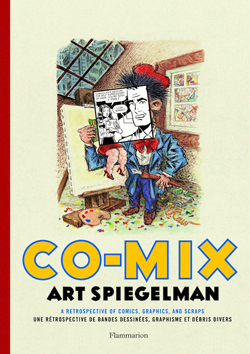

Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps

by Art Spiegelman

reviewed by Paul Hanna

An impressive and thorough catalogue of materials displayed at the 2013 Art Spiegelman retrospective exhibit at the Jewish Museum in New York, Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps is essentially the biography of Spiegelman’s work itself. Spanning his entire career, from his earliest 1960s fanzine work to a 2012 stained-glass window for his high school alma mater, even touching on the 2013 preparation of the very exhibit documented by the book, Co-Mix is a densely packed recording of the creative output of a cartoonist, author, editor, illustrator, artist, and advocate for the medium he started in—comics.

What makes Co-Mix especially attractive is its collection of sketches, roughs, studies, and other material illustrating the working process behind the artist’s work. Spiegelman is known for the simple, scrawly visual style he developed specifically for the seminal Maus, but these supplemental pieces offer insight into the painstaking deliberation involved in creating something that intentionally looks simple, minimal, and easy to visually digest. Co-Mix reveals much of the process behind Maus, showing early versions of pages, notebook excerpts that break down the story, and numerous sketches and studies of the same individual page, even the same individual panel. “In the time that other artists can draw forty pages, I can draw one page forty times,” Spiegelman writes.

Equally intriguing is a single page featuring twenty different drafts of a 1994 New Yorker cover illustrating the ribbon-wrapped legs of a runway model in action. Small yet important differences among the covers cast light on Spiegelman’s sensibility. Working analog as Spiegelman did, each cover image was recreated from scratch, and while all these repetitions may offer insight into the artist’s neurotic behavior, they also remove some illusions about the creative process.

For readers who know Spiegelman primarily from his work in Raw magazine and Maus, there is a substantial body of work prior to and surrounding the publication of these signature comics. While Spiegelman did not produce the final paintings, the first series of Wacky Packages cards and stickers, created for Topps, are in large part conceptually designed by him. The Wacky Packages series, parodying various consumer products, from “Crust” toothpaste to “Ajerx” cleanser, were hugely popular in the 1960s and 1970s, along with their distant relative, “Garbage Pail Kids,” co-created by Spiegelman in the 1980s. According to Spiegelman, “In some ways Wacky Packages and Garbage Pail Kids—the two most successful projects I was involved with—were an extension of my underground comix work. It was all a part of the counterculture . . . but some of it took place at the candy counter.”

Another thing that becomes apparent is how heavily the work of Harvey Kurtzman—most notably, the first twenty-eight issues of Mad magazine (all edited by Kurtzman)—influenced Spiegelman. As an editor and writer, Kurtzman brought a unifying aesthetic to the EC Comics of the 1950s. While Mad magazine was obviously rife with Kurtzman’s trademark gag humor, his war comics, Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat, were caustically bitter. Kurtzman’s great range of work informed both the prolific R. Crumb in the 1960s and 1970s and Art Spiegelman in the 1970s and 1980s. In his short story, “A Furshlugginer Genius!,” which is set in Kurtzman’s art class at the School of Visual Arts, Spiegelman describes how revolutionary his mentor was to the medium.

According to Spiegelman, the main idea behind Mad’s satire—that “the mass media is lying to you . . . including this comic book!”—directly influenced much of Spiegelman’s work. Not only does this sentiment represent the height of popular iconoclasm, it is the perfect perch of vitriolic irreverence and paralyzing self-deprecation. Being the scrupulous messenger in an institution that erodes the trust of its audience is still being part of the institution. Spiegelman’s work lives and thrives on this self-awareness. Despite the myriad ways that Spiegelman deconstructs popular culture and society, most of his creations have been consumed in the same commercial way.

Published on July 8, 2014