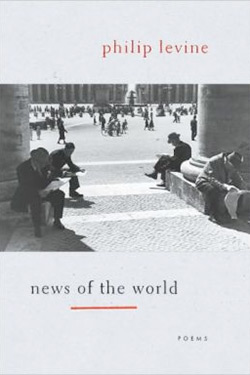

News of the World

by Philip Levine

reviewed by Chard deNiord

For nearly sixty years, Philip Levine has been praising the famous men and women of the Detroit auto industry, as well as a wide range of unsung others, including relatives, jazz musicians, adolescent lovers, moguls, fellow poets, martyrs, and schoolmates. While Levine’s lucid, declarative voice resonates throughout all twenty of his books of poetry, agreeing at every turn with Emily Dickinson’s claim that “Drama’s Vitallest Expression is the Common Day / That arise and set about Us,” his compassion leads him repeatedly to identify both tenderly and self-effacingly with others. Few other poets of his generation, with the exception of James Wright, have woven lyrical expression into demotic narratives with a comparably deft hand and persevering vision of the downtrodden and disenfranchised.

In his new book, News of the World, Levine complements this strategy with metaphysical intimations. By frequently invoking silence at the end of his poems, Levine continues to report everyday news, while also intoning intimations of the ineffable.

If he came

To my door now on his trek

To nowhere I’d welcome him back

With black wine and black bread,

A glass of tea, a hard wood floor

To sleep on, and hope the new day

Brought him the music of silence.

(from “Yakov”)

… the sea taught you

and you taught me:

the sea goes out

and nothing comes back.

(from “My Fathers, The Baltics”)

Now you say this is home,

so go ahead, worship the mountains as they dissolve in dust,

wait on the wind, catch a scent of salt, call it life.

(from “Our Valley”)

As in his previous nineteen books, Levine leads his reader in News of the World through the purlieus and hubs of his old haunts—Detroit, Manhattan, Havana, Barcelona, Lisbon, Philadelphia, and Dearborn, showing and telling the news of ordinary men and women, such as the Cuban lieutenant’s blind devotion to Hemingway in “The White City,” or the husband’s ironic happiness in prison in “Not Worth The Wait.” In addition to his mostly short-lined verse poems, Levine includes a fascinating eight-page section of prose poems. While less lyrical than his verse poems, they facilitate a more straightforward reportage of his poetic news. With little irritable reaching after his subjects and a limpid verse style, Levine allows simple, memorable truths to emerge naturally from his poetic storytelling. He has honed his narrative expression, employing speakers who keep an objective distance from both themselves and their subjects. Such distance makes for a kind of double accounting in which Levine’s witness becomes a fascinating combination of no-nonsense observer and incisive commentator.

In this latest book, which Levine claims took a long time to cohere, he takes a bold new step in addressing the mystery of his voice head-on. In his remarkable poem “Two Voices,” he concludes with this apostrophe to an unspecified other who could easily be his reader:

Let’s say I phone you tonight and tell you

my little adventure which came to nothing.

What will you think? Not what will you say,

you’ll say it was an illusion or you’ll say

there was a deep need in me to hear

that particular voice, or sometimes the voices

of the air—all the separate voices in so

public a place—can unite for a moment

to produce “Philip” or “John” or “Robert”

or whatever we expect. I don’t know

what you’ll think. I’ve never known, even

when you and I were together, and I’d

waken in the false dawn to hear you

in the secret voice that was yours crying

out into the dark a name not mine.

It’s in just this self-effacement and unknowing that Levine ironically finds what he earlier in the poem refers to as the disembodied “huge voice, deep and resonant”—the same voice that humbles itself before the “the music of silence” and, in so doing, discovers what Wallace Stevens called “the voice that is great within us.”

Published on March 18, 2013