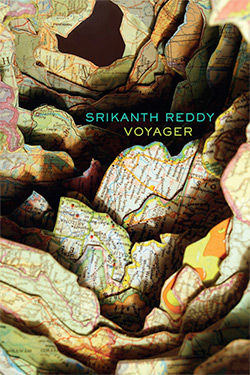

Voyager

by Srikanth Reddy

reviewed by Broc Rossell

After reading Werner Heisenberg’s lectures, John Lukacs wrote to George Kennan that “The very purpose of historical knowledge is not so much accuracy as a certain kind of understanding: historical knowledge is the knowledge of human beings about other human beings.” This sense of history, in which we seek to apprehend not objective data but an aspect of human development through the cumulative uses of a subject or story, is one subject of Srikanth Reddy’s second collection of poetry.

Voyager is a sequence of erasures of Kurt Waldheim’s 1985 memoir In the Eye of the Storm, known for its complete omission of his early career as an intelligence officer in Nazi Germany’s Wehrmacht (the agency which housed the Waffen-SS) before serving two terms as secretary-general of the United Nations from 1972 to 1981. Waldheim’s tract is tedious, pusillanimous political boilerplate. To write it Waldheim lied, at the very least to himself.

By erasing the lie, as it were, fitting himself inside this hole and working his way out (while, incredibly, retaining the order of words), Reddy voices both white-hot outrage and intense compassion. For in declaring that “Kurt Waldheim is a negotiation,” and repurposing his memoir to describe the process of a professor writing a book, Reddy reveals levels of engagement that resemble something like the modern human condition:

To cross scenes out of a text would not be to reject the whole text. Rather, to cross out a figure such as to carry out programmes they approve the various regional economic commissions and inter governmental bodies sometimes increases the implications. I had hoped to voice my unhappiness with the world thus. More and more, it seems to me the role of the Secretary General in this book is that of an alter ego. In a nightmare, Under Secretaries General, Assistant Secretaries General, and other officials of rank reported directly to me. I was given an office and a globe. But I wondered why the forest just beyond the window seemed so cold when it was, to be sure, rapidly burning.

Moments like this (and there are many), when Reddy and Waldheim seem as tightly joined as Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, lend meditations on diverse subjects a profound resonance. By refashioning Waldheim’s ghastly prose into sequences of theorem, memoir, and allegory to create a sum far greater than its parts, Reddy has shared the responsibility of Waldheim’s failures with everyone who reads his book. He elegantly merges concepts of shared identity with shared responsibility thus: “The failed idea repeatedly described in this book is alter ego.”

Architectural in structure and epic in scope, Voyager is a monument divided into three books, with a last section entitled “Epilogues.” Because Reddy uses Waldheim’s Chapter 8 (“The New Majority”) as source material for each book, certain words, phrases, and lines reappear and echo as reiterations. It is an unnerving experience to see moments such as “The dead do not cease in the grave” and “The world is water falling on a stone” reappear in entirely different contexts. These repetitions slowly amplify, evolving from instances of sound and cadence into moments of psychological and, ultimately, philosophical significance; by emphasizing the contextual nature of language, Reddy demonstrates its capacity both to mediate and to multiply shared experience.

Voyager begins:

The world is the world.

To deny it is to break with reason.

Nevertheless it would be reasonable to question the affair.

Instantly aphoristic, with the cultural authority of familiar music, Book One alone is enough to secure a poetic reputation. What Reddy characterizes in his note as a “sequence of propositions” merges the emotional, philosophical, and historical as transparently as poetry, with all its cadence and nuance, can manage.

Book Two, which contains sixteen prose blocks like the one above, is a challenge to read in Waldheim’s voice, so convincingly does it offer a simulacrum of authorial voice. Written in a recognizably contemporary lyrical “I”—Anne Carson’s Nox and Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely produce the same terrifying calm with this smallest word —Book Two recounts seemingly private thoughts in relation to an orbiting subject.

Book Three is a colossal eighty-page sequence, subdivided into eighteen chapters and one “Epilogue” and written in the descending staircase of William Carlos Williams’s stepped triadic line. The “I” of this sequence is the persona of Waldheim recounting an imagined life, a false narrative that serves as an allegory of a politician’s soul: expansive, self-justifying, enamored of regalia, and a reminder of the frailty of honest leadership. At its core is an italicized sequence, invoked by Hamlet’s anxiety of action as a “play within the play,” in which the lacunae are preserved, and the words dance on the page as elegantly and tragically as an arpeggio of the subconscious.

In Voyager’s final act, dark black text from the source material is presented for the first time in faint, struck-through gray ink. Reddy’s selections triumphantly and compassionately merge with the original text, magnifying the enormity of the preceding white space and begging the question of how much distance separates our imagined reality from the one we share.

Voyager is an indication of what is possible in the form. For its remarkable innovation, panoramic lyricism, and utter empathy, it may well endure.

Published on March 18, 2013