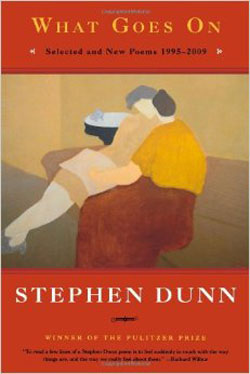

What Goes On

by Stephen Dunn

reviewed by Chard deNiord

Stephen Dunn, the winner of the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, has taken on ambitious subjects—God, the death of God, the fallen world, what men want, history, salvation, beauty, language, the afterlife—with bravado throughout his career. Although this volume contains selected poems from Dunn’s last six books, including Loosestrife (1996), Riffs and Reciprocities (1998), Different Hours (2000), Local Visitations (2003), The Insistence of Beauty (2004), and Everything Else in the World (2006), along with twenty new poems, What Goes On reads almost seamlessly as a continuous book. Dunn writes one poetic commentary after another, claiming that “despite appearances, / I haven’t said a word.” At the same time, he maintains that writing serves as a critical act of verification: “I think I’ll keep on describing things / to insure that they really happened.”

Dunn employs a heuristic speaker who mines personal experience for self-knowledge. The things he learns in his poems, things he didn’t know he knew, serve as poetic consolations to what Simone Weil called “life’s impossibility.” In a signature strategy that combines philosophical rumination with lyrical narrative and commentary, Dunn addresses his epistemological muse directly:

It was then that Sisyphus realized

that the gods must be gone, that his wings

were nothing more than a perception

of their absence.He dared to raise his fist to the sky.

Nothing, gloriously, happened.

While Dunn often succeeds in undermining his philosophical gravitas with refreshing candor and self-reflexive wit, as in “Salvation,” “The Answers,” “Best,” “The Living,” and “Please Understand,” he also occasionally conjures epiphanies with an overly familiar ring. Consider the rejoinder at the conclusion of “Talk to God”: “But let it be known you’re willing to suffer / only in proportion to your errors, / not one unfair moment more.” Such advice resonates as naive, especially in light of the horrors of twenty-first-century strife. But Dunn’s poems depend less on acknowledging the complexity of the postmodern world than on audacious musing about proverbial, philosophical, and mythological subjects. As many of Dunn’s “religious” poems suggest, old saws and recycled complaints are simply part of a poetic mix that also contains jokes, defiant energy, and new stories about old subjects in an atheist’s lifelong agon with nihilism.

Yet Dunn makes no claims to be anything other than what he is, one of New Jersey’s metaphysicians. He aspires to write in a demotic, candid, epiphanic style, creating a poetic vernacular for his unabashedly philosophical subjects. And he is a deeply American poet as well, in his loyalty to his private muse, reflecting the highly individualistic, self-reliant “man-thinking” that Emerson championed in his landmark essay, “The American Scholar.”

In their broad range of subject matter and emotions, the poems in What Goes On comprise an admirable body of work, alternating between humorous and serious expression. His musing is most profound in his more economical and lyrical poems, captured perhaps most poignantly in his poem “Zero Hour” from his Pulitzer Prize‑winning book Different Hours. In confronting nothingness itself, Dunn confesses his own sense of futility as a poet, as well as his love for spontaneity in free verse.

It was the hour of simply nothing,

not a single desire in my western heart,

and no ancient system

of breathing and postures,

no big idea justifying what I felt.I wanted to feel something, but it was nothing more than a moment

passing into another, or was it even less

eloquent than that, purely muscular,

some meaningless twitch?I’d let someone else make it rhyme.

Although one might wish for a more engaged contemporary voice that makes new arguments for atheism or the mere vanity of life, Dunn’s best poems in What Goes On testify to the self-effacing strength of the lyric’s ability to bear the burden of Western weight.

Published on March 6, 2015