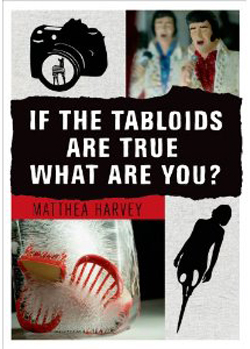

If the Tabloids Are True What Are You?

by Matthea Harvey

reviewed by Rachel Trousdale

Some books feel familiar. Even if you can’t see around the next corner, you can predict when the next surprise is due. The number of pages in your right hand tells you more or less what to expect in the way of resolutions to the problems posed by the pages in your left. These books can be pleasant and reassuring to read, but you probably don’t remember them very vividly three weeks after you’ve finished. Then there are books like Matthea Harvey’s If the Tabloids Are True What Are You?

This is a book of surprises. That is not to say that it is erratic or that it darts off on tangents. On the contrary, it is meticulous, coherent, consistent. But the rich, delightful world Harvey (author of four other books of poems and two children’s books, and winner of the 2009 Kingsley Tufts award) establishes in these poems is just sufficiently at variance with the familiar to keep the reader slightly puzzled and off balance. Tabloids leaves you looking at well-known objects and finding them rewardingly peculiar.

If the Tabloids Are True What Are You? combines poetry, paper cutouts, and photographs into a series of mutually resonant narratives. Elements echo between the sections—there are a lot of mermaids; bonsai trees grow here and there; electricity is a theme; as the collection progresses we get accruing hints of melting polar ice caps—but each section can stand alone, with its own formal constraints and internal story arc.

From the opening series of prose poems about mermaids—“The Straightforward Mermaid,” “The Homemade Mermaid,” “The Deadbeat Mermaid,” each facing a black silhouette of a woman’s torso attached to a tool instead of a fish tail—to the final “Telettrofono”—a polyvocal narrative of the life of the Italian inventor Antonio Meucci, who came up with the telephone before Alexander Graham Bell—the book has the same kind of magical coherence and internal variety as a good collection of fairy tales.

Along the way we encounter, among other oddities, an erasure of Ray Bradbury’s R is for Rocket; a series with tabloid-inspired headlines like “Cheap Cloning Process Lets You Have Your Own Little Elvis”; “Inside the Glass Factory,” a narrative poem in which trapped girl workers create a new girl out of glass and follow her to an equivocal escape; and “Stay,” a series of photographs of miniature objects (tiny red chairs, figurines) frozen in melting blocks of ice. Each set of poems has its own artwork: “Telettrofono” is paired with illustrations of Meucci’s inventions embroidered on canvas, “Inside the Glass Factory” with photos of slender, colored glass bottles.

If the Tabloids Are True What Are You? is a book about connection across a long distance. This theme is most visible in “Telettrofono,” in which Meucci’s invention is motivated by his love for his wife Esterre, whom Harvey imagines as a mermaid who has come to land for the pleasures of airborne sound. But the same electrical spark appears in “The Tired Mermaid” and the marvelous “My Owl Other.” The import of large-scale interconnections among distant places is essential to the slowly building disasters of melting ice and flooding cities in the book’s central sections.

At the same time, the tabloid poems stage startling combinations of middle-class America and metaphysical playfulness. As “Using a Hula Hoop Can Get You Abducted By Aliens” (which first appeared in Harvard Review) explains, aliens (who coin their own nouns) believe that while “the Leash-holders who take their Furries / to the park three point five times per day” are too self-contained to be of interest and “belong with [their] Far-bits / on the ground,” “the dreamy ones,” the artists and hula-hoop users, unwittingly signal their desire “to go somewhere they don’t know / how to get to.”

Somewhere, someone reading this review is expressing skepticism. “Oh good,” that person is saying, “a poet in Brooklyn who writes about mermaids and takes photographs of model chairs frozen in ice. How quirky. I bet the chairs are all locally sourced. Are any of the poems about kale?” But the fact that it is not difficult to imagine reading this book in hipster Brooklyn is trivial. What is important is how the book’s whimsical leaps are integral to its unified and serious vision of how everyday objects are implicated both in the sublime and the catastrophic.

For example, erasures can be gimmicky, but Harvey’s Bradbury erasure, “M is for Martian,” weaves together several of the collection’s dominant threads. In sentences like “I heard / the / Martian / hissing / in / slow motion, / it / moved / like / a / hundred years of dreaming,” the poem showcases Harvey’s commitment to combining lyrical language with natural speech. It demonstrates that her love of the fantastic is rooted in a profoundly humane interest in how human emotions are continuous across unfamiliar settings. By showing that this lyricism and this humanity are both already present in Bradbury’s text, Harvey roots her distinctive work in a collaborative process with other artists—a process also visible in “Telettrofono,” which was created from the biographies of real people and with the collaboration of the sound artist Justin Bennett. And by presenting the erasure literally—as photographs of pages of the original book modified with white-out—Harvey makes a case for reading image and text as, if not a seamless whole, at least one which has been beautifully sewn together.

Published on December 2, 2014