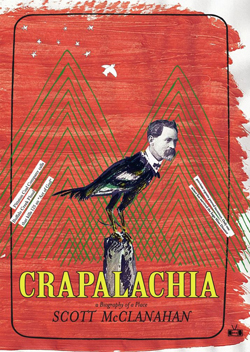

Crapalachia

by Scott McClanahan

reviewed by Amanda Peery

It’s impressive how much Scott McClanahan can write without a using a single metaphor. He refuses to craft elegant paragraphs or lyrical descriptions. He just likes a good story. His writing is easy to underestimate because he skips over anything that bores him, but McClanahan has a big range and a lot of skill. He writes all the weird, sad, and funny facts of his life with complete emotional honesty.

McClanahan has a huge supply of true(ish) stories set in the Appalachian hollers. He has already written six books and Crapalachia was one of two published last year. In Crapalachia, he deals with death and grief, and the result is some of his best and deepest writing. The book is described as a novel, but it is written as a series of fast-paced anecdotes and feels more like a cross between a book of short stories and a memoir (the appendix points out the few instances of exaggeration and embellishment—the rest, we’re supposed to believe, is true).

It all begins with McClanahan flipping through an old photo album, giving snapshots of his family, like:

My dad was working at Kroger . . . [and one day] the manager was saying the names of these guys who broke into the store and stole a bunch of shit.

He said the name of one of the robbers: “Stanley McClanahan.” Then he asked my dad, not thinking. “Do you know him, Mack?”

My dad said: “Yeah, he’s my brother.”

So the room grew quiet and the manager later apologized to him.

This is typical McClanahan—entertaining but also sad. He goes from this to a story about the attempted exorcism of his schizophrenic uncle. Then he asks about the number of people in a family photo and learns that five of his aunts and uncles killed themselves.

Story after story about death and mental illness come out in a rush until McClanahan yells, “BUT STOP!” He does not want to stop because of the overwhelming darkness of the memories, he wants the stories to go by more slowly. He wants to resurrect dead relatives through their stories, and he wants to hold onto them for as long as possible. McClanahan even asks for his readers’ help: in a chapter called “You Can’t Put Your Arms Around a Recipe,” he includes a recipe for his grandmother’s fried chicken. “If you’re reading this,” he writes, “you can try making it right now . . . and we can bring these zombies back to life again.”

One of the most interesting things about McClanahan as a writer is his belief that he has a real relationship with you, the reader. He talks to you as though you were sitting in the room with him. He wants to tell you about his life, about life in general, and, above all, he wants to tell you the truth. This can mean talking about the disgusting parts of life—here the book’s title serves as a warning. There are gall-bladder stones, smelly feeding tubes, “steaming piles of dog shit,” even the most heartbreaking scenes in the book are revolting. In one of these, McClanahan’s uncle, who has cerebral palsy, loses control of his bowels. The teenage McClanahan tries to hold his uncle’s limp body upright while cleaning up the excrement in a public bathroom.

McClanahan could have blamed a lot of the dirtiness, discomfort, and misery of his early life on the place where he grew up, but instead he takes backwoods West Virginia on its own terms. Crapalachia is subtitled “A Biography of a Place,” and McClanahan collects his memories, shared family history, and local legend in order to try to better understand his home. In part this is a way of resisting the clichés about Appalachia and the idealization implicit in art. He thinks about “people from Ohio” who buy scrap quilts like the ones his grandmother makes and is angry about their glorification of poor, rural America. “The quilt wasn’t a fucking symbol of anything,” he writes. “It was something she made to keep her children warm. Remember that. Fuck symbols.”

Published on May 22, 2014