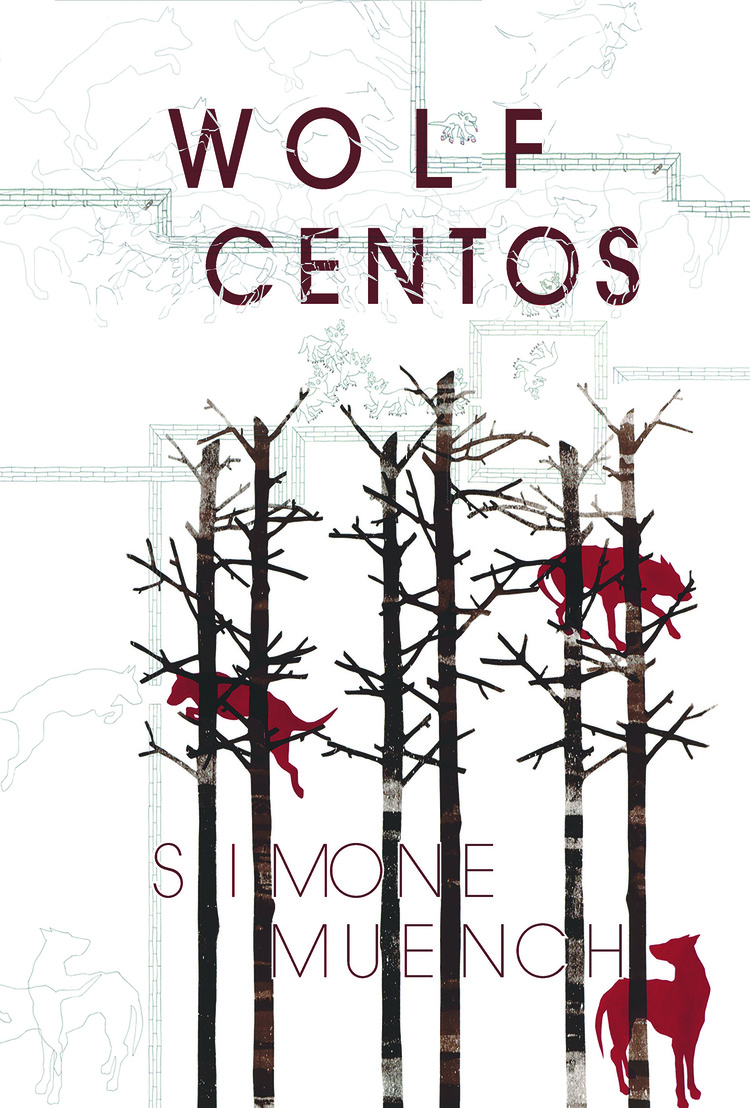

Wolf Centos

by Simone Muench

reviewed by Julie Swarstad Johnson

Few forms demand such submission from writers as do centos, a purely collaged form with a millennium and a half of history. Unsurprisingly, centos appear only rarely in contemporary poetry. Wolf Centos, Simone Muench’s fifth collection of poetry published by Sarabande Books, approaches the challenge of centos through absolute commitment—Muench can’t claim to have written a single word of Wolf Centos’ sixty pages. And yet every word becomes hers; the one hundred and eighty-seven source poets listed at the back of the book remain secondary to Muench’s project. In Wolf Centos, Muench presents a daring attempt to submit to formal constraints and create something lasting within them.

Muench, a professor of creative writing and film studies, titles each poem in the collection “Wolf Cento,” continually signaling that while the lines are borrowed, the poems are original acts of curation and arrangement. The title also draws attention to wolves or the wolf, here an enigmatic figure. “We wanted to be wolves,” Muench writes in “[We: spectators, always, everywhere],” “strange animal with its miraculous elusiveness— / a step toward luck & a step toward ruin.” Muench’s wolf has the allure of a fairytale villain, a danger standing in for something else. The collection’s opening poem concludes:

I have stood for a long time

at the edge of a river, unknown, nameless,

hands groping for the shape of the animal.

Not knowing what all the music had been hiding.

(“[I saw my life a wolf loping along the road]”)

The wolf, a menace both enticing and real, Muench tells us, has been just out of sight all along.

Muench constructs her centos from nearly two hundred sources, including Anne Carson and Marianne Moore, Dino Campana and Tomas Tranströmer, Anna Akhmatova and Gwendolyn Brooks. From Wisława Szymborska’s “Reality Demands” (translated by Stanisław Barańczak and Clare Cavanagh), Muench takes the line, “This terrifying world is not devoid of charms.” Szymborska’s poem encompasses the globe as it grapples with destruction and the truth that “life goes on.” Muench, however, uses the line in a poem that lingers closer to home, narrowing Szymborska’s worldview to a single speaker’s intimate experience of her own life:

This terrifying

world is not devoid of charms—

the poppy that no girl’s finger has opened,farmhouses dark against a sublime blue,

an airplane whistling from the other world.

(“[Who will take the madness from the trees?]”)

Throughout Wolf Centos, Muench employs potentially familiar lines but asks us to reconsider them in a new context. “I will name nothingness / the lightning which bore you,” she borrows from Yves Bonnefoy as translated by Galway Kinnell (“[A stranger’s coming past]”). She continues in the voice of Muriel Rukeyser: “I am working out / the vocabulary of my silence,” putting the poets in conversation with one another on the page.

Whether you know many or none of the lines culled to create Wolf Centos, Muench gives them new life. Readers familiar with Muench’s work will recognize her distinctive voice, simultaneously direct and surreal. “Hex,” from her 2010 collection Orange Crush, could easily fit into Wolf Centos, with its bizarre list of “poke root and bladderwrack, / chalklines in bloody bedrooms / and black reptilian bags.” A similar list of images piles up in “[There is a wolf in me, sound]”: “sound / of countries, red cassia flowers, / inheritance of gallows; something / in the mouth like feathers.” Even when collaging, Muench gravitates toward a diction and images all her own. We could consider this a defect: Muench dedicates herself to collaging and creates something that doesn’t sound remarkably different from her other work. Or we could call it accomplishment: from fragments, Muench creates a cohesive whole consistent with her own style.

Centos offer us two main avenues of assessment—do we appreciate them for their sources and for the effective use of those sources, or do we value their success as new poems regardless of their origins? To focus on either choice leaves something vital out of the equation. In Wolf Centos, Muench gathers a wide array of voices into dreamlike poems that circle through a dark world of snow and blood, trees and closed doors, wolves and women. “Which of us is writing this page I don’t know,” Muench quotes Jose Luis Borges as translated by Norman Thomas di Giovanni (“[You hear things. I see them.]”). Wolf Centos presents an attention-worthy engagement with a demanding form.

Published on April 12, 2015